Plus de Lumière: The Illuminating Spirituality of Lee Bae’s Charred Cosmos

Words by Eric David

Location

Saint-Paul-de-Vence, France

Plus de Lumière: The Illuminating Spirituality of Lee Bae’s Charred Cosmos

Words by Eric David

Saint-Paul-de-Vence, France

Saint-Paul-de-Vence, France

Location

The Maeght Foundation presents Plus de lumière, an expansive exhibition of Paris-based, Korean artist Lee Bae whose work for more than two decades now has centred on the evocative use of charcoal. Curated by art critic Henri-François Debailleux and featuring paintings, sculptures and installations, the latter specifically designed for the Foundation’s gallery spaces, the show traces Bae’s constantly evolving relationship with his materia prima whose profound blackness is poetically expressed through a language of abstract forms that he has been exploring since the early 1990s.

Located among pine trees on a hill just outside Saint Paul de Vence in southern France, the Maeght Foundation is a haven of 20th century European art, boasting a permanent collection that is one of the largest in the world and a purpose-built venue that features treasures such as the Giacometti courtyard, Miró's labyrinth, Braque's pool and mural mosaics by Marc Chagall and Pierre Tal-Coat. Displaying Bae’s work in such a Modernist Mecca may seem odd, but on the contrary, the purity and spirituality of his work, which draws from the canon of Western abstract art such as Arte Povera and Abstract Expressionism, as well as from traditional artistic practices from his home country, are perfectly aligned with the venue’s monastery-like ambience. In fact, the building’s upturned roof structures and pine-wood setting serendipitously resemble the architecture and context of Korean temples, something which hasn't been lost on the artist and which makes the staging of his exhibition here even more pertinent.

Issu du feu, 1998. Carved charcoal, 30 cm in diameter. Installation view at the Daegu Art Museum in 2014. Photo © PARK Myung-Rae. / © Lee Bae.

Lee Bae, Plus de lumière. Exhibition view at Fondation Maeght. Photo by Roland Michaud.

Landscape. Burnt tree trunks, 18 x 16 m. Installation view at the Daegu Art Museum in 2014. Photo © PARK Myung-Rae. / © Lee Bae.

Landscape. Burnt tree trunks, 18 x 16 m (detail). Installation view at the Daegu Art Museum in 2014. Photo © PARK Myung-Rae. / © Lee Bae.

Issu du feu (detail), 2000. Charcoal trunks attached by elastic threads. © Lee Bae.

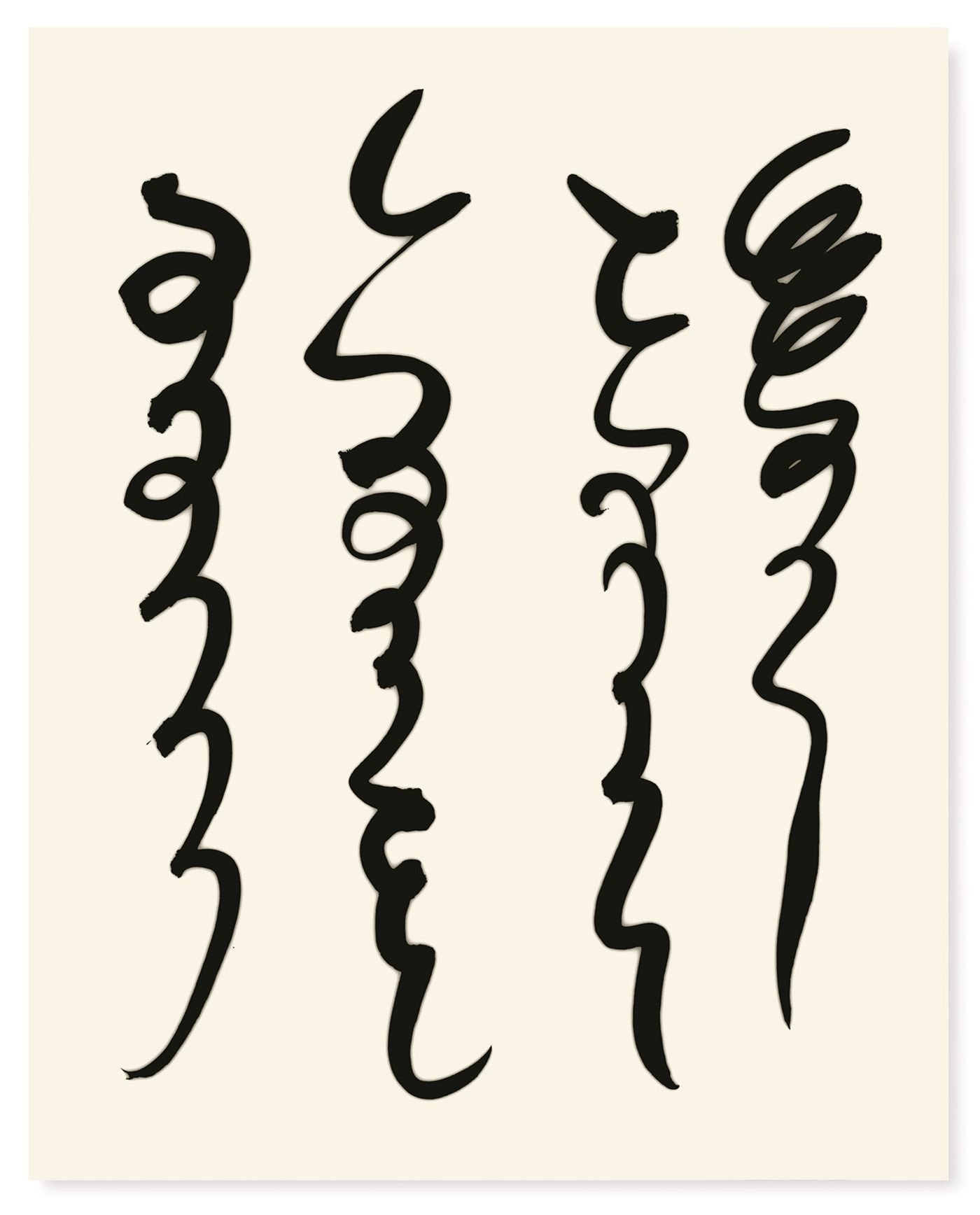

Bae started using charcoal when he moved to Paris in 1990 and was looking for an inexpensive material to work with. He was soon captivated by its hybrid nature, dense and porous when in solid form, light and ethereal when it becomes dust. The cultural connection of the material to his home country also proved to be important, for not only does charcoal allude to India ink and the art of calligraphy, it also holds a special place, both traditionally and symbolically, in Korean culture. This connection is lyrically captured by a video that welcomes visitors to the exhibition introducing them to the concept of Moon House Burning, the traditional Korean ritual of setting a house-like mound of pine trunks on fire on the first full moon of the lunar year thereby reducing the past to ashes and allowing a new day to be born. Written on pieces of paper and attached to these Moon Houses, people's wishes are said to be carried all the way up to the moon.

© Lee Bae.

From the fire, 2001. Burnt wood stakes gathered, 370 x 156 x 80 cm. Installation view at the Daegu Art Museum in 2014. Photo © PARK Myung-Rae. / © Lee Bae.

Issu du feu, 2000. Charcoal and elastic thread, variable measures. Installation view at the Daegu Art Museum in 2014. Photo © PARK Myung-Rae. / © Lee Bae.

Issu du feu, 2000. Charcoal on canvas, 210 x 440 cm. Installation view at the Daegu Art Museum in 2014. Photo © PARK Myung-Rae. / © Lee Bae.

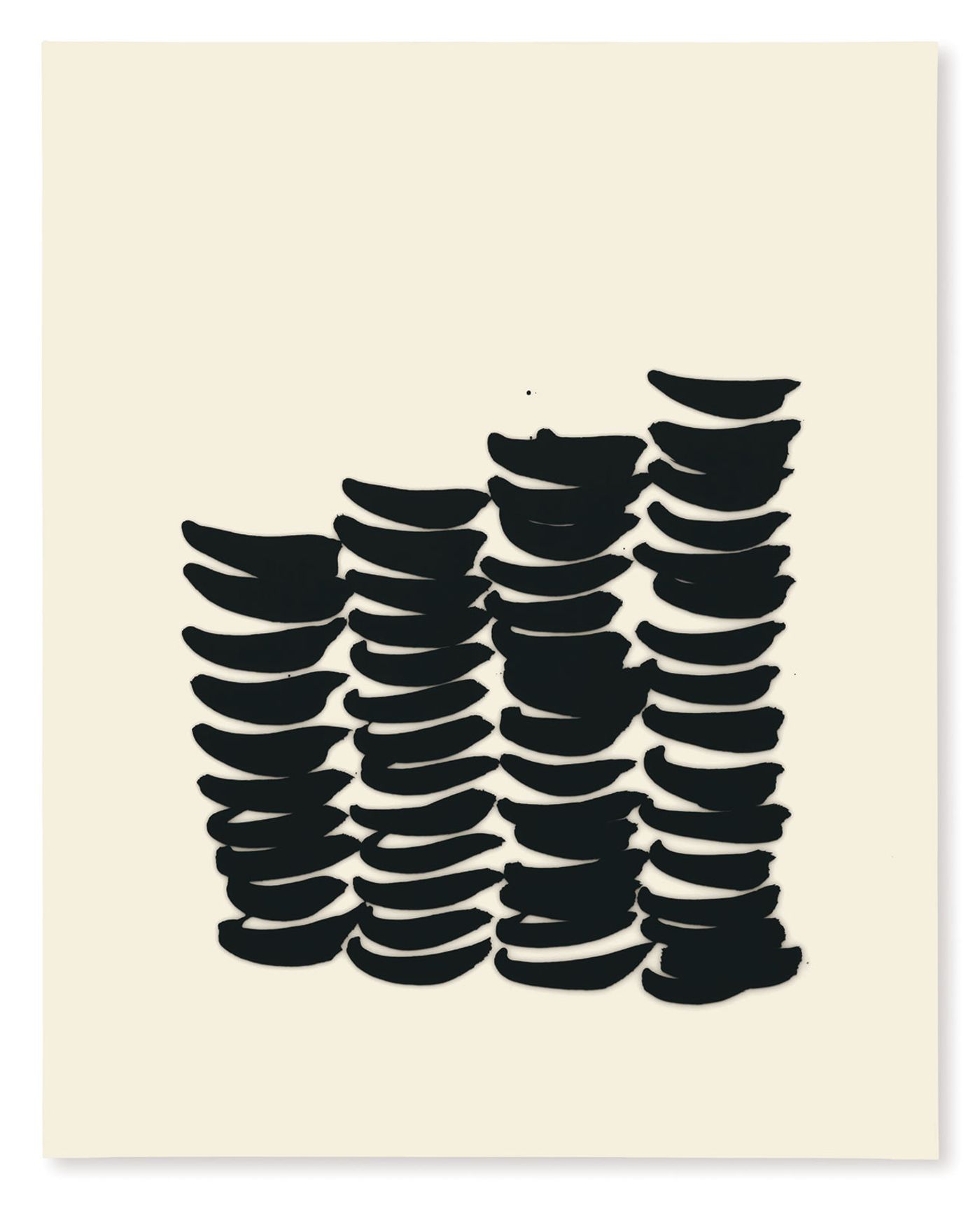

Untitled, 2012. Acrylic medium, charcoal on canvas, 116 x 89 cm each. Installation view at the Daegu Art Museum in 2014. Photo © PARK Myung-Rae. / © Lee Bae.

Lee Bae, Plus de lumière. Exhibition view at Fondation Maeght. Photo by Roland Michaud.

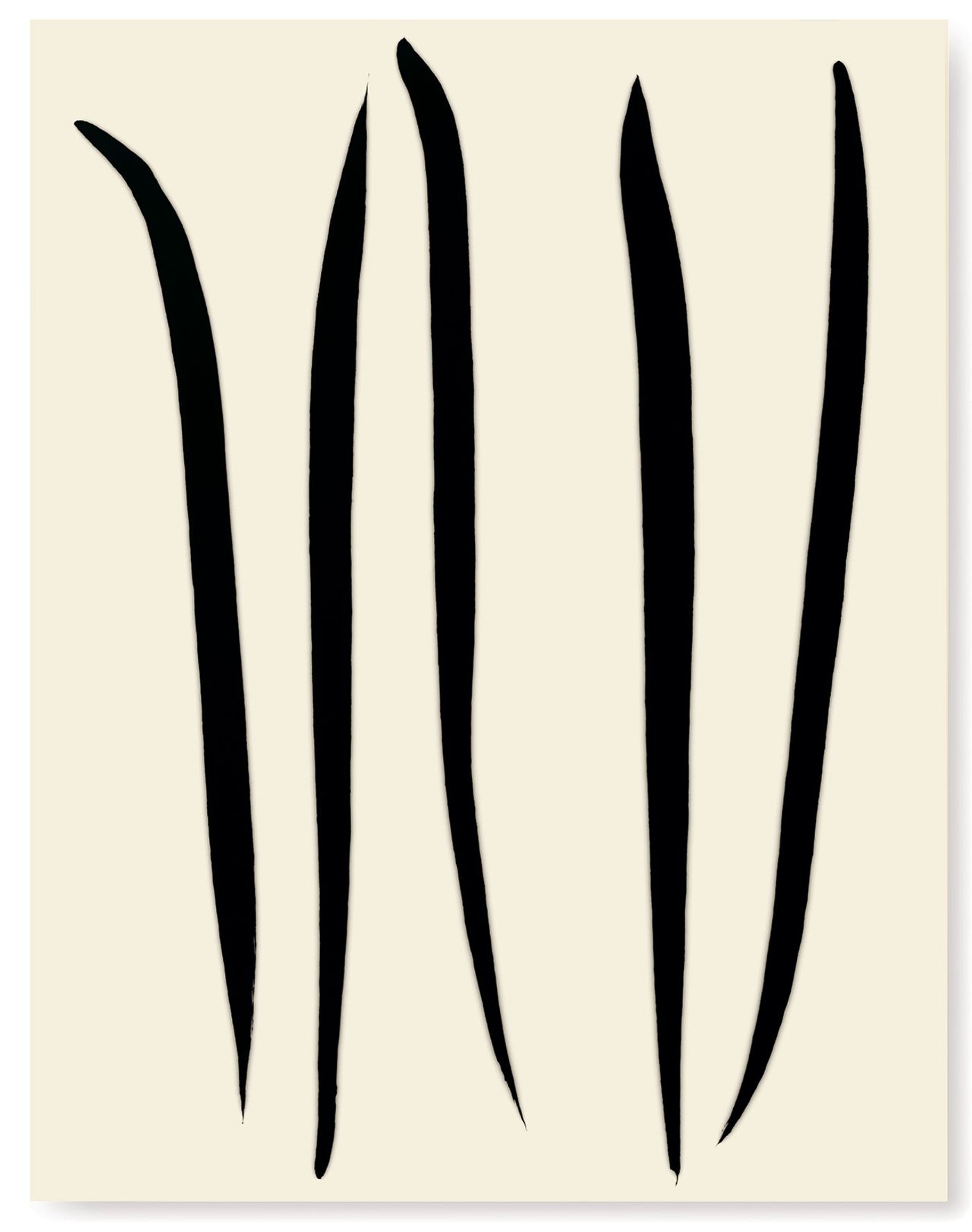

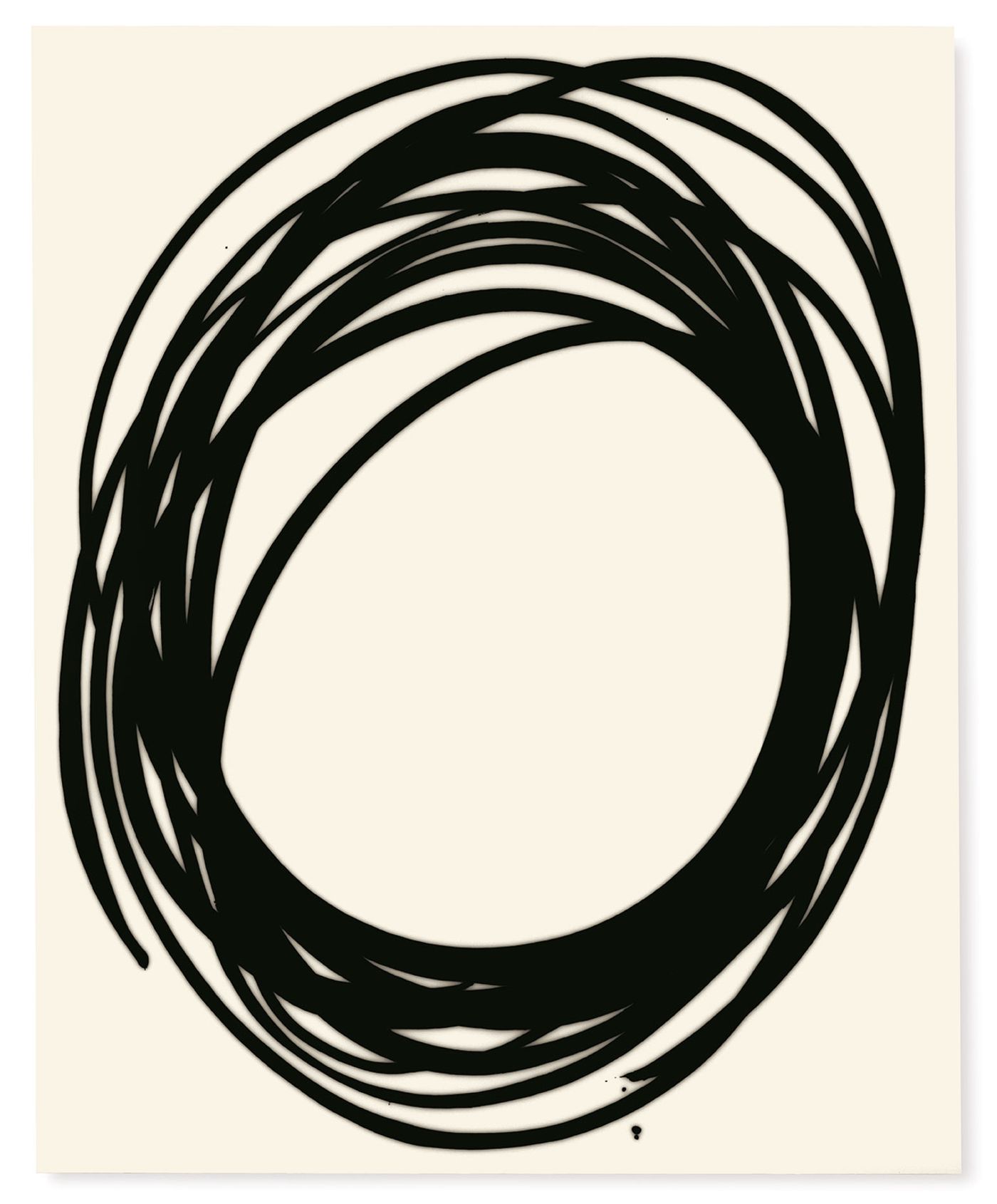

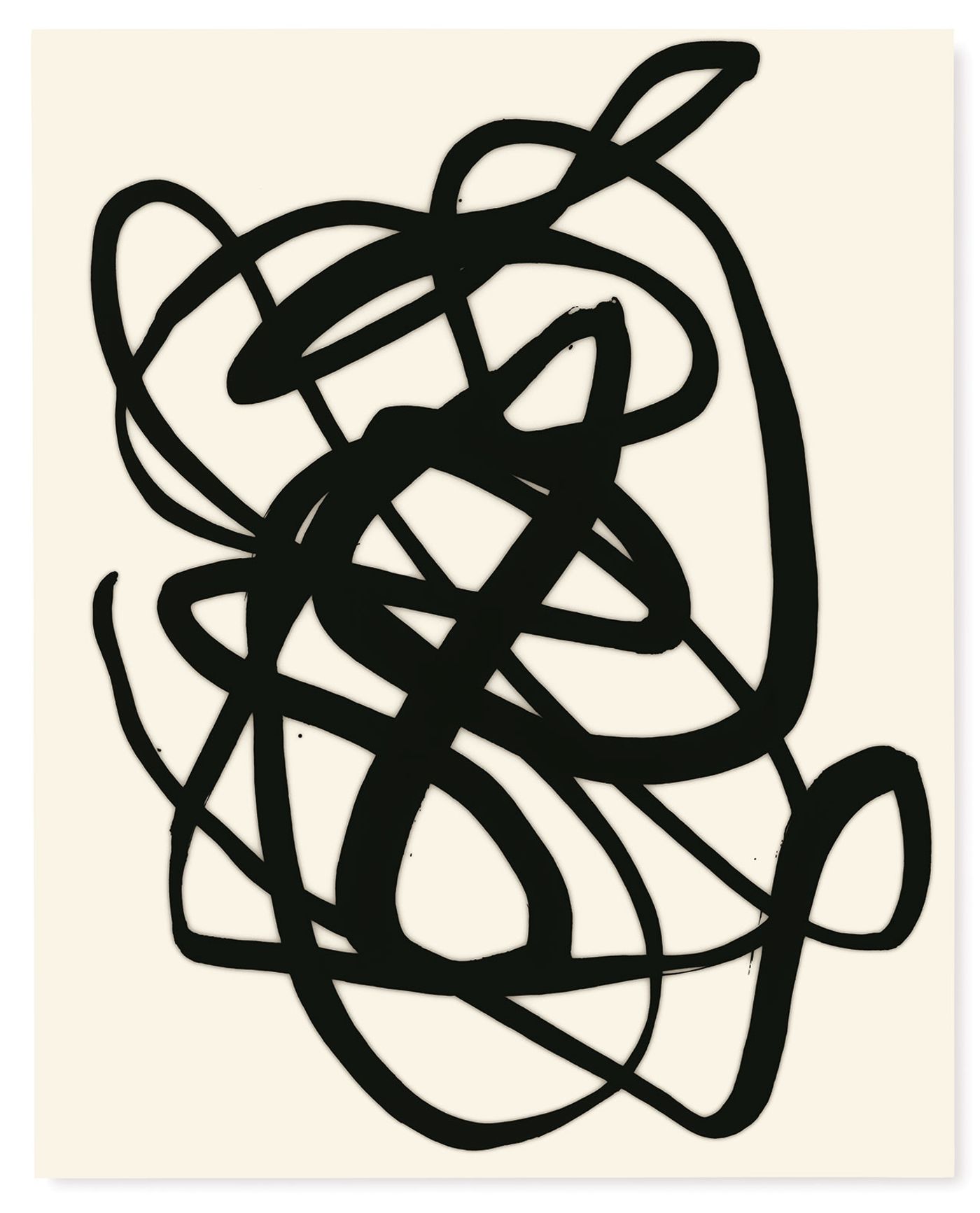

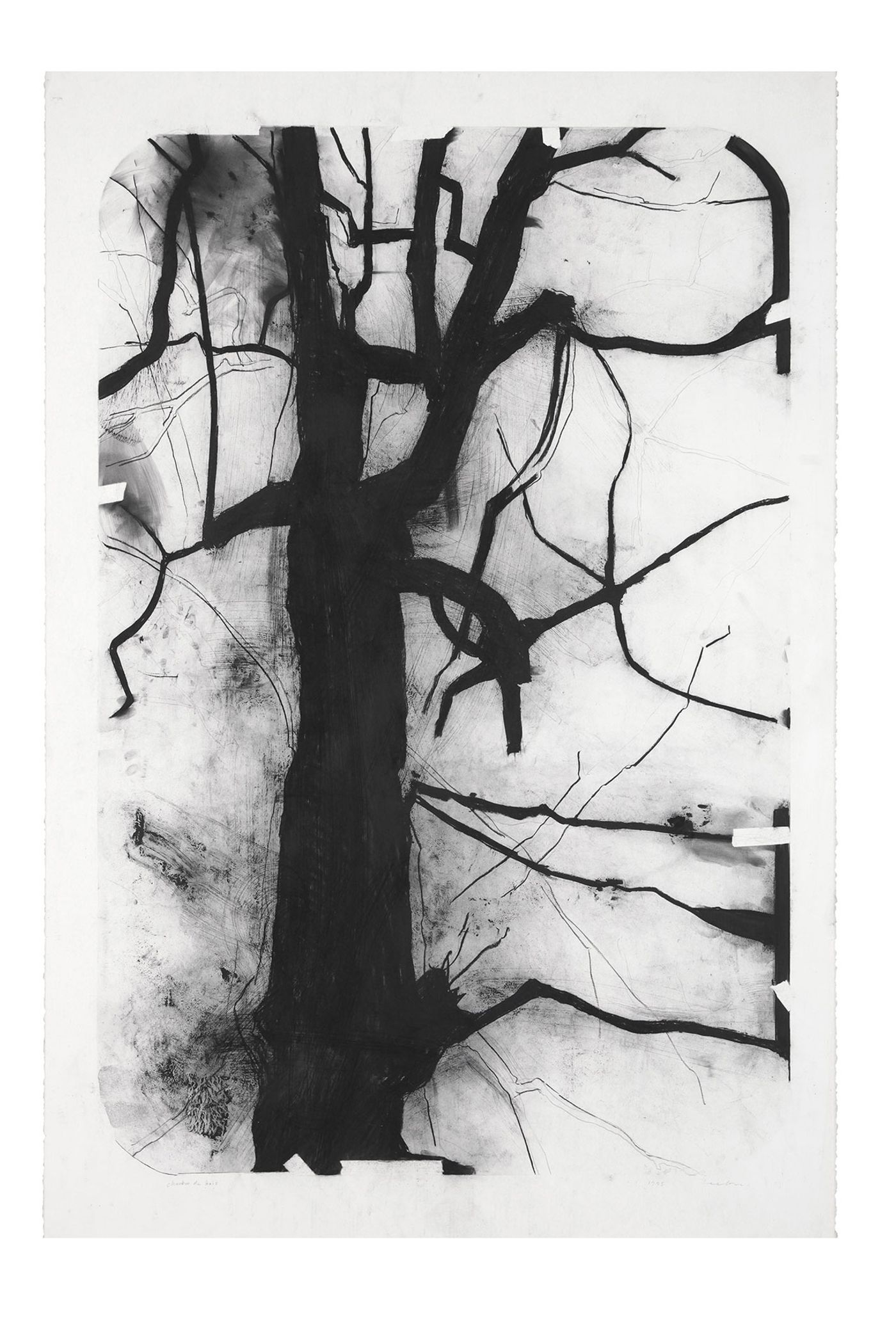

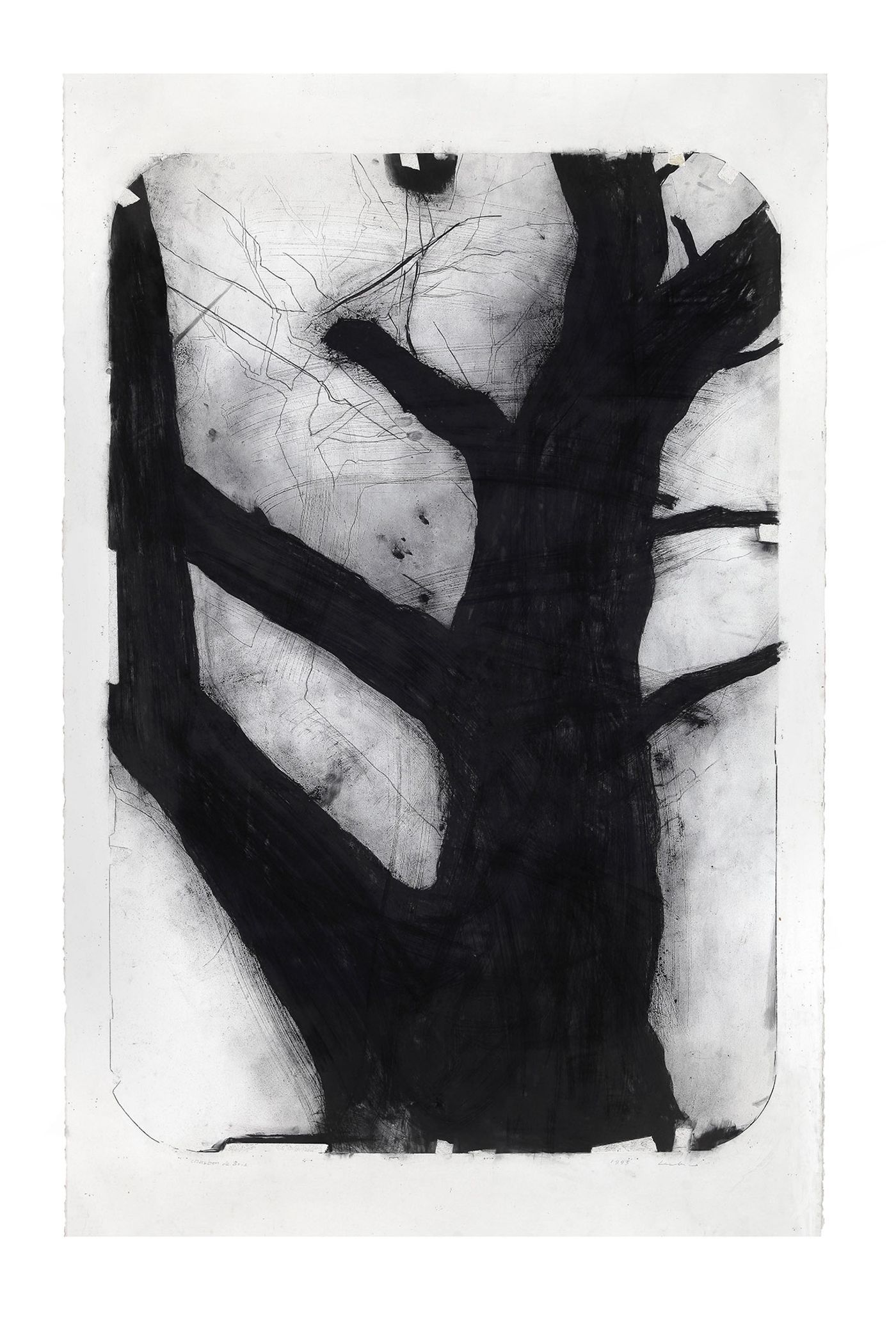

Although at first glance, Bae’s latest paintings, Untitled, seem to have been made in a frenzy of spontaneous gestures, they are in fact the fruit of a laborious and time-consuming process that takes one to two months. Beginning with a series of ink drawings where he experiments with forms and shapes, the selected imagery is then redrawn countless times in order to ensure, as the artist eloquently says, that “the hand that has fully memorised the score" before the actual painting is precisely and ritualistically created though a choreography of graceful movements. Fixed with multiple, superimposed layers of semi-transparent acrylic medium which the charcoal is soaked into or rubbed on, Bae’s waxed-like canvases acquire an unexpected sense of depth, oscillating between light and shadow, transparency and opacity, buoyancy and heftiness.

Lee Bae, Plus de lumière. Exhibition view at Fondation Maeght. Photo by Roland Michaud.

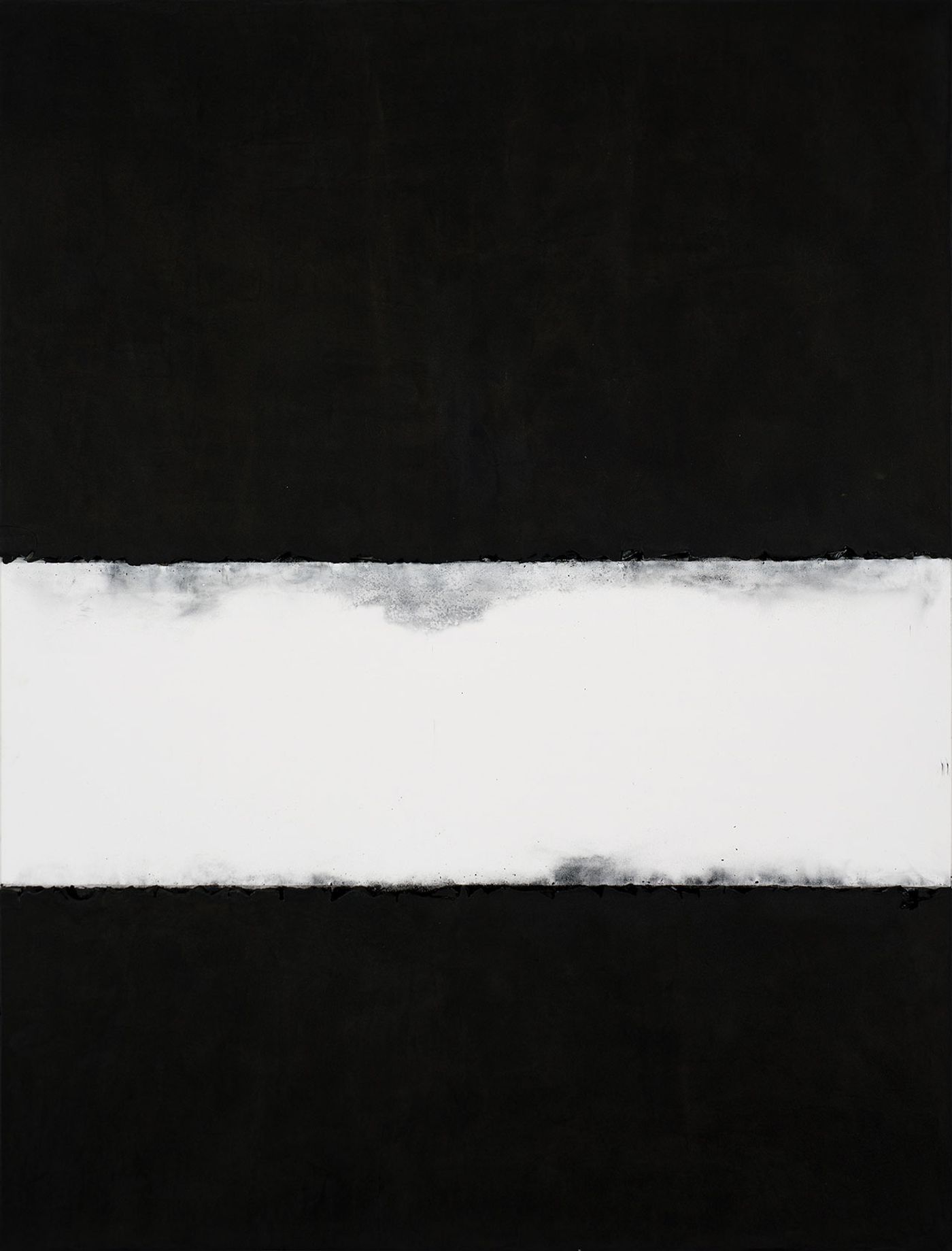

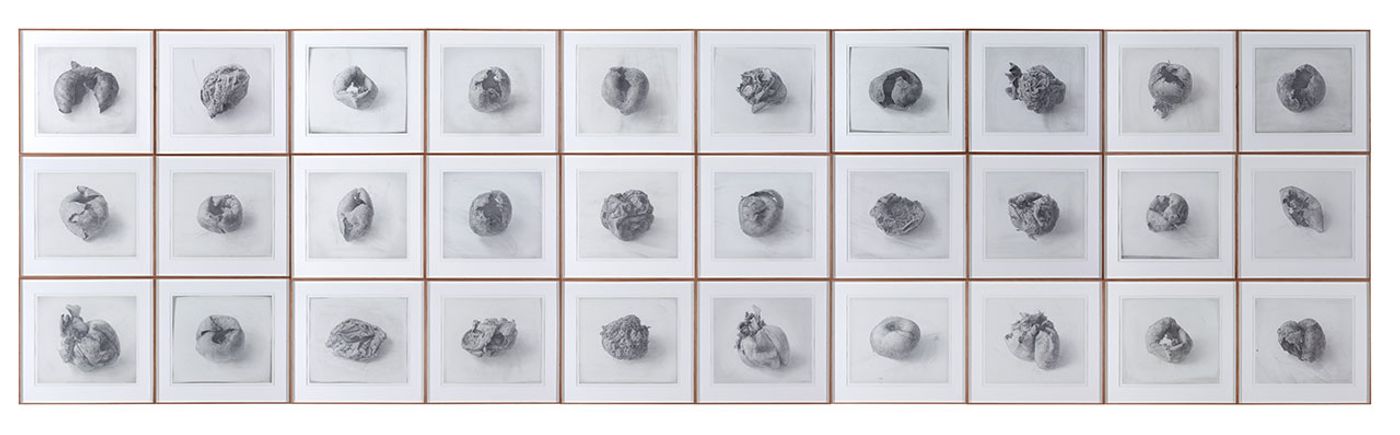

Bae is an artist who above all else likes to experiment and this ethos is exemplified in a variety of pictorial styles and methods represented by his work on display. Landscape, a series of paintings from the late 1990s and early 2000s for example, feature abstract, black on white, geometric shapes made out of charcoal powder thickly caked unto the canvas, which are juxtaposed with his Dried Persimmon series from the same period where Bae has drawn in great detail the fruit’s drying process, the decaying sensation made all the more evocative by sprinkling persimmon vinegar to produce yellow stains. Meanwhile, other, larger, all-black canvases that refract light in various directions and in multiple angles loom like glittering mosaics.

Cheong Do. Dried Persimmon. (40 pieces), 2000. Graphite on paper, 51 x 54 cm each. © Lee Bae.

Lee Bae, Plus de lumière. Exhibition view at Fondation Maeght. Photo by Roland Michaud.

Lee Bae, Plus de lumière. Exhibition view at Fondation Maeght. Photo by Roland Michaud.

Lee Bae, Plus de lumière. Exhibition view at Fondation Maeght. Photo by Roland Michaud.

In the building’s pine garden, Bae has installed eight large bundles of charred logs, exclusively made of pine and tied together with black rubber bands, which look like otherworldly menhirs, similar to the prehistoric stones that stand in Carnac in Brittany, France. Carbonized in South Korea near Bae’s birthplace where they burnt for two weeks at a temperature of about a thousand degrees and were then left to cool down for another two, the charcoal clusters sit among the pine trees of Saint Paul de Vance as a poetic encounter between the two countries’ conifer species as well as a symbolic token the artist’s regular trips back and forth between France and South Korea. Stripped off their naturalistic attributes down to their bare soul, the charred logs are not unlike Giacometti's sculptures next door.

Issu du feu (detail), 2000. Charcoal trunks attached by elastic threads. © Lee Bae.

Issu du feu, 2000. Charcoal trunks attached by elastic threads. © Lee Bae.

Lee Bae, Plus de lumière. Exhibition view at Fondation Maeght. Photo by Roland Michaud.

Similar charcoal compositions, grouped under the same title, Issu du Feu, are exhibited inside the gallery spaces along with other installations such a 16 by 14 meters area covered in charred logs, a dystopic yet mesmerizing topography from Bae’s Landscape series, and a block of perfectly aligned wooden stakes, also from the same series, whose charred, smooth top and unburnt, multipronged base coexist in jarring tension. The overwhelming physicality of these works is a reminder, as the artist points out, of man’s ability to radically transform such a natural material, turning wood to charcoal through fire, but also of charcoal’s pre-eminence among the material world, “when everything else has gone, the purity of its matter remains”.

Viewed all together, Bae’s evolving use of charcoal reveals an infinite field of expression but also points to an inherent yet pivotal incongruity at the heart of his work, a creative process whereby something effectively dead—charcoal is after all the final state of all organic matter—is used to bring something else to life, namely his artistic vision.

Lee Bae, Plus de lumière. Exhibition view at Fondation Maeght. Photo by Roland Michaud.

Lee Bae, Plus de lumière. Exhibition view at Fondation Maeght. Photo by Roland Michaud.

Lee Bae, Plus de lumière. Exhibition view at Fondation Maeght. Photo by Roland Michaud.

Lee Bae in his studio. Paris in 2016. Photo © KIM Mia. / © Lee Bae.