Reclaiming the Pyramid of Tirana: MVRDV Transforms Albania’s Most Controversial Monument

Words by Yatzer

Location

Tirana, Albania

Reclaiming the Pyramid of Tirana: MVRDV Transforms Albania’s Most Controversial Monument

Words by Yatzer

Tirana, Albania

Tirana, Albania

Location

There are two ways of dealing with relics reminiscent of tyranny: tear them down, or change them to make them something else entirely. Although the latter approach has the advantage of sustainability and adaptive reuse, can it truly reconcile a dark past with hope for the future? The rebirth of the Pyramid of Tirana, once the absurdly lavish shrine to Albania’s longtime dictator Enver Hoxha, triumphantly confirms that it can. MVRDV, the Dutch architects known for their playful, audacious transformations, have turned this brutalist relic of oppression into an effervescent hub for youth, creativity, and—perhaps most symbolically—free thinking.

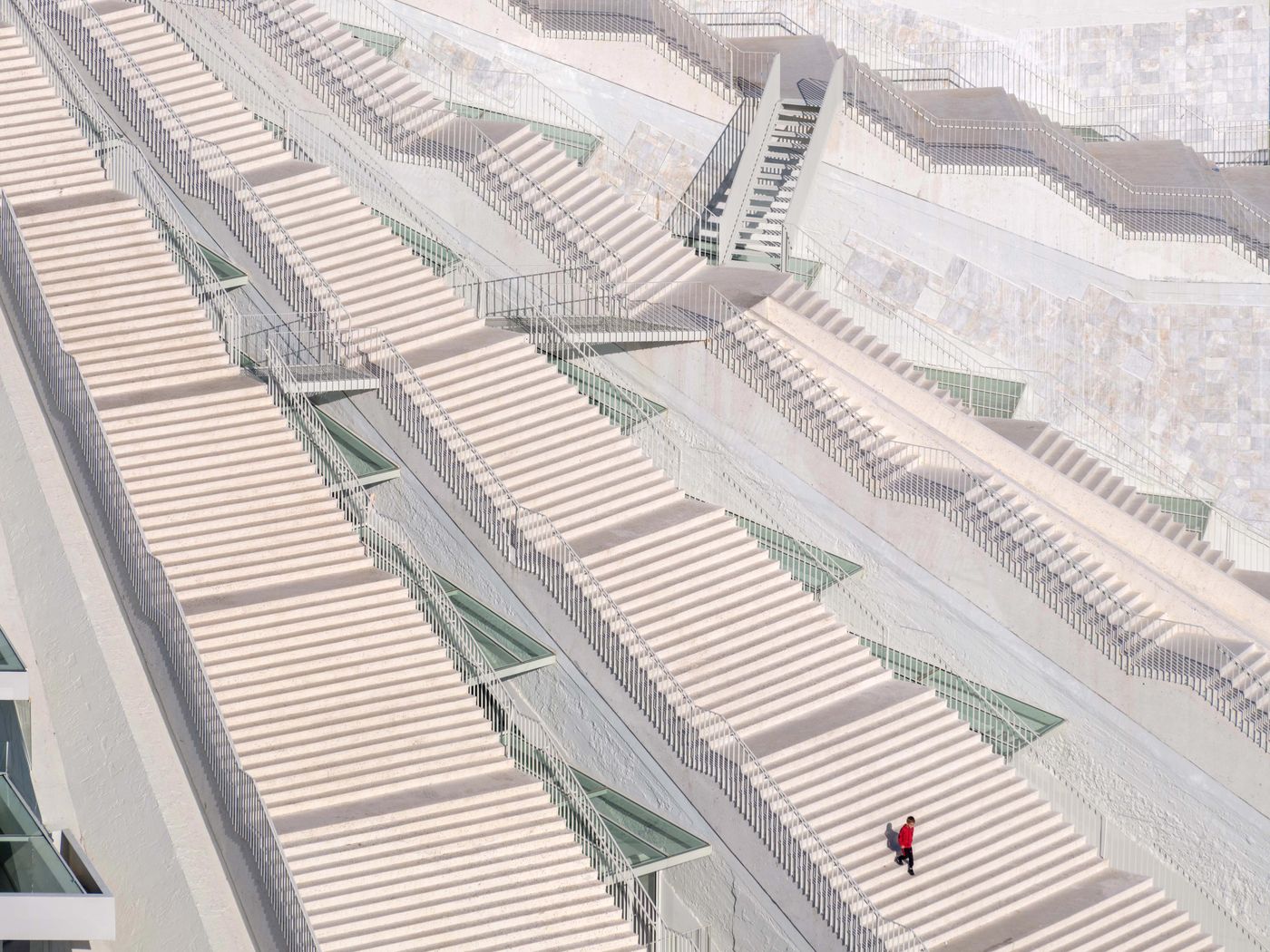

With steps added to the building’s sloping façades, allowing the people of Albania to literally walk all over it, and a constellation of vibrantly coloured boxes scattered in and around the original structure—housing cafés, studios, offices and classrooms where Albania’s youth can learn various technology subjects for free—the Pyramid of Tirana is no longer a mausoleum to a leader long reviled, but rather a living monument to a nation’s ability to reclaim its past.

Photography © Ossip van Duivenbode.

Photography © Ossip van Duivenbode.

From the beginning, the Pyramid was a curious object. Completed in 1988, just a year before the collapse of communism in Albania, it was a hybrid of science fiction and pharaoh worship—part brutalist bunker, part dystopian dreamscape. It was the most expensive building ever commissioned by the communist regime, at a time when most Albanians lived in dire poverty. It was meant to glorify a leader who had banned colour televisions and Coca-Cola, yet its form looked more at home in a Kubrick film than in socialist realism. Ironically Hoxha’s reign of iron was over almost as soon as the Pyramid opened its doors. The dictator’s museum quickly lost its purpose, and in the decades that followed, the structure became a strange, contradictory presence in Tirana’s skyline to later become a radio station, a nightclub, a conference hall, a NATO base during the Kosovo War, and perhaps most importantly, a symbol of uncertainty over what to do with the past.

The answer, it turns out, was hidden in plain sight. Over the years, Tirana’s youth had turned the Pyramid into an impromptu playground. Climbing up its sloping concrete beams and sliding down became a rite of passage, a rebellious re-appropriation of a space that once loomed with oppression. MVRDV’s genius was not in inventing something new, but in amplifying this spirit. The transformation maintains the bones of the structure but makes it porous, vibrant, and alive. The most striking addition? Steps allowing people of all ages to walk up the very surfaces that had once been too treacherous to scale officially.

Photography © Ossip van Duivenbode.

Photography © Ossip van Duivenbode.

Photography © Ossip van Duivenbode.

Photography © Ossip van Duivenbode.

Photography © Ossip van Duivenbode.

Photography © Ossip van Duivenbode.

Photography © Ossip van Duivenbode.

Photography © Ossip van Duivenbode.

Scattered in, on, and around the existing structure are brightly hued, box-like volumes, housing everything from cafés and start-up incubators to workshops and classrooms. Many of these spaces belong to TUMO Tirana, a non-profit educational institution offering free courses in software development, robotics, animation, music, and film to 12- to 18-year-olds. In a country where access to such resources has long been limited, the transformation of a dictator’s shrine into a free technology school for the next generation is as poetic as it is pragmatic. The other half of the spaces are open to the public, functioning as rental spaces for businesses, cultural programs, and creative labs. Running the entire colour gamut, the ensemble of multicoloured volumes defies the drab severity of the Pyramid’s past, signalling a new chapter while subtly satirizing Hoxha’s ban on colour television.

For all its exuberance however, MVRDV’s design does not erase the past. The scars remain—cracked marble, exposed beams, and stripped-away cladding serve as a reminder of the building’s origins. This delicate balance between preservation and reinvention is what makes the Pyramid’s rebirth so compelling. Neither a sanitized heritage project nor an act of demolition, it is an architectural act of resilience.

Photography © Ossip van Duivenbode.

Photography © Ossip van Duivenbode.

Photography © Ossip van Duivenbode.

Photography © Ossip van Duivenbode.

Beyond its symbolic weight, the project also speaks to a larger global conversation about sustainability, demonstrating that historic brutalist buildings—so often dismissed as obsolete—are in fact ripe for reinvention. Rather than razing the Pyramid and starting anew, MVRDV has embraced circular economy principles, adapting the robust concrete shell to modern needs while minimizing waste. The interior remains largely open, reducing energy consumption by climate-controlling only the added structures.

The Pyramid joins a growing list of contemporary interventions under construction reshaping the city’s skyline, including MVRDV’s Downtown One, a striking mixed-use tower with a pixelated façade, a ‘vertical forest tower’ by Italian architect Stefano Boeri, and two conjoined skyscrapers by Portuguese studio OODA. Bold in design and ambitious in concept, these projects firmly signal Tirana’s ongoing urban renaissance just as much as the country’s evolving identity.

Photography © Ossip van Duivenbode.

Photography © Ossip van Duivenbode.

Photography © Ossip van Duivenbode.

Photography © Ossip van Duivenbode.

Photography © Ossip van Duivenbode.