Title

Lee Bul: Utopia SavedDuration

13 November 2020 to 31 January 2021Venue

Manege Central Exhibition HallOpening Hours

Mon–Fri 11 a.m.–9 p.m., Sat & Sun 10 a.m.–9 p.m.Location

Telephone

+7 812 611 11 00| Detailed Information | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title | Lee Bul: Utopia Saved | Duration | 13 November 2020 to 31 January 2021 | Venue | Manege Central Exhibition Hall |

| Opening Hours | Mon–Fri 11 a.m.–9 p.m., Sat & Sun 10 a.m.–9 p.m. | Location |

1 Saint Isaac's Square Sankt-Peterburg

190000 | Telephone | +7 812 611 11 00 |

Untitled paper #4, 2009.

Acrylic paint, India ink and pigmented ink on paper, 80 x 60 cm. Private collection, Paris

Photo courtesy: the artist

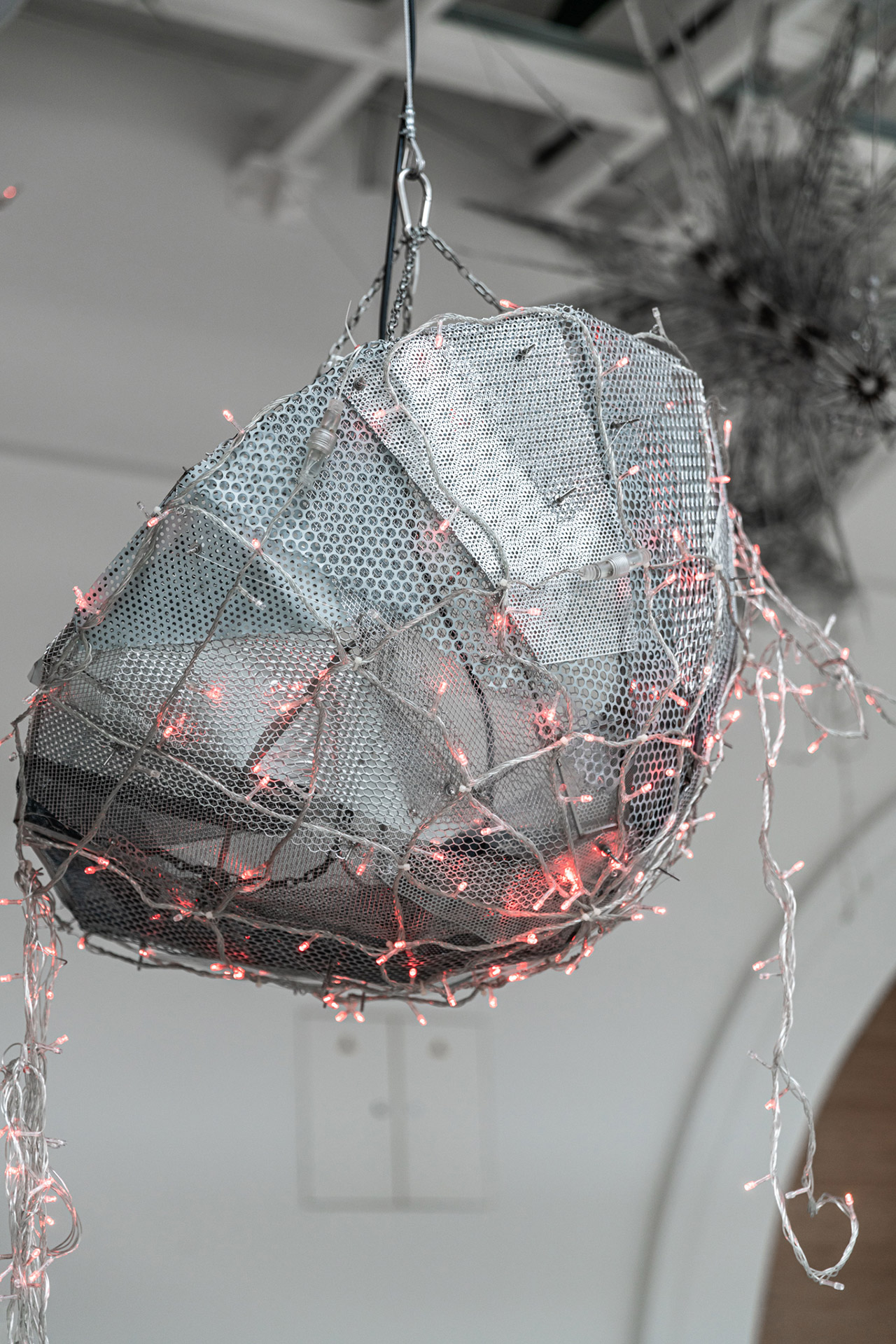

Exhibition view. "Utopia Saved" at the Manege Central Exhibition Hall. Photo by Vasily Bulanov.

Exhibition view. "Utopia Saved" at the Manege Central Exhibition Hall. Photo by Vasily Bulanov.

Exhibition view. "Utopia Saved" at the Manege Central Exhibition Hall. Photo by Vasily Bulanov.

Bul couldn’t have picked a more appropriate venue for her utopia-themed exhibition than the historical Manege. Built in 1807 by Italian architect Giacomo Quarenghi as a riding hall, or manège, for the imperial Horse Guards regiment, the neoclassical building was also used as an exhibition space as early as 1850, introducing the public to the latest in agricultural technology advancements, to later exhibit the works of famous artists of the time. After the revolution the building was used as a warehouse and then as a garage for the Soviet Union’s interior ministry, before finally being turned into a proper art venue in the 1970s. Its turbulent history speaks of society’s utopian aspirations and the socio-political forces that shape them, making it the ideal setting for Bul to unfold her exploration of architectural utopianism and its dystopian consequences.

Exhibition view. "Utopia Saved" at the Manege Central Exhibition Hall. Photo by Vasily Bulanov.

Exhibition view. "Utopia Saved" at the Manege Central Exhibition Hall. Photo by Vasily Bulanov.

Exhibition view. "Utopia Saved" at the Manege Central Exhibition Hall. Photo by Vasily Bulanov.

Exhibition view. "Utopia Saved" at the Manege Central Exhibition Hall. Photo by Vasily Bulanov.

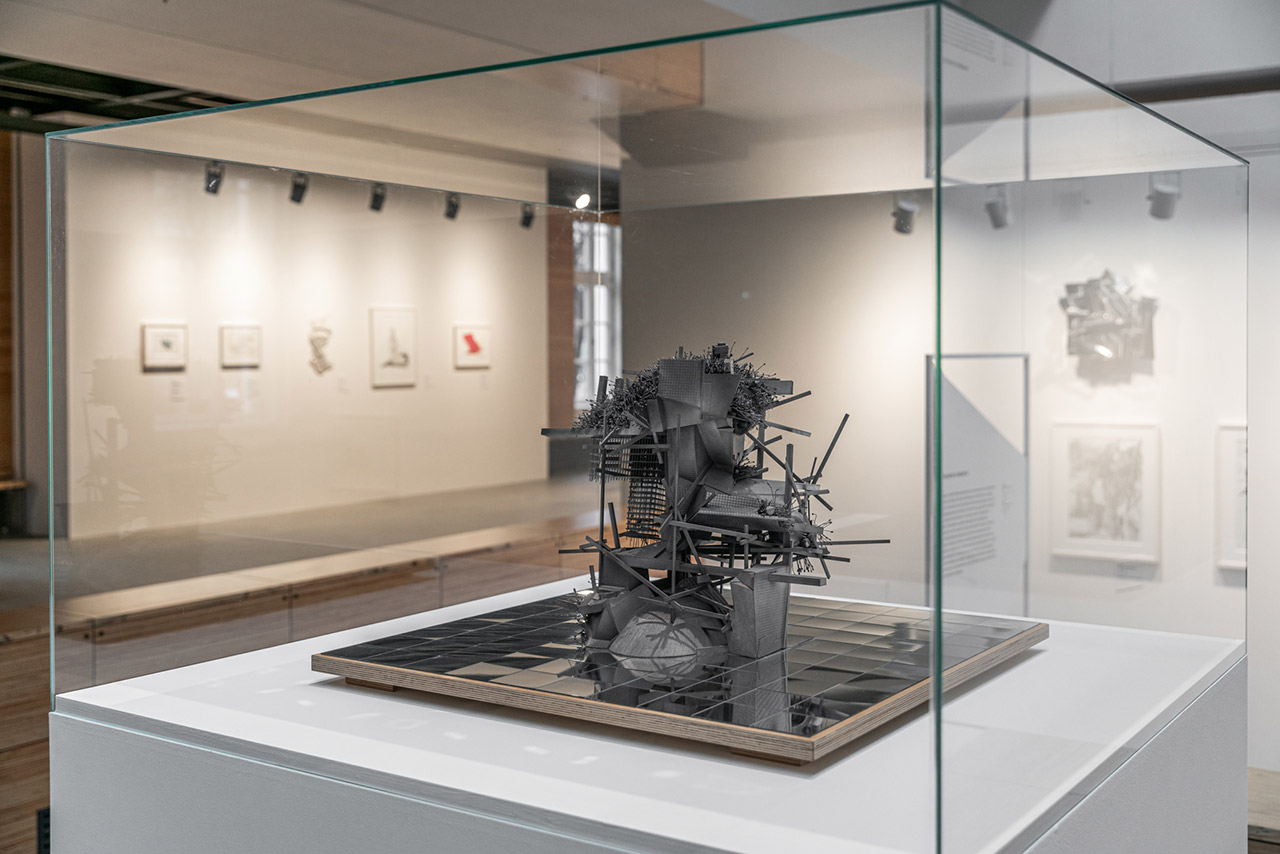

Curated by Sunjung Kim and SooJin Lee, the exhibition was conceived as a journey across a site-specific landscape in close collaboration with the artist who went as far as building a 1:50 scale model of the exhibition space in order to meticulously set out the positioning and configuration of the exhibits. What at first appears as a chaotic melange of installations, sculptures, drawings and photographs is in fact a carefully composed mise-en-scène that also functions as a visual encounter between Bul and the artists, architects and thinkers of the Russian avant-garde who have influenced her work. Opening up unexpected conceptual and visual parallels, the exhibition functions as an overview of the artist’s inquiry into the history of modernity in relation to utopian modernism, as well as picks up on the centuries-old dialogue between the cultures of Russia, Europe and Asia.

Exhibition view. "Utopia Saved" at the Manege Central Exhibition Hall. Photo by Vasily Bulanov.

Exhibition view. "Utopia Saved" at the Manege Central Exhibition Hall. Photo by Vasily Bulanov.

Exhibition view. "Utopia Saved" at the Manege Central Exhibition Hall. Photo by Vasily Bulanov.

Exhibition view. "Utopia Saved" at the Manege Central Exhibition Hall. Photo by Vasily Bulanov.

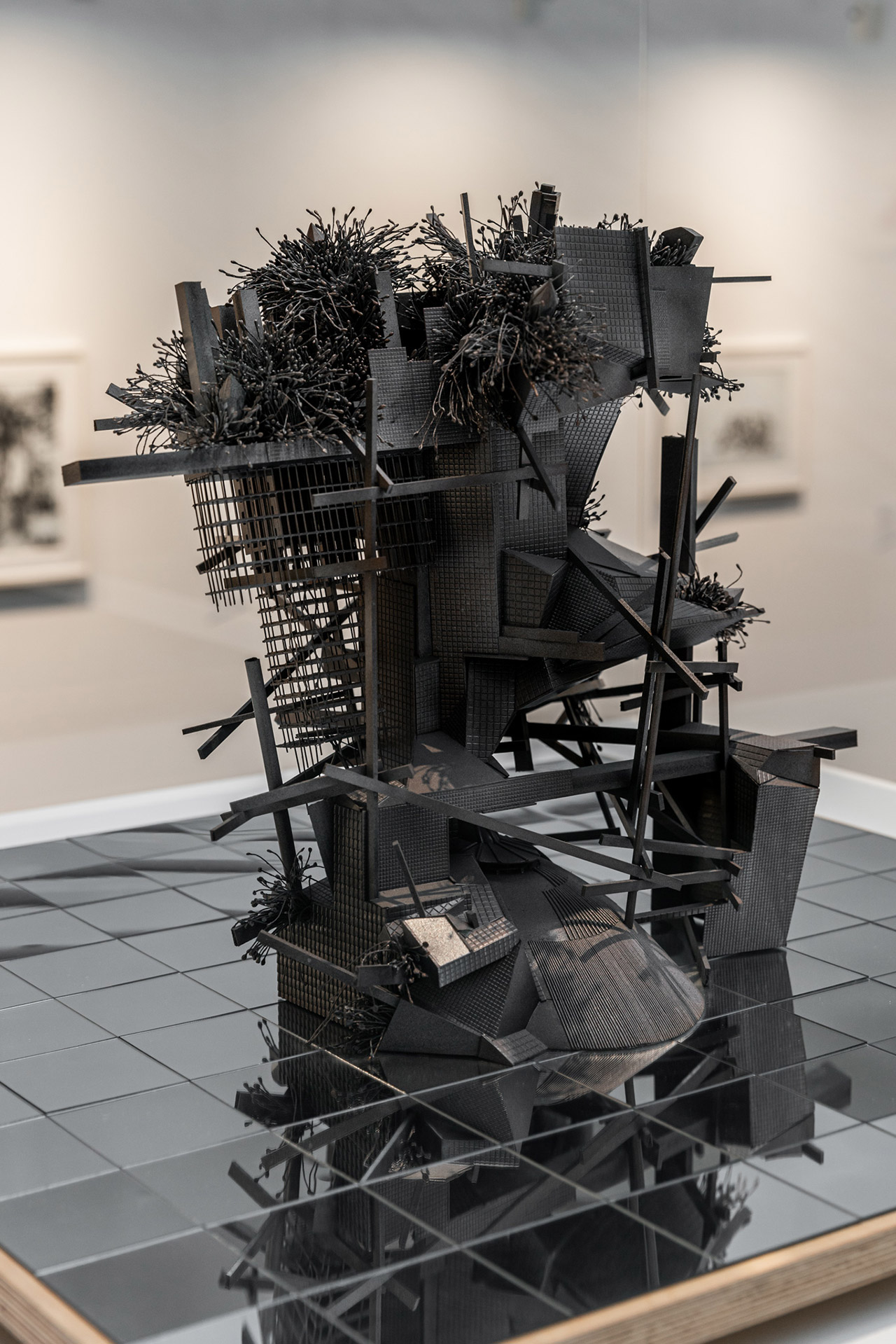

Visitors are introduced to the artist’s inquiry into the dystopic facet of utopian modernism by a maquette of Mon grand récit: Because Everything (2005), an ongoing sculptural series that signalled Bul’s shifted focus to the utopian aspirations of modernist architecture. The piece centres on a jumble of reproduced scale models of iconic modernist structures such as Vladimir Tatlin’s spiralling tower Monument to the Third International (1919–20). The assemblage is surrounded by roller coaster-like white ribbons, an allusion to the floating freeways of sci-fi cityscapes, and topped by a flashing LED sign that reads “because everything / only really perhaps / yet so limitless”. Perched on a skeletal pedestal that seems to be disintegrating, the piece poignantly conveys the doomed ambitions of modernity’s utopian impulse in the guise of futuristic ruins.

Exhibition view. "Utopia Saved" at the Manege Central Exhibition Hall. Photo by Vasily Bulanov.

Featured: Maquette for Mon grand récit, 2005.

Exhibition view. "Utopia Saved" at the Manege Central Exhibition Hall. Photo by Vasily Bulanov.

Featured: Maquette for Mon grand récit, 2005.

Exhibition view. "Utopia Saved" at the Manege Central Exhibition Hall. Photo by Vasily Bulanov.

Featured: Maquette for Mon grand récit, 2005.

Exhibition view. "Utopia Saved" at the Manege Central Exhibition Hall. Photo by Vasily Bulanov.

Exhibition view. "Utopia Saved" at the Manege Central Exhibition Hall. Photo by Vasily Bulanov.

Exhibition view. "Utopia Saved" at the Manege Central Exhibition Hall. Photo by Vasily Bulanov.

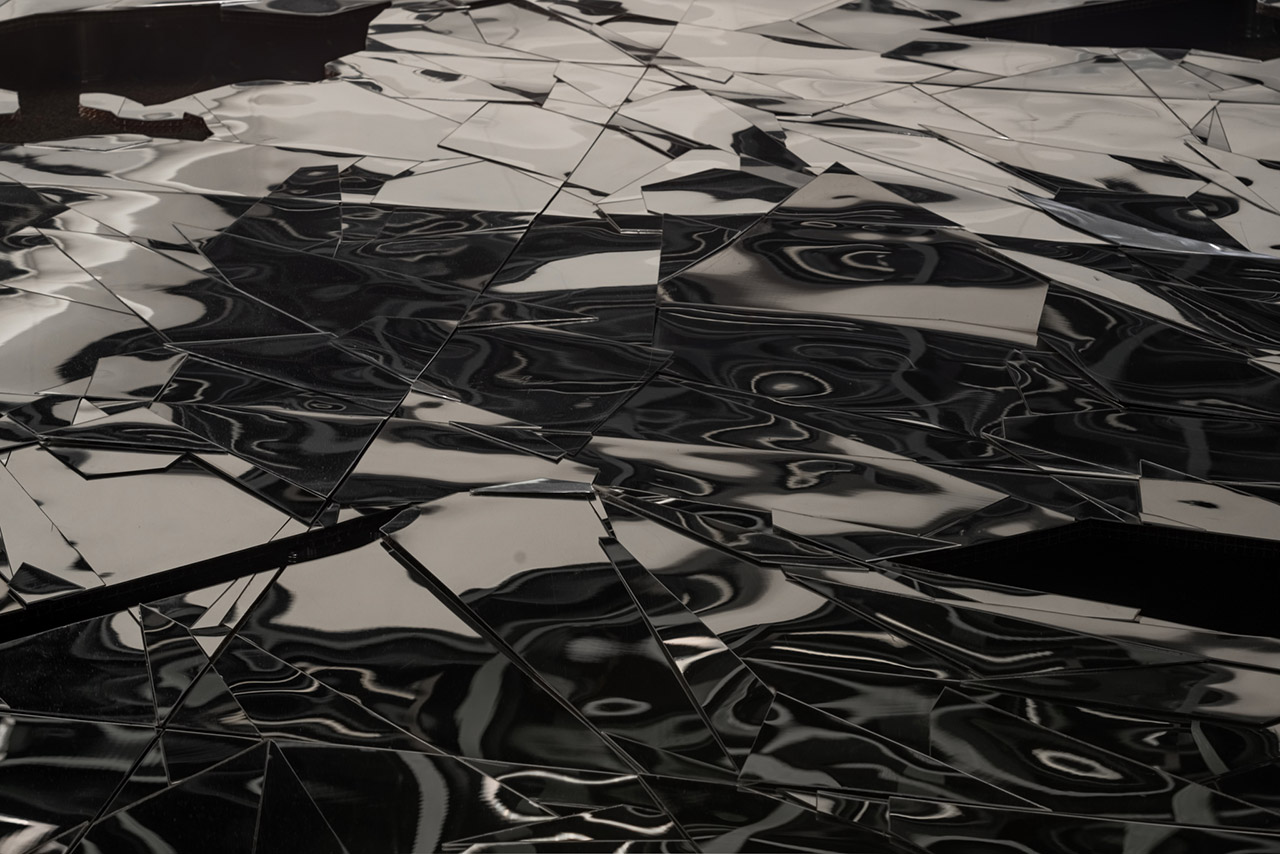

Bul uses a wide range of materials to build her architectural installations but it soon becomes apparent as visitors progress through the exhibition that she’s particularly interested in reflections, mirrors and metallic materials. One of the most engrossing projects on display that exemplifies this interest is Civitas Solis II (2014), a sprawling landscape of mirrored surfaces and flickering lights that takes over a large part of the exhibition hall. The installation takes its name from the Italian philosopher Tommaso Campanella's 1602 book The City of the Sun that describes a utopian world of absolute equality where everyone lived in palaces, and which inspired the drawings of Russian Constructivist architect Ivan Leonidov, some of which are included in the exhibition. Resembling an archipelago of tectonic plates, the installation is awash with distorted reflections thanks to the use of shard-like pieces that make up the mirrored floor sections. Constellations of flickering light points, which spell the work’s title, in conjunction with a mirrored perimeter, enhance the disorientating effect and imbue the space with a dystopian, vigil-like ambiance.

Exhibition view. "Utopia Saved" at the Manege Central Exhibition Hall. Photo by Vasily Bulanov.

Exhibition view. "Utopia Saved" at the Manege Central Exhibition Hall. Photo by Vasily Bulanov.

Featured: Civitas Solis II, 2014.

Civitas Solis II (detail), 2014. Polycarbonate sheet, acrylic mirror, LED lights, electrical wiring, 330 x 3325 x 1850 cm as installed. Commissioned by National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea. Sponsored by Hyundai Motor Company

View of the exhibition, “MMCA Hyundai Motor Series 2014: Lee Bul,” National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, 2014–15

© Lee Bul. Photo: Jeon Byung-cheol. Photo courtesy: National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea

Exhibition view. "Utopia Saved" at the Manege Central Exhibition Hall. Photo by Vasily Bulanov.

Featured: Civitas Solis II (detail), 2014.

Exhibition view. "Utopia Saved" at the Manege Central Exhibition Hall. Photo by Vasily Bulanov.

Featured: Civitas Solis II (detail), 2014.

Exhibition view. "Utopia Saved" at the Manege Central Exhibition Hall. Photo by Vasily Bulanov.

Featured: Civitas Solis II (detail), 2014.

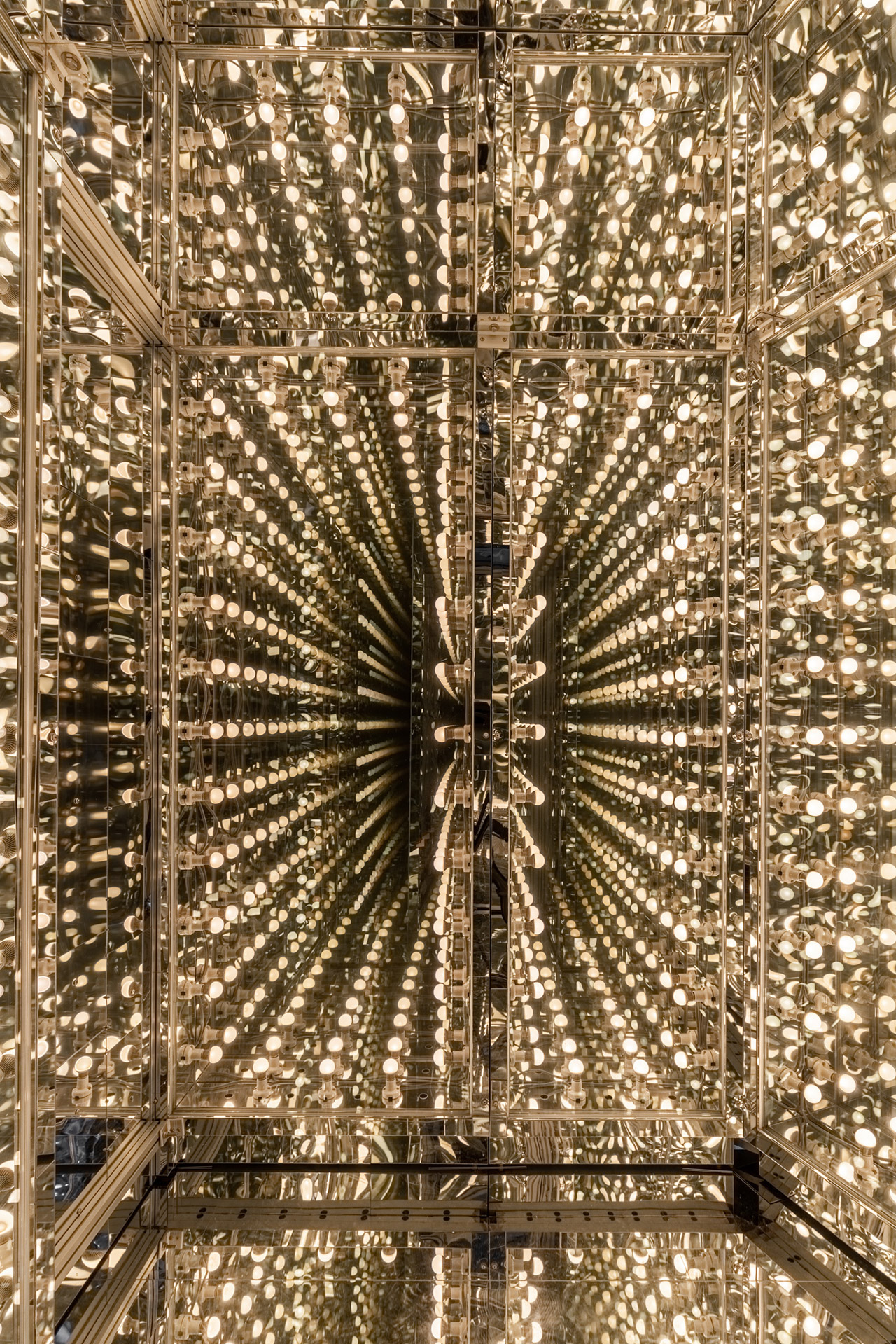

As ambitious and disorientating is Via Negativa II (2014), a mirror-clad structure containing a claustrophobic labyrinth of infinity mirrors and repetitive LED lights that visitors can step into or walk around - in either case, they become a visual element of the installation as their refection is reverberated both within and on the structure. Once inside, although visitors follow a single path, their splintered reflections deceptively give the impression that there are many more. Having to discern what’s real and what’s not disrupts the viewer's perceptual bearings and makes them question their sense of self.

The piece is in fact inspired by psychologist Julian Jaynes and his book on the origins of self-awareness, pages of which have been inversely printed on mirrors, wherein he claims that early man misinterpreted thoughts from the right side of the brain (which is connected to intuition and imagination) as voices from the gods; just as divine nature cannot be understood by reasoning but can only be grasped by defining what it is not, Bul seems to suggest that our self-awareness relies both on the paths we take and those we don’t, hence the titular “negative way”.

Exhibition view. "Utopia Saved" at the Manege Central Exhibition Hall. Photo by Vasily Bulanov.

Featured: Via Negativa II, 2014

Exhibition view. "Utopia Saved" at the Manege Central Exhibition Hall. Photo by Vasily Bulanov.

Exhibition view. "Utopia Saved" at the Manege Central Exhibition Hall. Photo by Vasily Bulanov.

Exhibition view. "Utopia Saved" at the Manege Central Exhibition Hall. Photo by Vasily Bulanov.

Exhibition view. "Utopia Saved" at the Manege Central Exhibition Hall. Photo by Vasily Bulanov.

Exhibition view. "Utopia Saved" at the Manege Central Exhibition Hall. Photo by Vasily Bulanov.

Undoubtedly, the exhibition’s most daring installation is Willing To Be Vulnerable — Metalized Balloon (2015–2016/2020), which centres on a giant, 17-metre-long Zeppelin balloon. Inspired by the Hindenburg disaster that saw the eponymous airship spectacularly consumed by fire as it tried to dock in New Jersey in 1937, the piece recreates one of the most famous albeit doomed symbols of early modernity. Monumental and yet fragile - its shiny, foil-like skin continually flutters courtesy of a few industrial fans. This creation is complemented by a series of historical works that reflect the zeppelin’s once prominent status, from a tin model by scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky circa 1912 - 1914, to an image of a USSR-V6 dirigible floating over Moscow taken by photographer Yakov Khalip between 1936 and 1937, to Aleksandr Labas' 1935 oil painting, The City of the Future, which depicts a blimp suspended amid hazy strokes.

By referencing such a notorious example of modernity’s failed utopian aspirations, Bul both empathises and critiques that era’s ambitions but also draws attention to a subject much closer to our techno-saturated reality: the harmful effects that technology can have even when it’s developed with the best of intentions. On a more basic level, Willing To Be Vulnerable is a bitter-sweet, non-judgmental acknowledgment of our innate urge to attempt impossible tasks. At the end of the day, there’s comfort in knowing that we’ll keep trying to perfect the world, no matter how doomed such attempts inevitably are.

Untitled (Willing To Be Vulnerable - Velvet #9 JTVP 3582/23 CE), 2019

Mother of pearl, acrylic paint, collage on silk velvet, 180 x 130 cm (194 x 144 x 12 cm with frame). The Rachel and Jean-Pierre Lehmann Collection

Photo: Jeon Byung-cheol.

Photo courtesy: Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul and London

Exhibition view. "Utopia Saved" at the Manege Central Exhibition Hall. Photo by Vasily Bulanov.

Willing To Be Vulnerable, 2015–2016/2020.

Heavy-duty fabric, metalized film, transparent film, polyurethane ink, fog machine, LED lighting, electronic wiring, dimensions variable

Installation view of the 20th Biennale of Sydney, 2016

Photo: Algirdas Bakas. Photo courtesy: the artist

Lee Bul © Antonio Campanella. Courtesy: the artist and Frame Magazine