While the Ice is Melting: An Immersive Exhibition in Stockholm and a Photo Book by Michel Rawicki Explore Life in the Arctic

Words by Eric David

Location

Stockholm, Sweden

While the Ice is Melting: An Immersive Exhibition in Stockholm and a Photo Book by Michel Rawicki Explore Life in the Arctic

Words by Eric David

Stockholm, Sweden

Stockholm, Sweden

Location

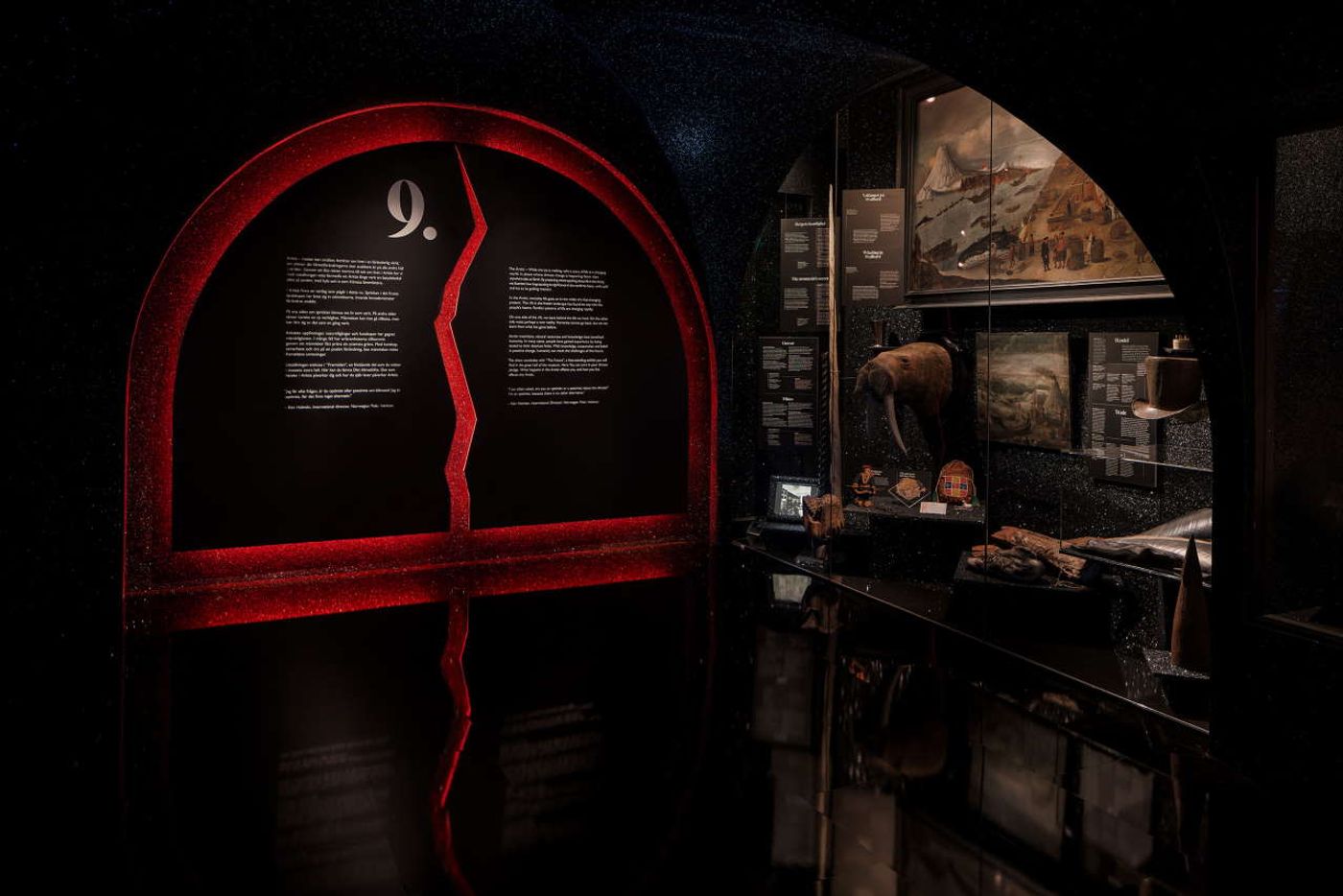

In August, the first ever loss of a glacier due to climate change was marked by a symbolic funeral in Iceland. Unfortunately, this is no isolated event; glaciers, polar land, and sea ice are melting much faster than scientists originally predicted as global temperatures rise. During a five-day heat wave this summer, Greenland lost 55 billion tons of ice mirroring the record-breaking ice loss in 2012 while the latest projections talk of ice-free Arctic summers in 10 to 40 years. Rising sea levels may be the first thing that comes to mind when contemplating these dire predictions but we tend to forget the four million people inhabiting the Arctic region and the challenges they are already facing. An immersive exhibition at Stockholm’s Nordiska museet redresses this by shining a light on Arctic life, past and present, and the region’s changing conditions. Titled “The Arctic – While the Ice Is Melting” and scheduled to run for three years, the exhibition was designed by Award-winning design duo Sofia Hedman and Serge Martynov of MUSEEA in collaboration with experts from Stockholm University and numerous researchers stationed in the Arctic, and includes exhibits, ceiling projections, interactive stations as well as ten documentary films.

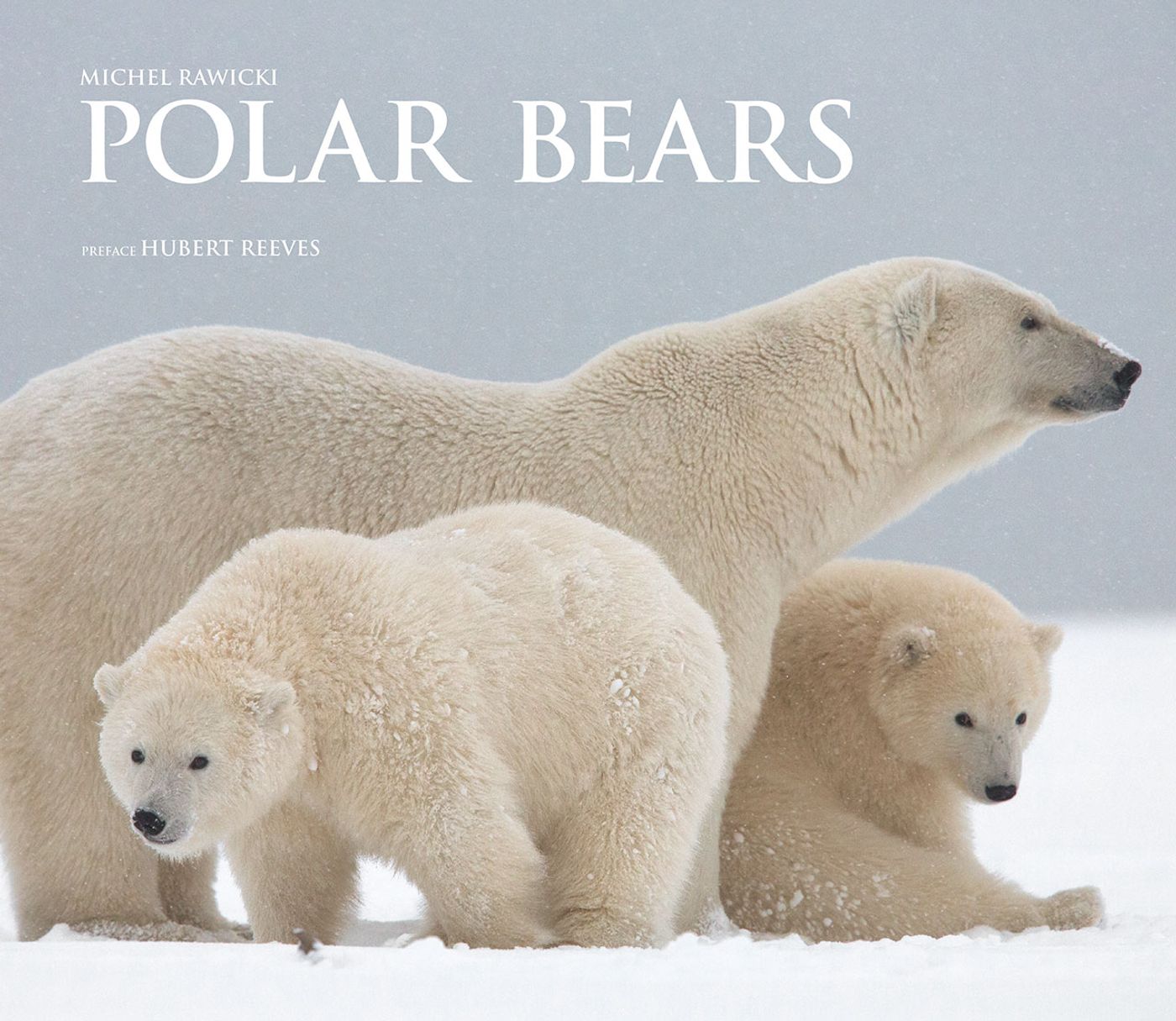

Whereas MUSEEA’s exhibition showcases the toll of climate change on human life, a new photography book by French photographer Michel Rawicki, out now by ACC Art Books, examines another Arctic inhabitant, the polar bear. Twenty-five years in the making, “Polar Bears – A life under threat” is a pictorial ode to the iconic animal and its endangered habitat, as well as a timely reminder of its uncertain future.

The Arctic - While the Ice is Melting, Nordiska museet, Stockholm. Exhibition view. Photo by Hendrik Zeitler.

The Arctic - While the Ice is Melting, Nordiska museet, Stockholm. Exhibition view. Photo by Hendrik Zeitler.

The Arctic - While the Ice is Melting, Nordiska museet, Stockholm. Exhibition view. Photo by Hendrik Zeitler.

The Arctic - While the Ice is Melting, Nordiska museet, Stockholm. Exhibition view. Photo by Hendrik Zeitler.

Dominating the Nordiska museet’s Great Hall, a monumental iceberg invites visitors to step inside through a giant crack, a symbolic rift between past and present. Inspired by Doris Salcedo's “Shibboleth" installation at London's Tate Modern in 2007, the calving iceberg contains a series of objects, most of which are from the museum’s own collection, as well as artworks, films, slideshows and webcams that illuminate the everyday lives of the people in the Arctic and the challenges they face in an ever warmer planet in addition to shedding light on the region’s history. As visitors progress through the iceberg, mesmeric projections of hard white ice gradually give way to light green and blue meltwater, eventually melting entirely into the dark deep blue sea, in what is a subtle allusion to the exhibition’s title, “While the Ice Is Melting”.

The Arctic - While the Ice is Melting, Nordiska museet, Stockholm. Exhibition view. Photo by Hendrik Zeitler.

The Arctic - While the Ice is Melting, Nordiska museet, Stockholm. Exhibition view. Photo by Hendrik Zeitler.

The Arctic - While the Ice is Melting, Nordiska museet, Stockholm. Exhibition view. Photo by Hendrik Zeitler.

The Arctic - While the Ice is Melting, Nordiska museet, Stockholm. Exhibition view. Photo by Hendrik Zeitler.

The Arctic - While the Ice is Melting, Nordiska museet, Stockholm. Exhibition view. Photo by Hendrik Zeitler.

The Arctic - While the Ice is Melting, Nordiska museet, Stockholm. Exhibition view. Photo by Hendrik Zeitler.

The exhibition highlights the ingenuity, inventiveness and creativity that surviving in the extreme Arctic climate entails – think clothes made from the skins of polar and brown bears, ermine, seals and birds, embroidered with leather and decorated with marten skin and glass beads. It also demonstrates how a changing landscape has upended centuries of traditions and habits. Melting ice for example means that instead of walking, or using sleighs and scooters, people are increasingly taking boats and helicopters, while thawing permafrost makes living in houses made of wood or concrete much more difficult as the soil cracks. In fact cracks seems to be the underlying theme of the exhibition, be they geological or symbolic, such as the widening gap between animals and their food, or the rift between those who protect the environment and those who want to exploit it for financial gain. But cracks can also be an agent for change; by being impossible to ignore they can spur people into action.

The Arctic - While the Ice is Melting, Nordiska museet, Stockholm. Exhibition view. Photo by Hendrik Zeitler.

The Arctic - While the Ice is Melting, Nordiska museet, Stockholm. Exhibition view. Photo by Hendrik Zeitler.

The Arctic - While the Ice is Melting, Nordiska museet, Stockholm. Exhibition view. Photo by Hendrik Zeitler.

The Arctic - While the Ice is Melting, Nordiska museet, Stockholm. Exhibition view. Photo by Hendrik Zeitler.

The Arctic - While the Ice is Melting, Nordiska museet, Stockholm. Exhibition view. Photo by Hendrik Zeitler.

The Arctic - While the Ice is Melting, Nordiska museet, Stockholm. Exhibition view. Photo by Hendrik Zeitler.

Other installations that MUSEEA have designed for the exhibition include a circular display that echoes the round forms of Arctic tents, a sculptural composition of timber slats inspired by the triangular rooflines in Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Greenland and Siberia, and a gallery constructed out of organic materials such as hay that alludes to the sustainable way of life that used to be the norm in the Arctic. A much darker space towards the end of the show resembles a section of a huge oil pipe where visitors learn about the effects of large-scale resource extraction in the Arctic, an expanding industry that is taking advantage of the melting of the permafrost.

The Arctic - While the Ice is Melting, Nordiska museet, Stockholm. Exhibition view. Photo by Hendrik Zeitler.

The Arctic - While the Ice is Melting, Nordiska museet, Stockholm. Exhibition view. Photo by Hendrik Zeitler.

The Arctic - While the Ice is Melting, Nordiska museet, Stockholm. Exhibition view. Photo by Hendrik Zeitler.

The Arctic - While the Ice is Melting, Nordiska museet, Stockholm. Exhibition view. Photo by Hendrik Zeitler.

The Arctic - While the Ice is Melting, Nordiska museet, Stockholm. Exhibition view. Photo by Hendrik Zeitler.

The Arctic - While the Ice is Melting, Nordiska museet, Stockholm. Exhibition view. Photo by Hendrik Zeitler.

The Arctic - While the Ice is Melting, Nordiska museet, Stockholm. Exhibition view. Photo by Hendrik Zeitler.

The Arctic - While the Ice is Melting, Nordiska museet, Stockholm. Exhibition view. Photo by Hendrik Zeitler.

The Arctic - While the Ice is Melting, Nordiska museet, Stockholm. Exhibition view. Photo by Hendrik Zeitler.

The exhibition concludes as dramatic as it started with a complex system of projections by Jesper Wachtmeister on the Great Hall’s 20 metre-high vaulted ceiling. Visitors can take a seat and enjoy an immersive spectacle of Arctic landscapes and Arctic skies, sourced primarily from Nordiska museet’s collection of contemporary photos and films.

The Arctic - While the Ice is Melting, Nordiska museet, Stockholm. Exhibition view. Photo by Hendrik Zeitler.

The Arctic - While the Ice is Melting, Nordiska museet, Stockholm. Exhibition view. Photo by Hendrik Zeitler.

The Arctic - While the Ice is Melting, Nordiska museet, Stockholm. Exhibition view. Photo by Hendrik Zeitler.

Bakanbukta, Svalbard, Norway.

Photo by Michel Rawicki © ACC Arts Books Ltd © Albin Michel.

Bakanbukta, Svalbard, Norway.

Photo by Michel Rawicki © ACC Arts Books Ltd © Albin Michel.

Comprising two hundred photographs taken over the course of 25 years on countless trips from Alaska to Siberia, “Polar Bears – A life under threat” pays homage to an extraordinary creature synonymous with the region (“Arctic” comes from the Ancient Greek word for bear), whose plight has become the emblem of global warming – and for good reason, polar bears are completely dependent on the presence of sea ice. “Valiant conquerors of the vast snowy wastes” in Michel Rawicki’s words, polar bears have always fascinated people, looming large in our collective imagination both as ferocious beasts and as mythic figures whose iconic figure has been widely reproduced in soft toys, logos and commercials.

Wapusk National Park, Manitoba, Canada.

Photo by Michel Rawicki © ACC Arts Books Ltd © Albin Michel.

Wapusk National Park, Manitoba, Canada.

Photo by Michel Rawicki © ACC Arts Books Ltd © Albin Michel.

Kaktovik, Barter Island, Alaska, USA.

Photo by Michel Rawicki © ACC Arts Books Ltd © Albin Michel.

Churchill and Wapusk National Park, Manitoba, Canada.

Photo by Michel Rawicki © ACC Arts Books Ltd © Albin Michel.

Churchill and Wapusk National Park, Manitoba, Canada.

Photo by Michel Rawicki © ACC Arts Books Ltd © Albin Michel.

Polar bears are long-distance travellers, covering hundreds of kilometres on foot or by water although no one has discovered what motivates them yet which only adds to their mystical allure. Their nomadic life is reflected in their adaptable eating habits; in some places they fish for Arctic char, in others, they eat bilberries or hunt seals, whereas in Churchill, Canada, they lie in wait for the tide to wash beluga whales closer to the shore. Procreation is just as episodic; polar bear cubs are born blind and bold, and spend their first three months in the warmth of an underground den, so when they finally step out into the harsh Arctic landscape at the end of February or early March a crash course in survival awaits if they are to follow their mother across the ice floe.

Rawicki has captured these magnificent animals across different Arctic regions, seasons and circumstances, lyrically showcasing the beauty as well as the hardship of life in the Arctic. As distant from our everyday lives as these photographs may seem, the threats that climate change poses to their mammalian survival are not that different in severity or scope from the dangers that we ourselves are potentially facing.

Nelson River, Hudson Bay, Manitoba, Canada.

Photo by Michel Rawicki © ACC Arts Books Ltd © Albin Michel.

Karl XII-øya, Svalbard, Norway.

Photo by Michel Rawicki © ACC Arts Books Ltd © Albin Michel.

Savissivik, northwest coast, Greenland, Denmark.

Photo by Michel Rawicki © ACC Arts Books Ltd © Albin Michel.

Wapusk National Park, Manitoba, Canada.

Photo by Michel Rawicki © ACC Arts Books Ltd © Albin Michel.

Michel Rawicki - Polar Bears, Book Cover. Kaktovik, Barter Island, Alaska, USA.

Photo by Michel Rawicki © ACC Arts Books Ltd © Albin Michel.