Palazzo Citterio: A New Chapter in Milan’s Cultural Landscape

Words by Eric David

Location

Milan, Italy

Palazzo Citterio: A New Chapter in Milan’s Cultural Landscape

Words by Eric David

Milan, Italy

Milan, Italy

Location

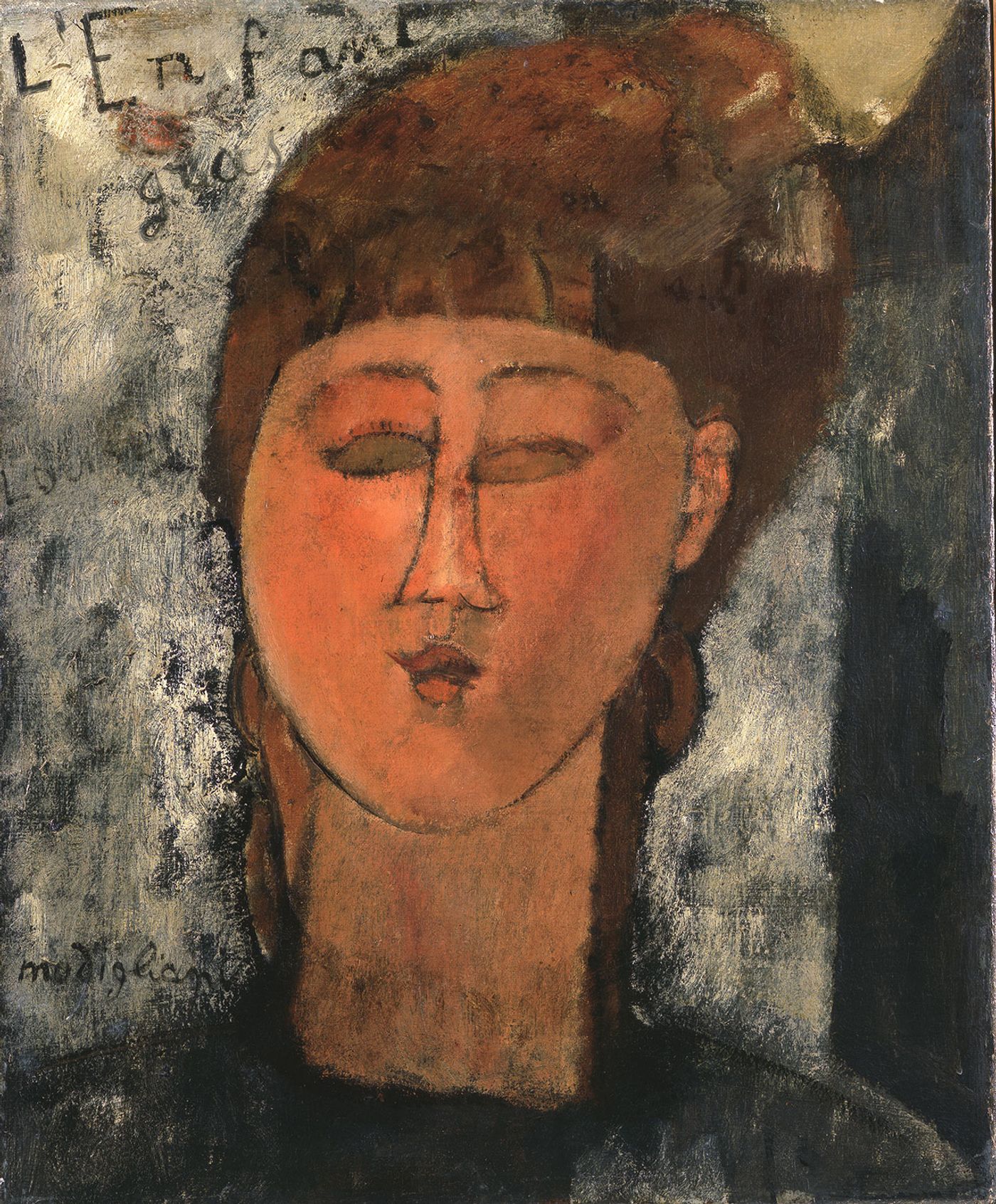

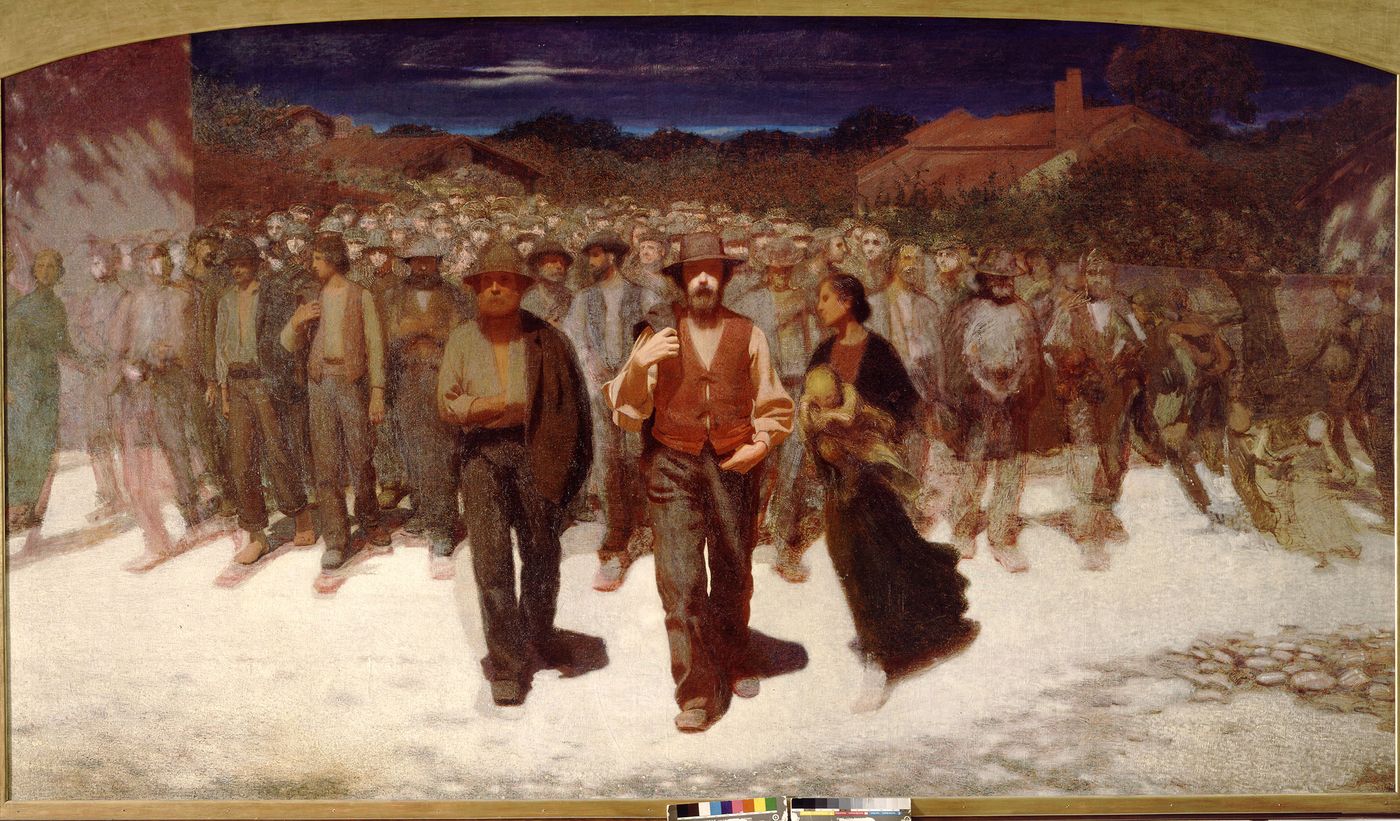

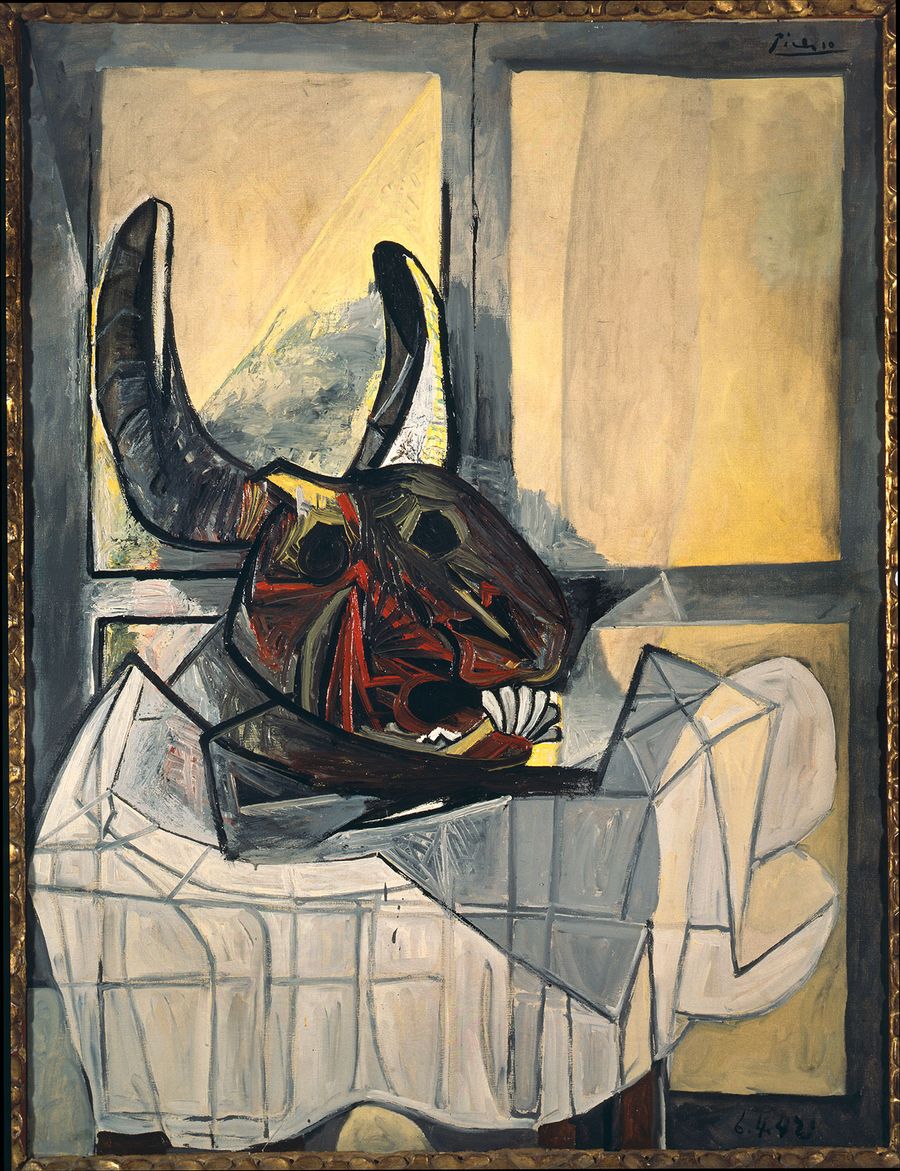

Having opened its doors in December in Milan, Palazzo Citterio realizes a cultural vision over half a century in the making—transformed by Mario Cucinella Architects (MCA) into a dynamic exhibition space dedicated to modern and contemporary art, the historic 18th-century palazzo joins the Pinacoteca di Brera and the Braidense National Library to complete La Grande Brera, a Milanese culture hub bridging the past and future. Now home to over 200 20th century masterpieces—including works by Boccioni, Modigliani, Morandi, and Picasso—alongside immersive contemporary installations and welcoming communal areas, the renewed Palazzo Citterio offers an inspiring setting where history and modernity coexist in a thoughtful dialogue, seamlessly weaving the building’s storied past into its evolving role within Milan’s cultural landscape.

Little Temple. Photography © Walter Vecchio.

Exhibition view. La Grande Brera Una Comunita di Arti e Scienze. Dec 8, 2024 - Mar 10, 2025.

Formerly known as Palazzo Fürstenberg, the 18th-century property was originally built as a private residence in the Barocchetto style. Throughout its two-hundred-year history, the building has undergone numerous transformations, each reflecting the shifting needs and aspirations of its custodians. In 1972, it was acquired by the State with the intention to integrate it into the Brera cultural complex, yet its integration into the museum remained elusive for decades.

One of the most significant interventions came about in the 1980s when the esteemed British architect James Stirling was commissioned to oversee its transformation. His plans, which included a new building to house a library, archives and cafeteria, suffered long delays and were eventually abandoned following his death in 1992. Various efforts to integrate the building into the Brera complex followed, but none came to fruition—that is until now with MCA’s approach which respects the building’s layered history while introducing contemporary elements that enhance both its function and aesthetic appeal.

Exhibition view. La Grande Brera Una Comunita di Arti e Scienze. Dec 8, 2024 - Mar 10, 2025.

Exhibition view. La Grande Brera Una Comunita di Arti e Scienze. Dec 8, 2024 - Mar 10, 2025.

Entrance hall. Photography © Francesco Prandoni. Courtesy of Officine Tamborrino.

The visitor’s experience begins in the museum's new entrance hall, where, contrary to the typical transitional nature of such spaces, they are encouraged to linger. At its heart, an organically-shaped, wood and steel structure, one of a series of bespoke elements that MCA designed for the project, seamlessly integrates ticketing, information, and a gift shop. Featuring built-in seating and shelves for books and souvenirs, the sculptural volume guides visitors along while inviting then to pause and take in their surroundings, including a large LED screen displaying works by digital artists.

Entrance hall. Photography © Francesco Prandoni. Courtesy of Officine Tamborrino.

Testa di Toro (1942) by Pablo Picasso.

Permanent collection. Photography © Walter Vecchio.

Photography © Walter Vecchio.

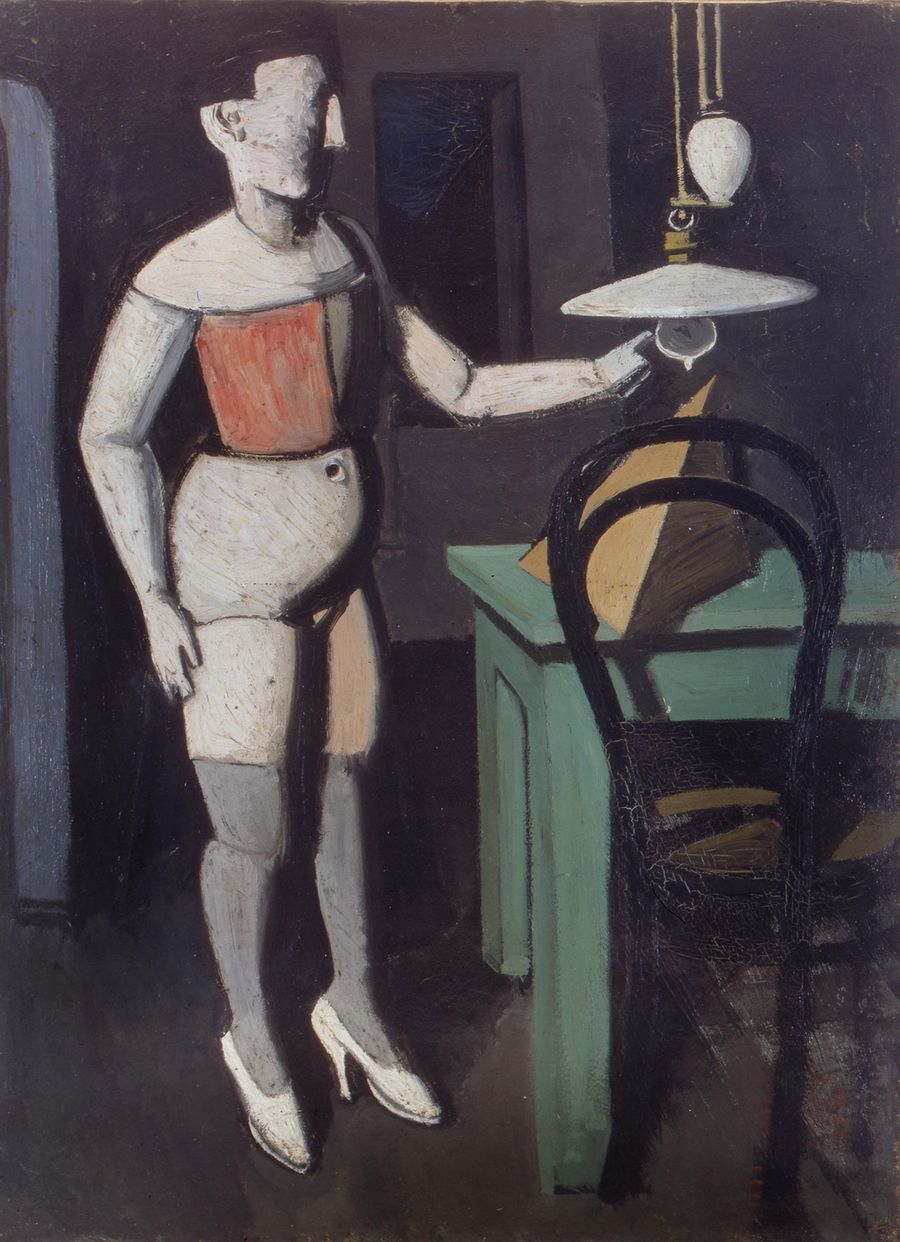

La Lampada (1919) by Mario Sironi.

Permanent collection. Photography © Walter Vecchio.

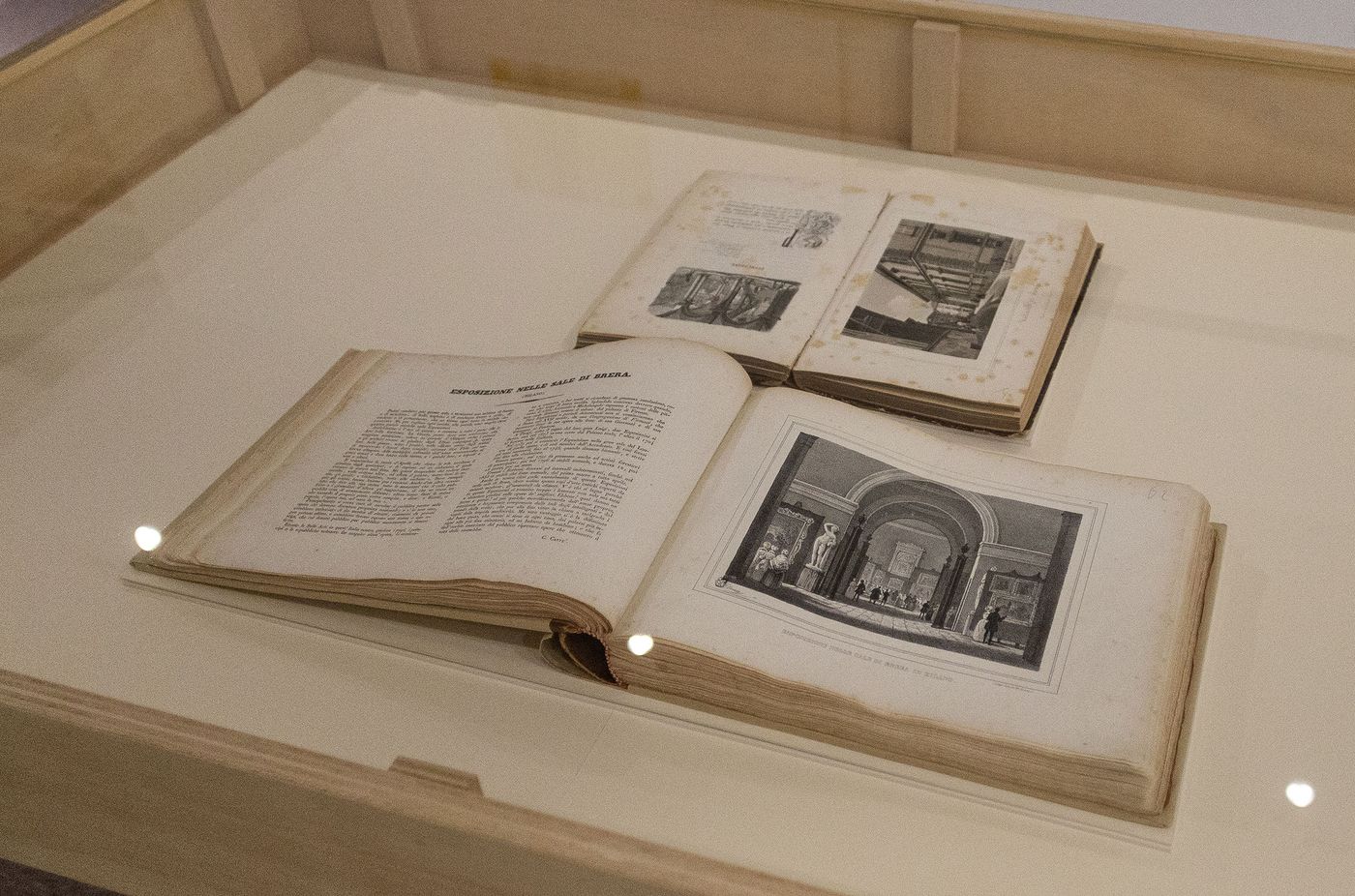

Ascending to the first floor, or the Piano Nobile, a series of stately rooms house Palazzo Critterio’s permanent collection made up of the art collections of the Jesi and Vitali families who once lived here. The Jesi collection, renowned for its modernist masterpieces, encapsulates the dynamism of early twentieth-century Italian art, while the Vitali collection spans an even broader artistic spectrum, featuring not only modern pieces but also archaeological artefacts and rare manuscripts.

Mindful of preserving the historic setting, MCA has carefully integrated minimalist displays that complement rather than compete with the past with each precious exhibit housed in made-to-measure glass vitrines. Designed by the architects and crafted by Goppion Technology, the almost invisible vitrines allow the artifacts to coexist in harmony with the frescoed ceilings, intricate cornices, marble pillars, and other heritage elements. A particularly striking feature is a pair of steel tables, which can be arranged in various configurations, with various sized glass-box displays placed on top of them. Evoking a fine jewellery collection, the set up succeeds in creating an atmosphere that is both grand and intimate at the same time.

Permanent collection. Photography © Walter Vecchio.

Permanent collection. Photography © Walter Vecchio.

Permanent collection. Photography © Walter Vecchio.

Natura Morta con Tavolo Rotondo (1920) by Giorgio Morandi.

Grande Natura Morta Metafisica (1918) by Giorgio Morandi.

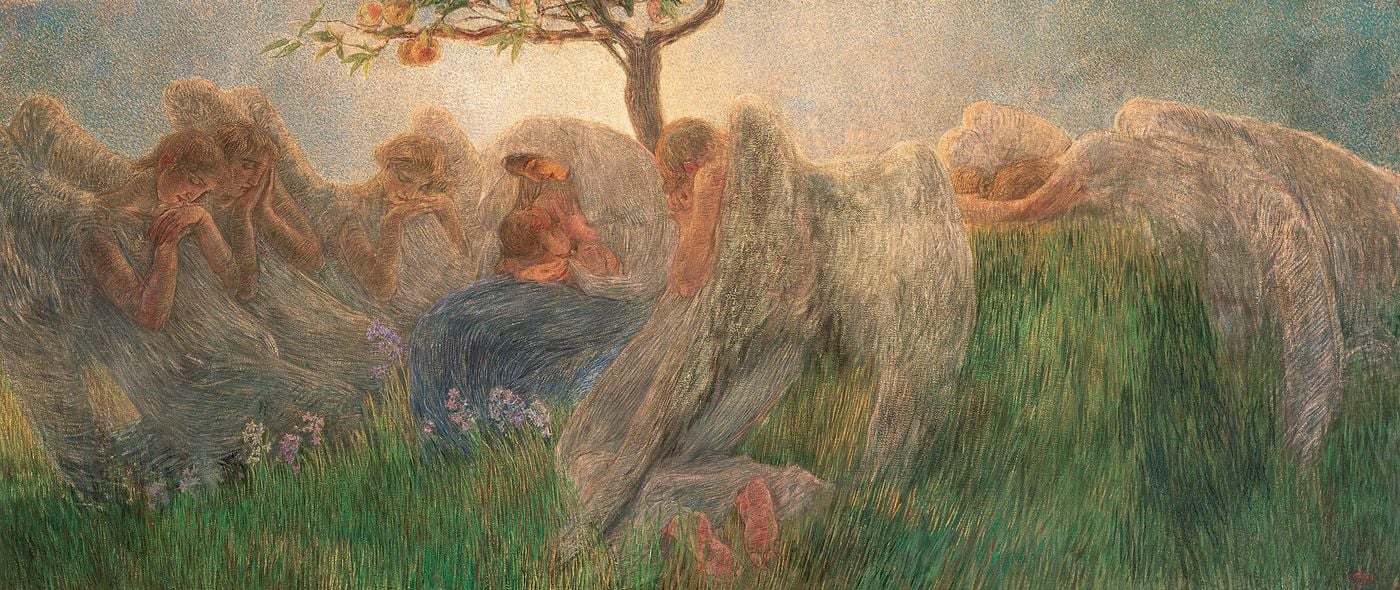

Maternita (1890-1891) by Gaetano Previati.

Artist Mario Ceroli at his studio. Photography by Giorgio Benni.

Additional gallery spaces on the second floor and basement level that host temporary exhibitions attest to Palazzo Citterio’s commitment to contemporary art. Two site-specific installations define this new chapter, namely Mario Ceroli’s sculptural exhibition and Refik Anadol’s digital masterpiece Renaissance Dreams – Capitolo II, Architettura.

Ceroli’s work transforms the exhibition space into a stage of material and form, where wood—his signature medium—becomes a conduit for storytelling. His large-scale sculptures engage with the palazzo’s historical narrative while projecting a distinctively modern energy. Anadol, on the other hand, brings a radically different approach. His immersive digital installation uses AI to reinterpret Renaissance architectural elements, translating them into fluid, data-driven visuals that respond dynamically to their environment.

Exhibition view. Mario Ceroli, La Forza di Sognare Ancora. Dec 8, 2024 - Mar 23, 2025.

Exhibition view. Mario Ceroli, La Forza di Sognare Ancora. Dec 8, 2024 - Mar 23, 2025.

Exhibition view. Mario Ceroli, La Forza di Sognare Ancora. Dec 8, 2024 - Mar 23, 2025.

Refik Anadol, Renaissance Dreams, 2020.

Refik Anadol, Renaissance Dreams, 2020.

Stepping into the courtyard, visitors encounter one of the most distinctive new additions: a small, circular wooden pavilion known as the Little Temple. Donated by Salone del Mobile.Milano, the structure serves as a meeting point between La Grande Brera’s various spaces as well as a figurative bridge between the institution’s historic past and its dynamic future. The pavilion is inspired by Donato Bramante’s Tempietto in Rome, a masterpiece of High Renaissance architecture. Also depicted in Raphael’s The Marriage of the Virgin, which is housed in the Pinacoteca di Brera—and is one of the last artworks visitors encounter before exiting into the courtyard—the pavilion’s historic references are harmoniously balanced with its stark, pared-down design.

Inside, a translucent plastic canopy, akin to a Roman velarium, is suspended above the perimeter benches, creating a serene, almost sacred atmosphere. Boasting a modular construction, the pavilion can be easily transported to the Brera Botanical Garden next door to make space for a temporary bar if the occasion calls for it—an apt metaphor for the entire project’s balance between heritage and innovation. With its doors now open, Palazzo Citterio has finally brought to life the dream of La Grand Brera, offering not just an extension of an illustrious exhibition space but a redefinition of what a museum can be: a space of interaction, reflection, and living history.

Little Temple. Photography © Walter Vecchio.

General Director Pinacoteca Brera Milano and Biblioteca Nazionale Braidense, Angelo Crespi. Photography by Walter Vecchio.

Architect Mario Cucinella. Photography by Julius Hirtzberger.

Luca Molinari, curator of "La Grande Brera Una Comunita di Arti e Scienze" exhibition.