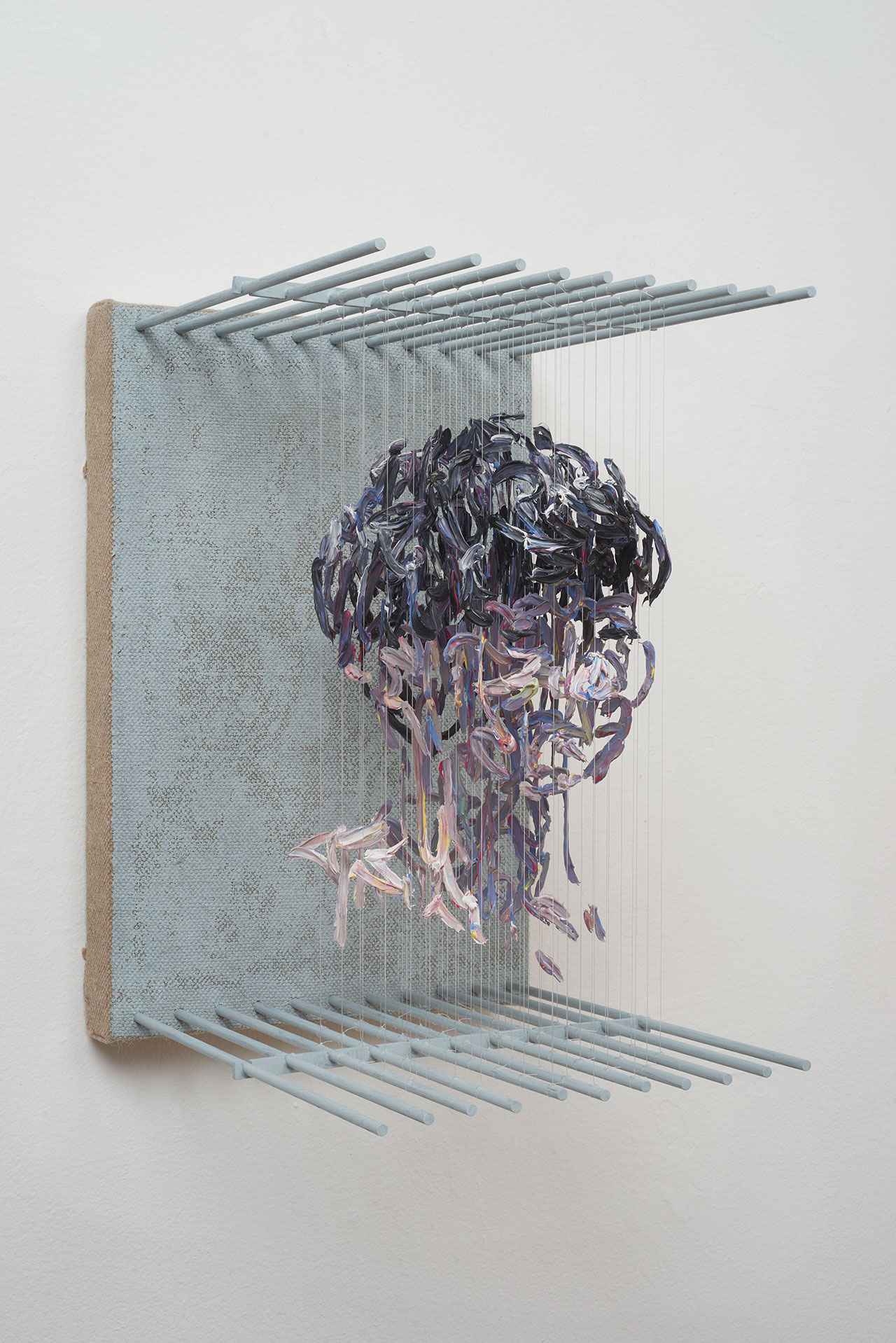

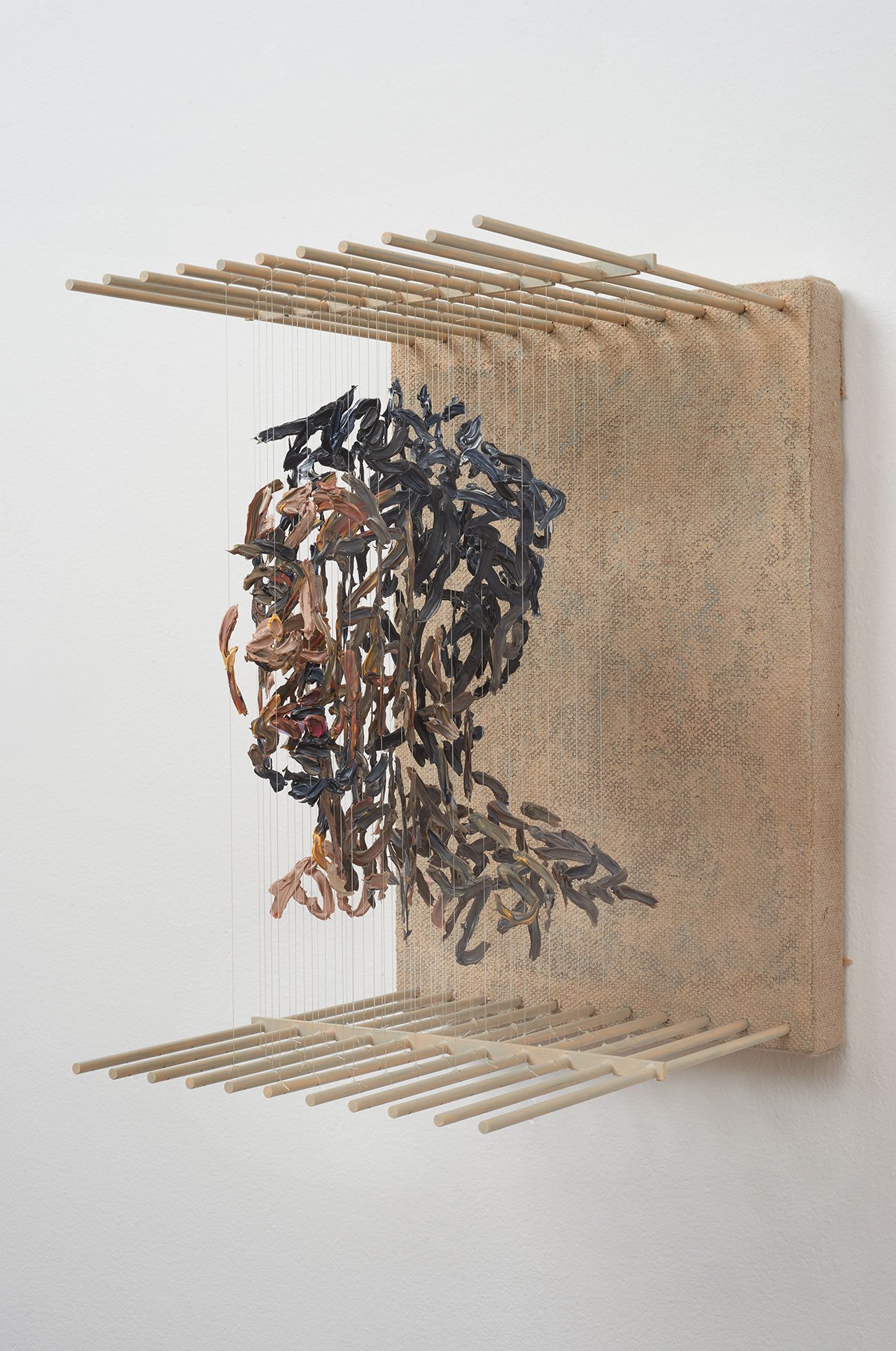

Chris Dorosz, h.o.r, 2017. Acrylic paint on monofilament, metal, jute on board,14 H x 9.25 W x 11D inches. Photo courtesy of Muriel Guépin and the artist.

Chris Dorosz, h.o.r - Side view, 2017. Acrylic paint on monofilament, metal, jute on board,14 H x 9.25 W x 11D inches. Photo courtesy of Muriel Guépin and the artist.

How did your unique technique of suspended paint strokes come about? What was the impetus to paint in three dimensions?

I’ve always been interested in the structure of paint. Moving paint off the canvas has been an evolution over the years. This began with my earlier staple paintings which used paint in relief poured into corals of intricate patterns of industrial staples laid upon their sides on canvas. From this I envisioned a painting exploding into three-dimensional space with my stasis series by dripping paint onto thin, clear plastic rods. In ‘the painted room’, a recreation of my parent’s living room, this became more visceral with splotches of thick acrylic paint suspended on a fishing line. The limitations of paint are just as evident in my work as what paint can do. It is important to convey both awe and humility, two aspects I believe communicate the true nature of our physical reality.

How demanding is it to create sculptures out of paint drops? What is the process that you followed for the Rosh series?

I tend to keep my processes to myself, but I will say that my intention is to always use paint directly without much intervention as well as to create everything by hand without the use of computer intervention. The simplest solutions always work best.

Your work tauntingly hovers between abstraction and representation. What is the allure of each approach for you, both artistically and personally?

I don’t see any difference between abstraction and representation. All image making is about systems. Because of this I see both approaches on a continuum that simply inform one another.

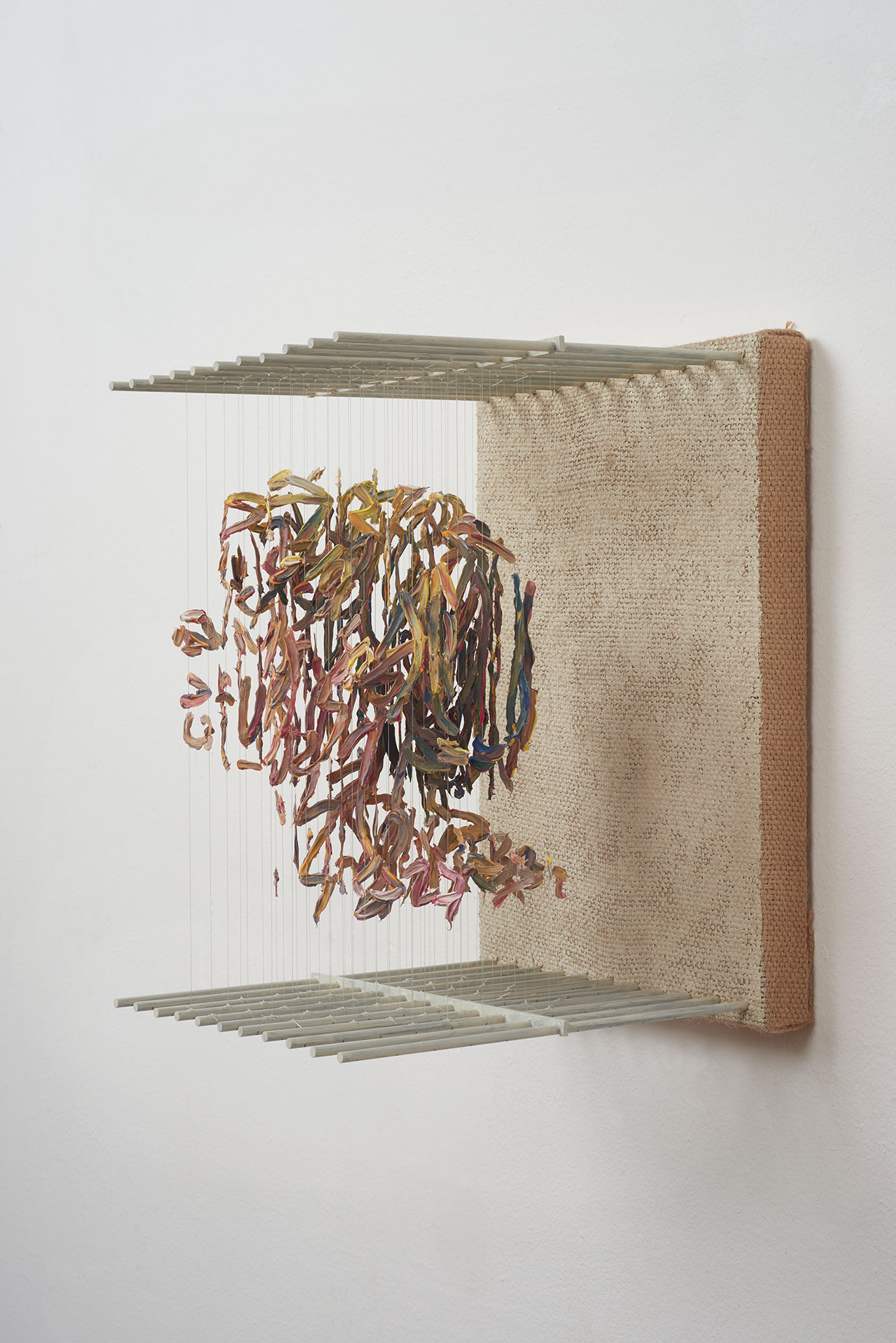

Chris Dorosz, o.h.s - Side View, 2017. Acrylic paint on monofilament, metal, jute on board,14 H x 9.25 W x 11D inches. Photo courtesy of Muriel Guépin and the artist.

Chris Dorosz, o.h.s, 2017. Acrylic paint on monofilament, metal, jute on board,14 H x 9.25 W x 11D inches. Photo courtesy of Muriel Guépin and the artist.

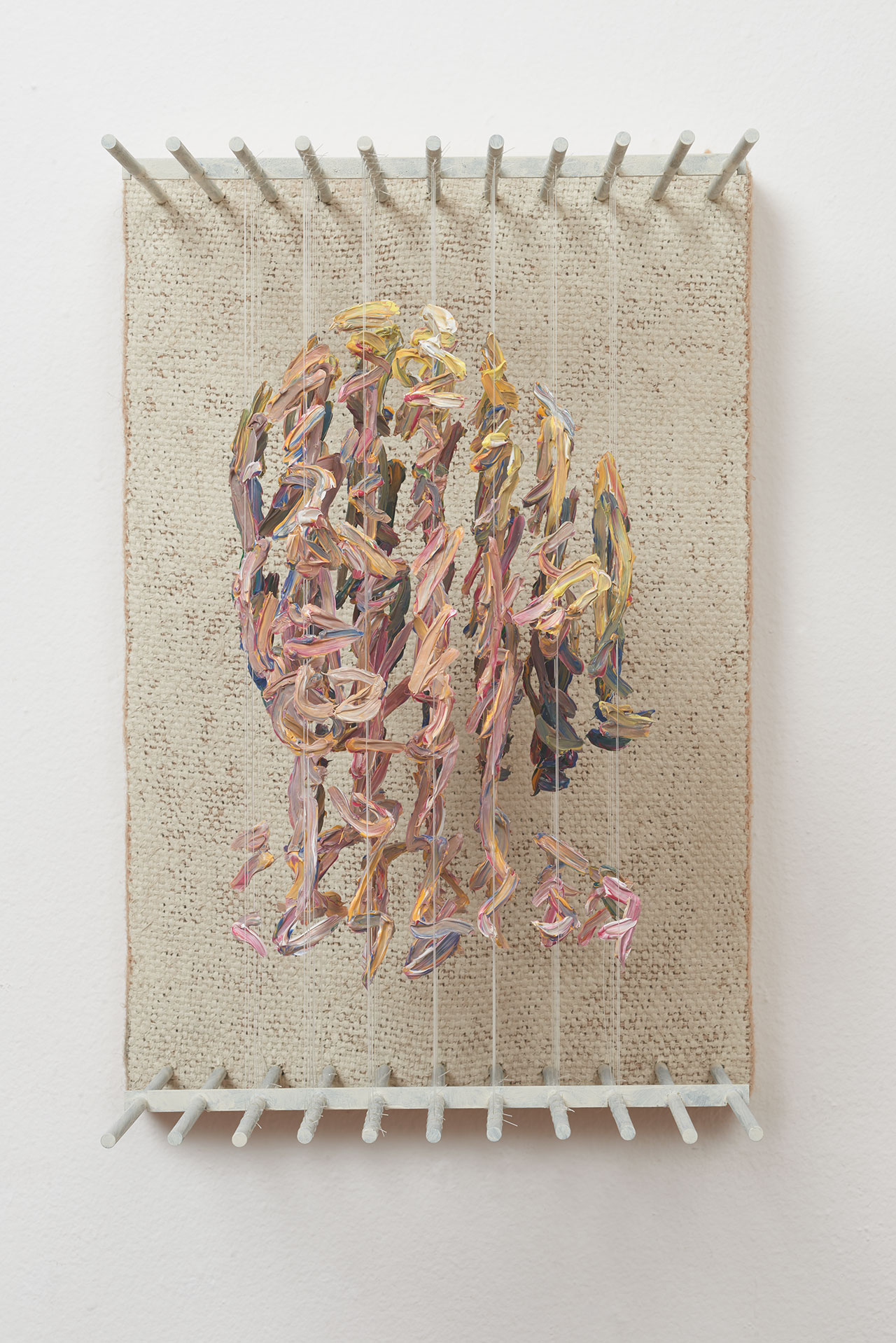

Chris Dorosz, r.s.h, acrylic paint on monofilament, metal, jute on board, 14 H x 9.25 W x 11D inches, 2017. Photo courtesy of Muriel Guépin and the artist.

Why did you chose to do a self-portrait for one of the busts? Is the antithesis between representing a likeness you know best, namely yourself, and its polar opposite, complete strangers, who the other three busts are based on, intentional? And if so, what is the significance?

I started with a self-portrait simply to work with a form that I knew best while figuring this new process out. There was also a bit of an indulgence in documenting myself post the age of 40, especially knowing the approach would be a visceral description of paint/skin and breakdown/decay. Ultimately the Rosh series aren’t portraits, although I do start with the specific in all of my work; through a process that uses mapping and reduction, what I’m left with is the pure form. To further entrench this into my process I had a third party take photos of a random selection of people at the park from which I made a dispassionate selection.

Each piece in the series has been assigned a random three letter monogram taken from the exhibition's title. Is that an allusion to the serendipitous randomness of those contributing factors, genetic and environmental, that make us who we are?

Yes. The letters are meant to convey some type of larger system (genetic and generic) while also referring to a person’s name monogram (usually made up of three letters) representing the specific. I intentionally hover between these two poles in all of my work.

You have managed to create a hybrid medium that marries painting and sculpture. Do you consider yourself more of a painter or a sculptor?

I’m doing both for sure but I do think of myself as a painter as all of my work is concerned with the possibilities (and limitations) of paint.

Is the union of these two very distinct yet classical mediums the outcome of creative experimentation and personal taste, or does it also speak to the limitation of classical art mediums in the digital age?

No on both counts. A painting is an object first and foremost. How thick is the canvas or paint coming off of the wall? How does the light rake across its surface? There are many factors like these which are sculptural considerations and are lost if painting is only considered as image. Both painting and sculpture deal with aspects whether real or illusionistic of three-dimensional space. In terms of digital mediums, I believe there is always a sadness in them because they lack aspects of the physical dimension, a big one being texture. I see this as limiting no matter how complex CGI becomes.

Installation view of the Rosh Series. Photo courtesy of Muriel Guépin and the artist.

You have compared the paint drops you use in your work to the building blocks that make up the human body and the pixels which digital images are comprised of. How important is this organic sensibility in your art and how does it inform the issues you tackle?

It is the basis for everything that I do. In the mid-nineties when I was coming out of grad school I asked myself why I wanted to work with paint in an age exploding with digital possibilities. The answer I came up with utilized paint as a metaphor to explore ideas of human physicality in a world pushing towards the virtual. All digital systems could crash and we could still make imagery by scratching a line in the sand to represent something. Paint like sand is a materia prima and intrinsically holds an organic sensibility which to me is spiritual; ashes to ashes and dust to dust.

Your previous work also shares the deconstructive sensibility of the Rosh series whereby the viewer is asked to visually reconstruct the fragmented work in front of him. Why is it important for you to visually challenge the viewer? Do you believe that art is best served by challenging its audience and asking questions as opposed to providing answers?

Most definitely. Art never provides answers; it must be left open-ended intentionally. That is why art that is too didactic or self-consciously political tends to fall flat. I also believe in the notion of “communing” with artwork. The idea of being in front of the work, alone and thinking, and coming back to it again and again, either in order to see new things or to reaffirm what we already knew.

What are you working on now? Are you planning to evolve your three-dimensional painting technique even further?

I’m about to begin a project in 2018 titled ‘Dark Matter House’. With a hand held 3-d scanner and a clairvoyant medium by my side I want to digitally and psychically “map” an old salt box house on the far coast of Newfoundland. The resulting data will be used back in the studio to explore ideas of multiple dimensions, intangible energies and negative space.

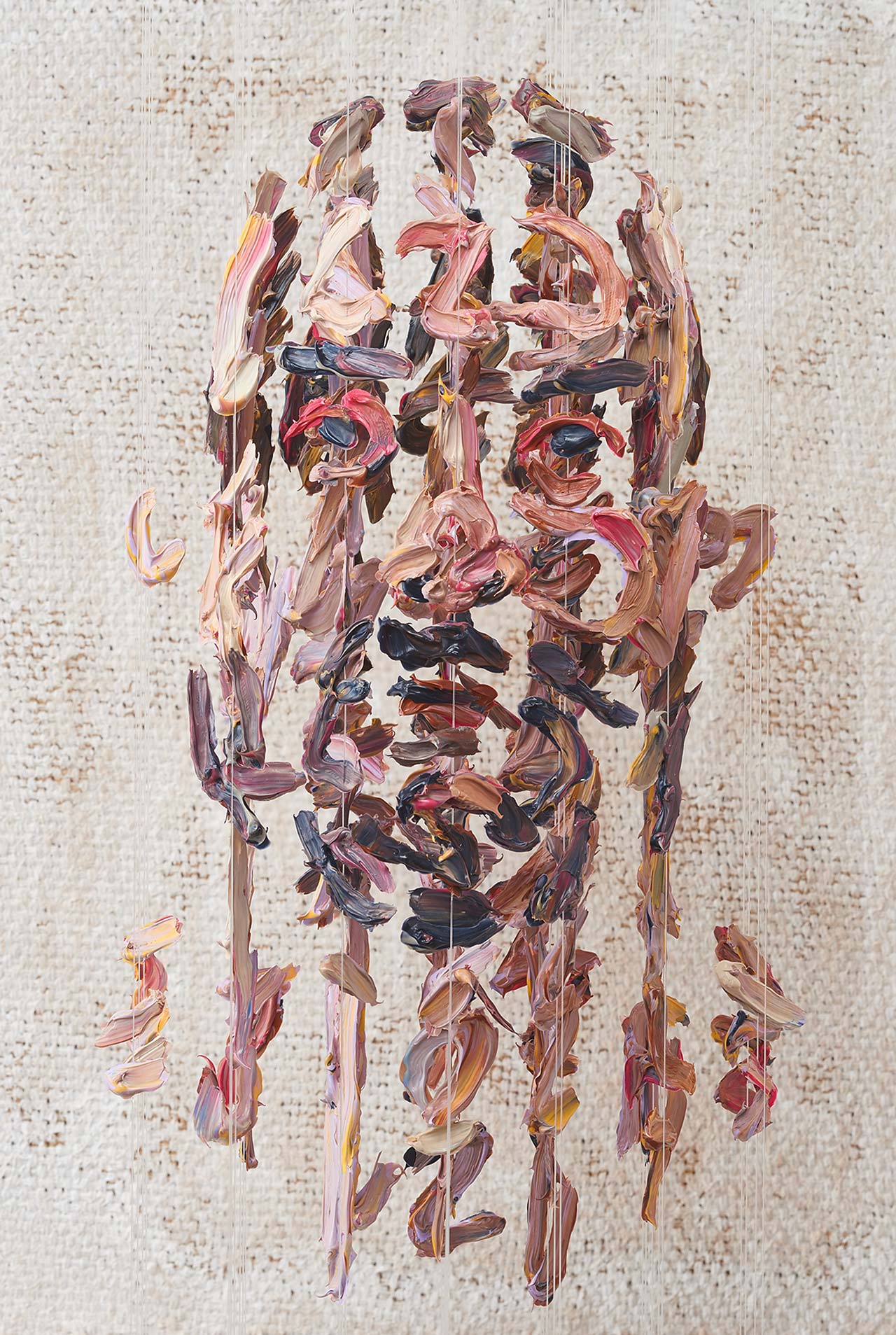

Chris Dorosz, s.r.o, 2017. Acrylic paint on monofilament, metal, jute on board ,14 H x 9.25 W x 11D inches. Photo courtesy of Muriel Guépin and the artist.

Chris Dorosz, s.r.o - Side View, 2017. Acrylic paint on monofilament, metal, jute on board ,14 H x 9.25 W x 11D inches. Photo courtesy of Muriel Guépin and the artist.