Title

Mapplethorpe+MunchPosted In

Painting, Photography, ExhibitionDuration

06 February 2016 to 29 May 2016Venue

The Munch MuseetOpening Hours

Every Day 10.00 - 16.00Location

Telephone

(+47) 23 49 35 00Visit Website

munchmuseet.no| Detailed Information | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title | Mapplethorpe+Munch | Posted In | Painting, Photography, Exhibition | Duration | 06 February 2016 to 29 May 2016 |

| Venue | The Munch Museet | Opening Hours | Every Day 10.00 - 16.00 | Location |

Tøyengata 53 0578 Oslo

Norway |

| Telephone | (+47) 23 49 35 00 | [email protected] | Visit Website | munchmuseet.no | |

The exhibition, presenting 141 works from Mapplethorpe and 95 from Munch, is divided in several thematic sections—self-portraits, the female nude, faces & flowers and sexuality—demonstrating how both artists extensively used two traditional genres, nudes and portraits to explore common themes such as sexual liberation, gender, identity and religious aspiration. Both being members of a bohemian subculture of artists, and emerging during a time of cultural change and upheaval (Munch in the 1880s and Mapplethorpe the 1970s), the pairing of their work also draws attention to their shared defiance of the establishment and their attempt to stretch the boundaries of their art.

Mapplethorpe + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016).

Installation view.

Photo by Vegard Kleven.

Self-portraits

The exhibition begins with Mapplethorpe’s black and white self-portrait from 1988, taken only months before he died from an AIDS-related illness, which is presented side-by-side with Munch’s “Self-Portrait with Skeleton Arm”, a monochrome lithograph from 1895; the two works share a similar visual composition and an acute awareness of mortality.

Both artists were prolific in producing self-portraits throughout their careers. For Mapplethorpe, personality was considered “serial” as the critic Peter Conrad asserts, and in his self-portraits he often therefore takes different roles, depicting himself dressed as a woman, a hoodlum or a terrorist. Munch’s self-portraits also serially depict the artist in various stages in his life, from his arrogant and self-assured younger self, to a drunken, catatonic middle age self, all the way to the sick, ageing self of his final years.

Mapplethorpe + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016).

Installation view.

Photo by Vegard Kleven.

Mapplethorpe + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016).

Installation view.

Photo by Vegard Kleven.

Hung next to each other, Munch’s “Self-portrait in Hell” (1903) and Mapplethorpe’s self-portrait with devil horns (1985) share the same eerie self-awareness, the former capturing the artist’s sense of suffering and misery whereas the latter captures the artist’s darker side. In the same section, Munch’s series of photographic self-portraits from the early 20th century viewed alongside Mapplethorpe’s Polaroids of himself exploring his sexuality —this is in fact the only time they use the same medium— reveal their willingness to expose themselves with brutal honesty.

Mapplethorp + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016).

Installation view.

Photo by Vegard Kleven.

Mapplethorp + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016).

Installation view.

Photo by Ove Kvavik.

Courtesy the Munch Museum.

Sexuality

Provocation was an integral part of both Munch’s and Mapplethorpe’s art, as well as a tool to advance their careers. Mapplethorpe’s explicit sexual imagery caused quite a stir in the 1970’s and 1980’s with several of his planned exhibitions cancelled under the pressure of conservative groups; in a similar way, Munch’s frank representations of sexuality and unconventional painting techniques caused critical outrage back in the 1890’s.

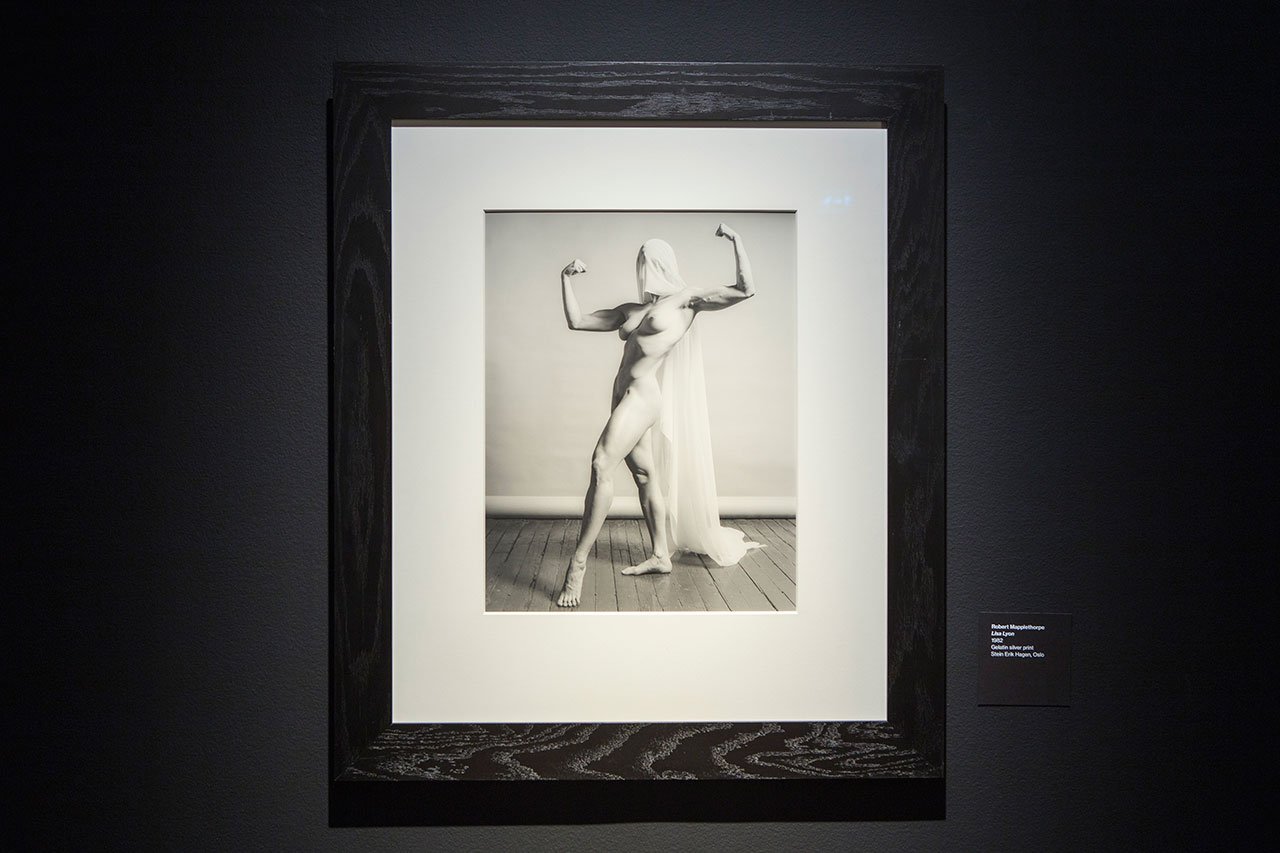

Munch’s painting and lithographs of a naked, sensual Madonna depicted as both a saint and a demon in the middle of intercourse, is indicative of his uninhibited approach exploring sexuality. Viewed next to Mapplethorpe’s series of women photographed in suggestive poses ranging from sexual seduction to veiled anonymity, the similarity between the two artists’ preoccupations is made clear. In other points of contact, Munch’s image of two lovers fusing together in a tender embrace (“Kiss”, 1897), is reflected in Mapplethorpe’s photograph of a white and black man locked in a embrace (“Embrace” 1982), whereas Munch’s brothel series foreshadows Mapplethorpe’s X Portfolio that portrays the underground S&M scene in New York.

Mapplethorp + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016).

Installation view.

Photo by Vegard Kleven.

Nudes

In another parallel arc in their lives, not only did both Mapplethorpe and Munch work extensively with female nudes, they also each had a muse who inspired them to produce series of work. For Munch it was Annie Fjeldbu who sat for him for five years around 1920 and can be viewed in several full-length poses along Mapplethorpe's model, Lisa Lyon, a pioneer in female body building, whom he photographed during three years in the early 80s in numerous stereotype-breaking roles. Parallels can also be found in the two artists’ exploration of the male nude: in Munch’s “Standing Naked African” (1916) and Mapplethorpe’s images of naked black men, there is a pronounced sculptural quality, a glowing physicality elevated to the Platonic ideal of human form.

Mapplethorp + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016).

Installation view.

Photo by Ove Kvavik.

Courtesy the Munch Museum.

Mapplethorp + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016).

Installation view.

Photo by Ove Kvavik.

Courtesy the Munch Museum.

Mapplethorp + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016).

Installation view.

Photo by Ove Kvavik.

Courtesy the Munch Museum.

Portraits

Both artists excelled at creating portraits, most notably of famous friends and acquaintances, many of them on commission. The objective behind Mapplethorpe’s portraiture was to get at the plurality and fluidity of a person’s identity, something that can be sensed in Munch’s work too. His portrait of Dagny Juel Przybyszewska (1893)—a Norwegian writer, famous for her liaisons with various prominent artists, and for the dramatic circumstances of her death—displayed next to Mapplethorpe’s photograph of Grace Jones (1975), although quite different in aesthetics, style and size, the one a coloured oil painting, the other a black and white photograph, both carry a distinct emotional weight with the two women exuding both vulnerability and self-assurance.

Mapplethorp + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016).

Installation view.

Photo by Ove Kvavik.

Courtesy the Munch Museum.

Mapplethorp + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016).

Installation view.

Photo by Ove Kvavik.

Courtesy the Munch Museum.

Coming full circle the exhibition concludes with Munch’ self-portrait as a naked, ageing man and Mapplethorpe’s final self-portrait before his death showing just his eyes, successfully threading together the two artists’ oeuvre and lives in a coherent narrative of self-exploration. It is also a reminder that art, with its relentless exploration of the human condition, is timeless and universal.

Mapplethorp + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016).

Installation view.

Photo by Ove Kvavik.

Courtesy the Munch Museum.

Mapplethorp + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016).

Installation view.

Photo by Ove Kvavik.

Courtesy the Munch Museum.

Mapplethorp + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016).

Installation view.

Photo by Vegard Kleven.

Mapplethorp + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016).

Installation view.

Photo by Vegard Kleven.

Mapplethorp + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016).

Installation view.

Photo by Vegard Kleven.

Mapplethorpe + Munch exhibition poster.

Courtesy the Munch Museum.