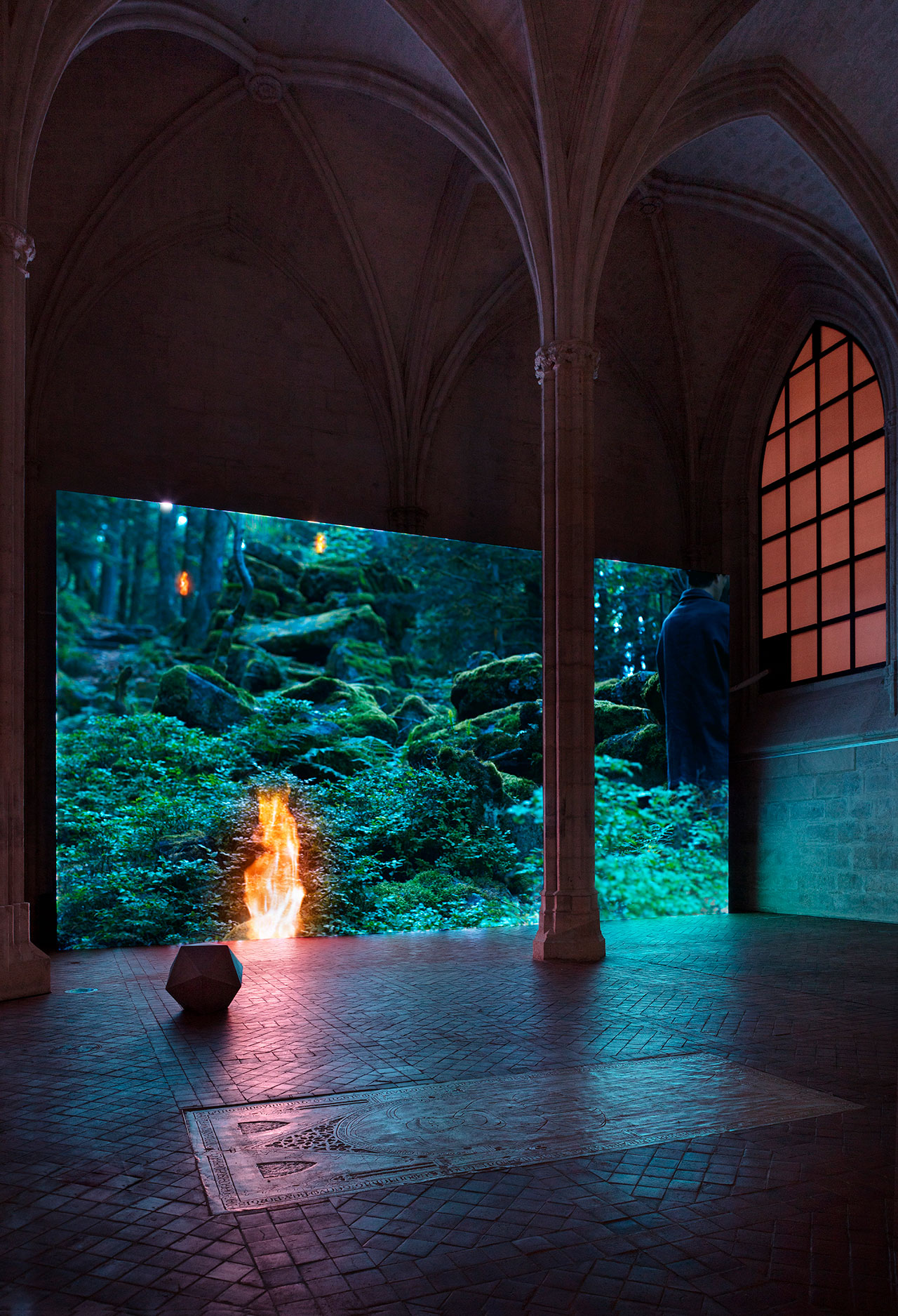

Installation view of Laurent Grasso's exhibition ANIMA at Collège des Bernardins, Paris, 2022. Photo Tanguy Beurdeley © Laurent Grasso - ADAGP, Paris 2022. Courtesy Perrotin.

Installation view of Laurent Grasso's exhibition ANIMA at Collège des Bernardins, Paris, 2022. Photo Tanguy Beurdeley © Laurent Grasso - ADAGP, Paris 2022. Courtesy Perrotin.

Laurent Grasso, Anima, film HR (in progress) © Laurent Grasso / ADAGP, Paris, 2022. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

Laurent Grasso, Anima, film HR (in progress) © Laurent Grasso / ADAGP, Paris, 2022. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

Intrigued by the confluence of geological, mythological and spiritual forces, Grasso researched the history of the area in collaboration with historian Grégory Quenet, and “Anima” is the artistic outcome of this process. Filmed in Mont Sainte-Odile, the film mixes the perspectives and points of view of different protagonists - a man, a fox, rocks - populating a mysterious world that hovers in-between reality and dreams with mystical elements like suspended flames, ghostly clouds, and even a ‘pyrophone’, a 19th century music instrument in which notes are produced by mini explosions taking place inside a series of glass tubes.

Choreographed camera movements, illusory images made with a LIDAR scanner, ethereal lighting and an esoteric soundtrack by Warren Ellis plunge spectators into a mysterious atmosphere where the invisible part of the world becomes visible. Shown on a colossal LED screen in the College des Bernardins’ former sacristy, the film’s hypnotic power is enhanced by the space’s meditative quality and cavernous grandeur, while bespoke marble stools inspired by Plato and Archimedes’ polyhedrons add another layer of symbolic references. The film’s mystical phenomena continue in the nave, this time in a series of paintings that are interwoven with the building’s architecture, both spatially and conceptually.

Installation view of Laurent Grasso's exhibition ANIMA at Collège des Bernardins, Paris, 2022. Photo Tanguy Beurdeley © Laurent Grasso - ADAGP, Paris 2022. Courtesy Perrotin.

Laurent Grasso, Anima, film HR (in progress) © Laurent Grasso / ADAGP, Paris, 2022. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

Installation view of Laurent Grasso's exhibition ANIMA at Collège des Bernardins, Paris, 2022. Photo Tanguy Beurdeley © Laurent Grasso - ADAGP, Paris 2022. Courtesy Perrotin.

Installation view of Laurent Grasso's exhibition ANIMA at Collège des Bernardins, Paris, 2022. Photo Tanguy Beurdeley © Laurent Grasso - ADAGP, Paris 2022. Courtesy Perrotin.

Laurent Grasso, Studies into the Past. Oil on wood, 84 x 84 cm (framed) © Laurent Grasso / ADAGP, Paris, 2022. Photo: Tanguy Beurdeley. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin Laurent.

Established in the 13th century as a place of study and research, less than one half-century after the creation of the University of Paris, the building was converted into a jail, warehouse, fire station and Police Academy in the 19th and 20th centuries before opening its doors again in 2008 as a cultural centre. Throughout the centuries, the immense nave, which was modelled on the architecture of Cistercian abbeys, remained the centre of its educational, social and religious life. A paradigm of sobriety and refinement, the 70-metre-long, 6-metre-high space features a forest of 32 slender columns supporting beautiful groin vaults. Once partitioned into classrooms, a refectory, chapter and kitchen, the space was unified in 2004, its true magnificence finally revealed. It’s no wonder then that the building’s Gothic interiors found its way into Grasso’s paintings.

Painted in the style of Italian and Flemish painters of the 15th and 16th centuries like Fra Angelico, Sandro Botticelli and Pieter Bruegel the Elder the oil on wood paintings that Grasso created for the exhibition are a continuation of the series Studies Into the Past that the artist begun in 2009. In the series, faithfully reproduced mythological, religious and historic settings are interrupted by foreign objects and phenomena like eclipses, meteorites and spheres in order to upend our perception of the past. In this case, the Collège des Bernardins-inspired vaulted architecture is invaded by clouds, fires and levitating rocks, all recurring figures in the artist’s work, including the Anima film.

Laurent Grasso, Studies into the Past. Oil on wood, 84 x 84 cm (framed) © Laurent Grasso / ADAGP, Paris, 2022. Photo: Tanguy Beurdeley. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin Laurent.

Installation view of Laurent Grasso's exhibition ANIMA at Collège des Bernardins, Paris, 2022. Photo Tanguy Beurdeley © Laurent Grasso - ADAGP, Paris 2022. Courtesy Perrotin.

Installation view of Laurent Grasso's exhibition ANIMA at Collège des Bernardins, Paris, 2022. Photo Tanguy Beurdeley © Laurent Grasso - ADAGP, Paris 2022. Courtesy Perrotin.

Installation view of Laurent Grasso's exhibition ANIMA at Collège des Bernardins, Paris, 2022. Photo Tanguy Beurdeley © Laurent Grasso - ADAGP, Paris 2022. Courtesy Perrotin.

A meditation on time, the series aims to “create spaces that [suggest] another temporality”. In fact, Grasso takes pains to accurately create the historical paintings in collaboration with conservationists in order to achieve what he calls a “false historical memory,” so that in the distant future it will be impossible to identify the period when the works were created.

Fixed on the nave’s columns, not unlike the funerary coats of arms traditionally placed on the pillars of churches, the paintings on display constitute a type of mise-en-abyme, a formal technique of the Western art canon whereby a copy of an image is placed within itself. But whereas Old Masters like Velázquez applied the technique inside the confines of the canvas, Grasso expands the idea to three dimensions, making the architecture of the space part of the experience.

Installation view of Laurent Grasso's exhibition ANIMA at Collège des Bernardins, Paris, 2022. Photo Tanguy Beurdeley © Laurent Grasso - ADAGP, Paris 2022. Courtesy Perrotin.

Installation view of Laurent Grasso's exhibition ANIMA at Collège des Bernardins, Paris, 2022. Photo Tanguy Beurdeley © Laurent Grasso - ADAGP, Paris 2022. Courtesy Perrotin.

Installation view of Laurent Grasso's exhibition ANIMA at Collège des Bernardins, Paris, 2022. Photo Tanguy Beurdeley © Laurent Grasso - ADAGP, Paris 2022. Courtesy Perrotin.

Installation view of Laurent Grasso's exhibition ANIMA at Collège des Bernardins, Paris, 2022. Photo Tanguy Beurdeley © Laurent Grasso - ADAGP, Paris 2022. Courtesy Perrotin.

Laurent Grasso, Untitled, 2022 (in progress). Bronze. Photo Stefano Baroni. © Laurent Grasso / ADAGP, Paris, 2022. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin

Completing the installation are a series of sculptures on the nave’s walls that explore the concept of vision. Featuring tree-like forms with eyes growing out of their bare branches instead of leaves, the bronze Panoptes (2021) references the religious iconography of Saint Odile who is depicted holding a book with two eyes on it as a symbol of her miraculously regained eyesight, as well as Saint Lucia who Renaissance artist Francesco del Cossa painted holding a stem with two eyes. An illuminated version made out of neon tubes further amplifies the effect. Even more unsettling, Untitled (2022), a large soot-coloured rock punctuated by seven illuminated eyes, is an allusion to one of the eight visions of Zechariah from the Old Testament. Surreal and ambiguous, yet not entirely out of the realm of possibility, Grasso’s installation intuitively blends the past, present and future inevitably forcing visitors to question what they thought they knew.

Installation view of Laurent Grasso's exhibition ANIMA at Collège des Bernardins, Paris, 2022. Photo Tanguy Beurdeley © Laurent Grasso - ADAGP, Paris 2022. Courtesy Perrotin.

Installation view of Laurent Grasso's exhibition ANIMA at Collège des Bernardins, Paris, 2022. Photo Tanguy Beurdeley © Laurent Grasso - ADAGP, Paris 2022. Courtesy Perrotin.

Laurent Grasso, Panoptes, 2021. Bronze, 65 x 50 x 11cm. Photo Claire Dorn © Laurent Grasso / ADAGP, Paris, 2022 Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin

Installation view of Laurent Grasso's exhibition ANIMA at Collège des Bernardins, Paris, 2022. Photo Tanguy Beurdeley © Laurent Grasso - ADAGP, Paris 2022. Courtesy Perrotin.

Installation view of Laurent Grasso's exhibition ANIMA at Collège des Bernardins, Paris, 2022. Photo Tanguy Beurdeley © Laurent Grasso - ADAGP, Paris 2022. Courtesy Perrotin.