Kostas Lambridis, Elemental Cabinet. Photo courtesy Carpenters Workshop Gallery.

Kostas Lambridis, Elemental Cabinet. Photo courtesy Carpenters Workshop Gallery.

Kostas Lambridis, Elemental Cabinet (detail). Photo courtesy Carpenters Workshop Gallery.

Commissioned by Henry Somerset, the 3rd Duke of Beaufort, for his Palladian home when he was just 19 years of age, the ebony, bronze-gilded Badminton Cabinet is adorned by elaborate mosaics in pietra dura and bedazzled in a wealth of gemstones sourced from around the world, from lapis lazuli, agate and green jasper, to chalcedony and amethyst quart. It was designed in other words as the ultimate status symbol. Lambridis has mixed feeling about the ostentatious heirloom, “I both admire it and loath it” he says. It may be humbling in its baroque grandeur but nowadays it seems obscene in its vainglorious championship of class and wealth.

In this sense, his replica is one of both homage and subversion; although it adheres to the original’s shape and size – the result of a 3-D scan which Lambridis conducted at Vienna’s Palais Liechenstein where Badminton Cabinet is displayed – it radically redefines and reconstructs its constituent parts by rejecting the traditional hierarchical view of materials in favour of a level playing field. For Lambridis “there’s no such thing as ‘better’ material” as Robert Rauschenberg said. Artistically the value of gold and ebony is exactly the same as that of aluminium and fibreboard, so by using humble materials and found objects he’s attempting to re-calibrate values and principles long held sacrosanct in the design world and our culture at large.

Kostas Lambridis, Elemental Cabinet (detail). Photo courtesy Carpenters Workshop Gallery.

Kostas Lambridis, Elemental Cabinet (detail). Photo courtesy Carpenters Workshop Gallery.

Kostas Lambridis, Elemental Cabinet (detail). Photo courtesy Carpenters Workshop Gallery.

Kostas Lambridis, Elemental Cabinet (detail). Photo courtesy Carpenters Workshop Gallery.

Kostas Lambridis, Elemental Cabinet (detail). Photo courtesy Carpenters Workshop Gallery.

At first glance, the Elemental Cabinet appears like a chaotic assemblage of mismatched parts, an absurd concoction you might have conjured in a dream rather than stumble upon in a gallery. And yet, its haphazard appearance belies a finely tuned, rational blueprint unfolding in two axes where every component has its rightful place. Vertically, the materials have been arranged in five strata from the heavier at the bottom to the lighter on top: chunks of concrete, stone and ceramics at the base give way to metals, then layers of wood, plastics, and finally textiles and recycled electronics which make up the cabinet’s functioning clock, beautifully embroidered by the artist’s mother – she also makes delicious pastries which supply the studio with a much needed source of energy.

Whereas vertically the materials are distributed according to their weight – which is the proper way to value materials according to late Greek sculptor Jannis Kounellis, Lambridis points out – horizontally they are arranged according to their treatment: materials on the left side have been highly crafted while those on the right are incorporated in their natural, raw state. And there’s more, while the front of the cabinet respects the compositional design of the original design, the back exposes the artist’s sui generis construction methods, incorporating, for example, the moulds and casts that were used to craft the façade. The tentative balance between the cabinet’s apparent chaos and ingrained order goes to the heart of Lambridis’ artistic sensibility which explores the elemental human struggle between entropy – the tendency of letting go, to surrender to our eventual demise – and achieving greatness, conquering mortality in other words.

Kostas Lambridis, Elemental Cabinet. Photo courtesy Carpenters Workshop Gallery.

Kostas Lambridis, Elemental Cabinet. Photo courtesy Carpenters Workshop Gallery.

Kostas Lambridis portrait. Photo © Edouard Caupeil

Kostas Lambridis, Elemental Chandelier. Photo courtesy Carpenters Workshop Gallery.

Kostas Lambridis, Elemental Chandelier. Photo courtesy Carpenters Workshop Gallery.

Kostas Lambridis, Elemental Chandelier. Photo courtesy Carpenters Workshop Gallery.

Lambridis’ extraordinary cabinet was followed by two additional pieces that share his conceptual rigour and non-hierarchical approach to design. Continuing his polemic against elitism, an Elemental Daybed and Elemental Chandelier are also archetypal symbols of luxury, privilege and wealth, but whereas the cabinet was conceived as the antithesis of Baroque, they were conceived as a critique on modernism. What’s more, instead of replicating a particular piece of design, they draw from multiple works from iconic designers such as Charles and Ray Eames, Robert Rauschenberg, Marc Newson and the Campana Brothers.

After the specificity of the Badminton Cabinet, such diverse sources of inspiration allude, as Lambridis explains, to a longing for more creative freedom. Thus, the pieces he’s currently working on eschew any design references, exploring instead the properties of the principal materials he’s using: stone, concrete, plaster, glass and ceramics. Lambridis is very adamant about his “egalitarian” approach to materials. “I don’t care if what I’m working with was found in the garbage or if it cost 1000 Euros”, he says, “I treat them with the same respect – or lack of respect”. In practice, this means that everything around him can potentially be incorporated into his work which is both liberating and bewildering he admits.

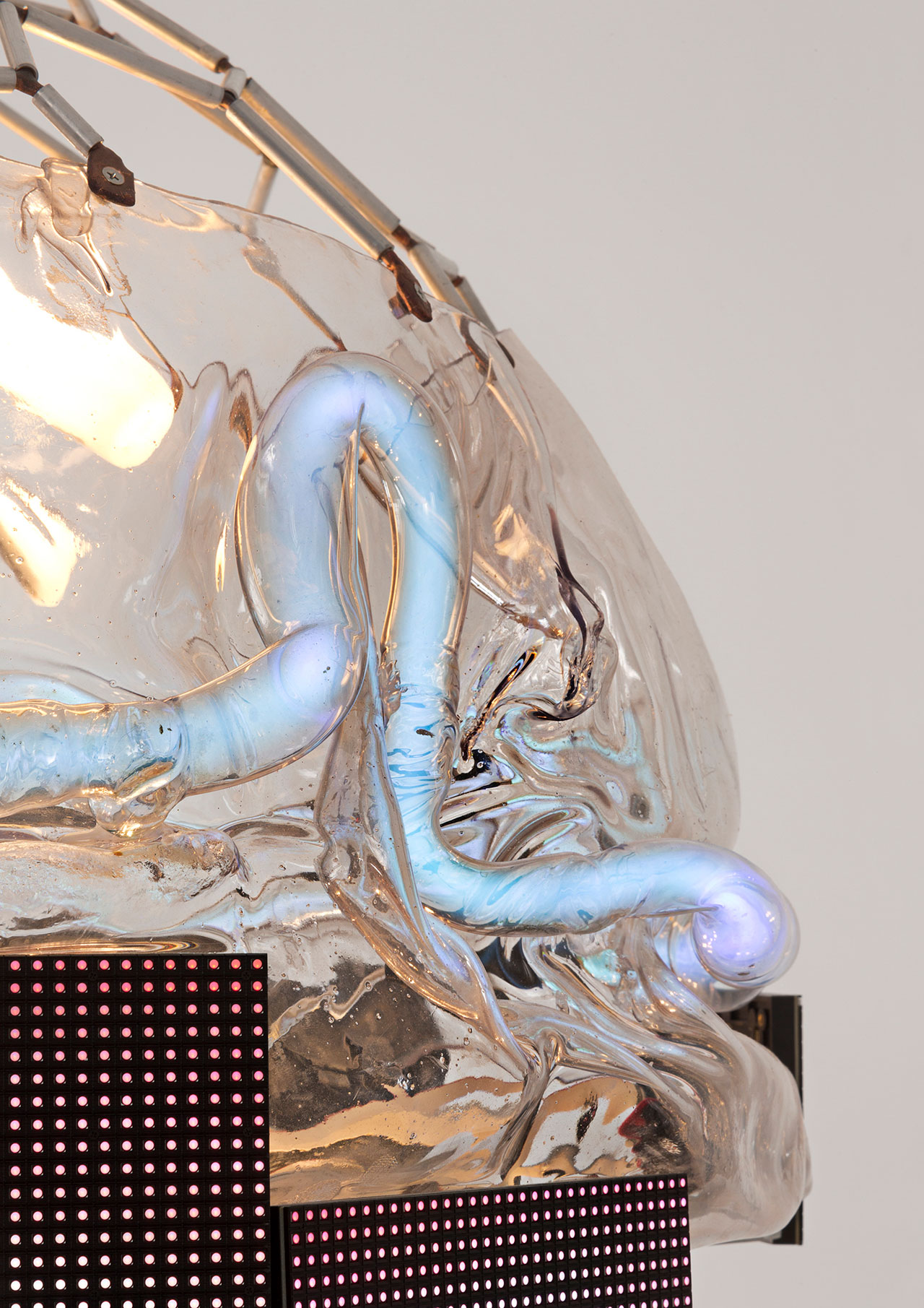

Kostas Lambridis, Elemental Chandelier (detail). Photo courtesy Carpenters Workshop Gallery.

Kostas Lambridis, Elemental Daybed. Photo courtesy Carpenters Workshop Gallery.

Kostas Lambridis, Elemental Daybed. Photo courtesy Carpenters Workshop Gallery.

Kostas Lambridis, Elemental Daybed. Photo courtesy Carpenters Workshop Gallery.

Such an inclusive approach when it comes to materials poses the risk though of not knowing when is the right time to stop working on a design, which Lambridis confesses is a real challenge – even now, two years after the cabinet’s construction, and after some rejigging, it doesn’t feel complete he admits. This is where Aristotle and his concept of "phronesis" comes in, which Lambridis talks about with enthusiasm. Phronesis is the practical wisdom of knowing when to be bold and when not to, when to advance and when to step back. Practical or not, Lambridis is definitely boldly advancing at the moment, working on new works and looking forward to an exciting future, as he should.

Kostas Lambridis, Elemental Daybed. Photo courtesy Carpenters Workshop Gallery.

Kostas Lambridis, Elemental Daybed (detail). Photo courtesy Carpenters Workshop Gallery.

Kostas Lambridis, Elemental Daybed (detail). Photo courtesy Carpenters Workshop Gallery.

Kostas Lambridis, Elemental Daybed. Photo courtesy Carpenters Workshop Gallery.

Kostas Lambridis portrait. Photo © Edouard Caupeil