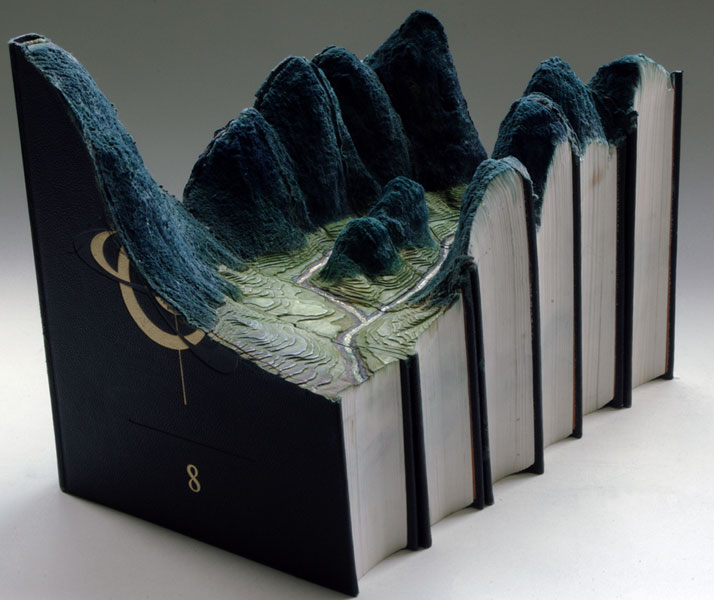

Grand Larousse (2010)

photo © Guy Laramée

The human spirit transcends the known through the work of Guy Laramée the Montreal based artist who pushes the materiality of the common book to the limit. Continuing the lines drawn by Caspar Friedrich and Gerhard Richter, Laramée admits to his attraction to spirituality. He combines the old philosophies of Asian arts and Zen and draws energy from Romanticism. Yatzer caught up with the artist to discover his approaches to his practice and discussed human primitiveness, sand-blasting and artistic freedom...

Grand Larousse (2010), detail

photo © Guy Laramée

Do you class yourself as a romantic and if so, in which ways?

As most artists, I try to transcend all identifications. I always refer to these words from Kabir as my motto: ''If you were to free me, free me from myself''. So if I was to accept seeing myself as a 'Romantic', it would only be provisional. On the other hand however, over the last few years, I have come to question our cult of innovation and sought to reconcile myself with what we call 'tradition' (for lack of a better word). As much as I seek to accept discontinuity, to welcome it, not so much as a modus vivendi- having to break from the past – but rather as a fact, I also want to find what lies behind impermanence. So gradually, I had my ''coming out'' so to speak, and I became less and less reluctant to confess that yes, if I find a link in any current of art history, it is probably Romanticism that best describes my preoccupations as an artist. It is Gerhard Richter who sort of gave me the rubber stamp to accept that as much as we want to find our way, outside history, we also have the task of pursuing the lines of work drawn by our ancestors. Not any line, not all the lines, but those that we feel must be continued.

So in a way my work is about continuing this line that goes From Caspar Friedrich to Gerhard Richter. Of course ''Romanticism'' is in itself a big movement and I don’t claim to defend all of its tenants. Of all the descriptors one finds about this current, it is probably the most understated that attracts me the most: spirituality. The way the Romantics sought to see the transcendent in nature finds echoes in the Asian arts that were linked to Chan’ – the ancestor of Zen. I can identify with that easily. I had what religious literature refers to as ''epiphanies'' while climbing high mountains. I think one reason why this kind of sensibility is now dismissed in contemporary art is simply this: people don’t go there. So if you don’t experience the ''Sublime'' first hand, the next step is to deny its existence.

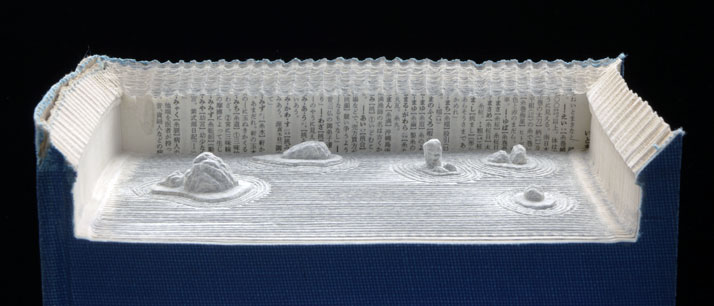

photo © Guy Laramée

Themes such as isolation, spirituality and the greatness of nature are ever present. Can you expand on the importance of these themes?

My work is not about nature. It is about the feelings that a wild setting triggers. It is about transcending the mundane. Going beyond both the known and the unknown and heading for the unknowable. I think it is Christianity that had us thinking about the ''transcendent'' as a floating realm, outside this world, a paradise of sorts. Asian spiritualities give a completely different reading of the term. To them the concept of ''transcendence'' means simply beyond, beyond opposites, beyond concepts, concepts of any kind, even the concept of ''concept''. So in a way, I am closer to people like Agnes Martin, who found a way of going beyond the mundane through abstraction. ''Painting is not about ideas or personal emotions'' she said. ''Paintings are about being free from the cares of the world, free from worldliness''.

Talk us through your creative process with one or two examples.

Inspiration is a very mysterious thing. It comes unexpectedly. Of course, having baked some preoccupations for more than thirty years now – questioning the ideologies of progress, being nurtured by non-western cultures, rooting myself in the existential and the meaning of suffering, questioning our fascination for the accumulation of knowledge, etc – it is normal that inspiration would come in the guise of these questionings. The book is a good example. It came out very casually. Whilst working on a sculpture in a metal shop, I looked over to a sandblaster cabinet that I used occasionally and thought to myself ''what would it be like to put a book in there?'' And there it was. In seconds, the whole thing bloomed. I saw the landscape and the whole line of work actually. But many discoveries go unattended, for lack of proper ground. I think the reason why I picked up this thread so readily is that at the time, I was doing a master in anthropology. (I was actually doing two master degrees simultaneously - another one in visual arts.) So this discovery – sandblasting books – just gave form to my ambiguous relation to academia and to knowledge in general. For years I had been questioning this need that we have to pile things into our head. Wisdom, I thought, must be the exact opposite: emptying one’s certitudes, instead of building them. Or rather founding another ground to certitude than sheer belief –our so-called sciences, what I call the ''religions of the objective''.

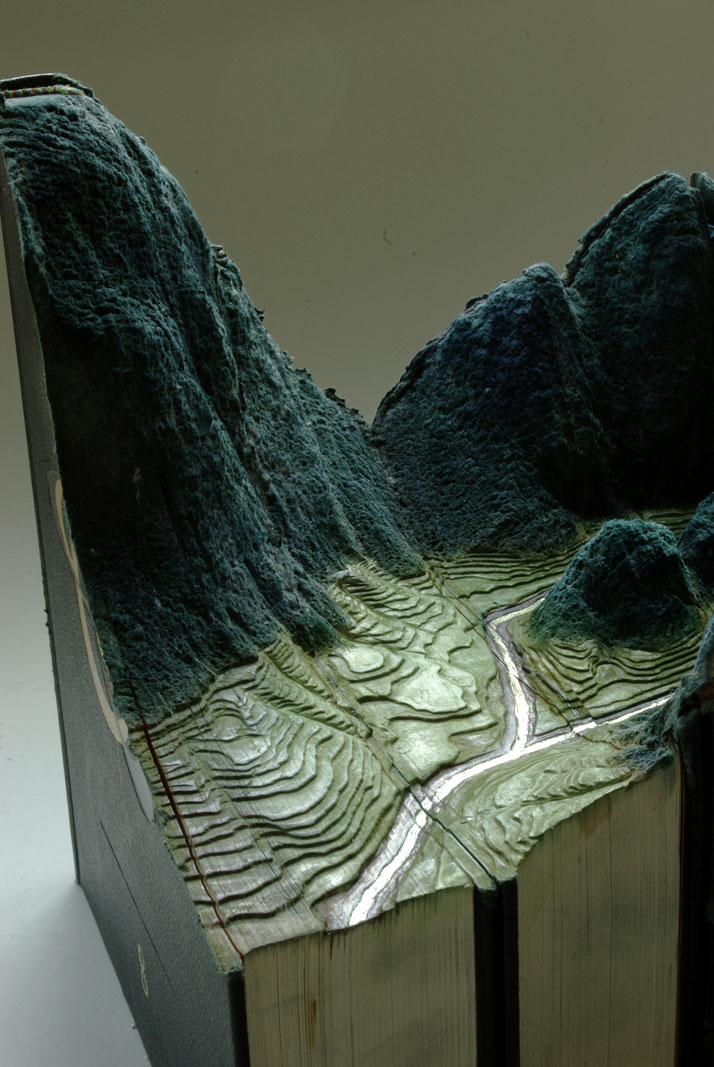

Historia das americas (2009)

photo © Guy Laramée

photo © Guy Laramée

Why books? Would you say that you treat books as traces of civilization?

Yeah, why books… Certainly traces, but not so much of civilizations as traces of how our minds work. I’m looking for an outside to the intellect – as most artists certainly do, most of which is achieved without knowing. The mind is inescapable. We can’t stop thinking, even if we try to. But we can take a step backward and see it for what it is: a dream within a dream. That itself is liberation. And what do artists seek, if not their freedom?

Is a sculptural intervention on any specific book determined by the book's content?

I am not interested in what lies inside those books. I do not comment on their content. I want to shift our focus from ''what we think'' to ''THAT we think''. At first I restricted myself only to encyclopaedias and dictionaries. It was easier in a way as there are so many books! I was attracted to encyclopaedias because of their alleged neutrality. Encyclopaedias were also becoming the locus of obsolescence. I could find them for $0.25 a book and that was because they were no longer valid, both in their content as well as being a vehicle for knowledge. But one day I was walking through the aisles of a library and I found one book, the only book in years that drew my attention not because of its title. You know, when you look at books, what do you look at? The title, the author, in brief: the function. But this book was just…beautiful! The colour of the cover, the nickel tone of it embossed title, everything was perfect. I stole it! Of course I found a replacement copy – which cost me $250… but anyway, this became my fetish. I then walked into libraries and bookstores, not looking at content, but looking at form. I had found another way, a more ''clever'' way, to deny content.

So now I go by gut feeling. The book throws a feeling, not even an image at me, and then the image comes, most often all of a sudden. And most of the times, I find afterwards that that image is a perfect response to one of my life’s dilemmas. Last week, one of my books that was badly shelved had become misshapen somewhat. My first reaction was to put it under other books to press it, so that it would recover its “correct” shape. Then all of a sudden this image of a wave, a tsunami came to me, and there it was: the best vehicle to convey all the emotions that the last tsunami in Japan had triggered in me.

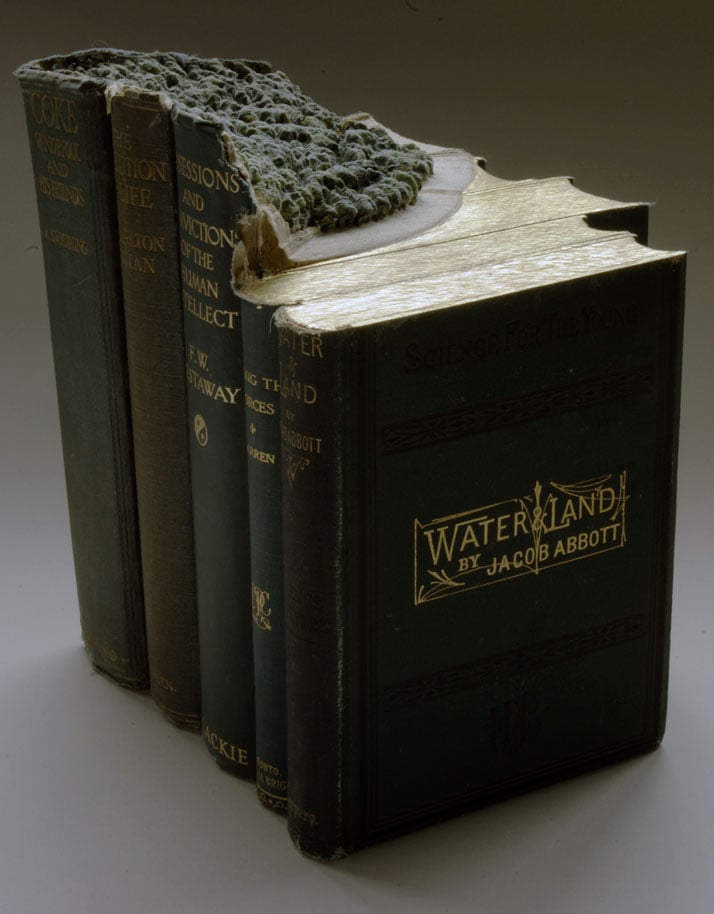

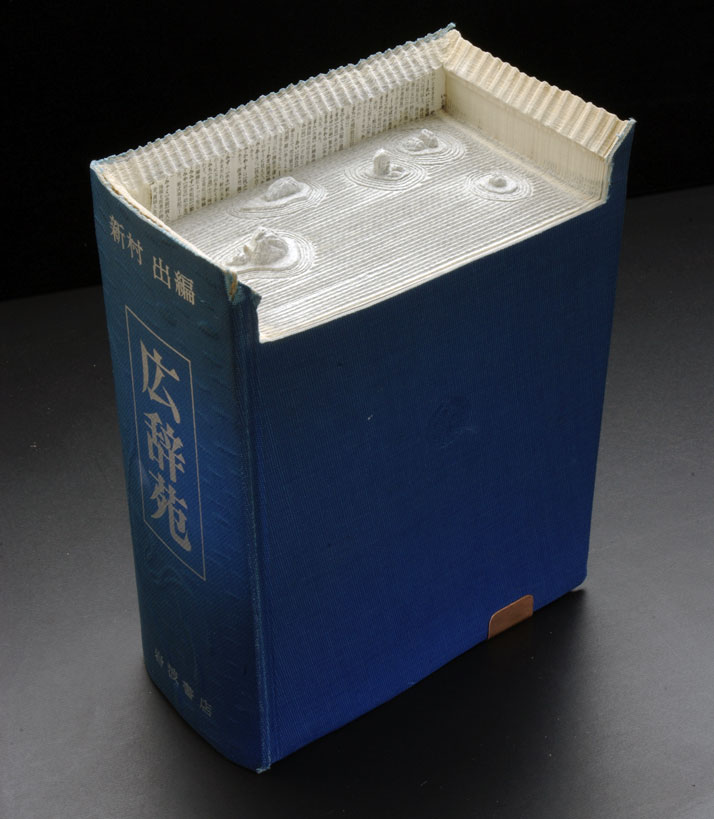

Ryoanji (2010), detail

photo © Guy Laramée

Ryoanji (2010), detail

photo © Guy Laramée

Ryoanji (2010)

photo © Guy Laramée

Do you use new technological processes? If so how do you reason their use when dealing with such a romantic concept?

No laser, no computer, just plain standard manual electric tools that wood carvers use. From band saw to chain saw to grinder to flexible shaft rotary tools – all very standard procedure for any sculptor. You see, I don’t abide by any moral prescriptions. I don’t see Romanticism as forbidding as much as allowing. It allows one to trust one’s own feelings, one’s intuitions – whatever that means, one’s own relations to perceptions and yes, sometimes, concepts.

How is human primitiveness discussed through your work?

I think humans have not evolved much since cavemen. And that is good news. The Zen master Robert Aitken said in substance that it is though the old that we touch the timeless, that which is beyond the old and new. Of course that being said, our consciousness has evolved. We are far more conceptual than our ancestors. They were centred on the Idol and the temple whereas we are centred on the 'I'. My work questions this centre, the 'I' through a simple and very old device: contemplation. Again this word has suffered the necessity of language. It is common to hear people say that they are 'contemplating something'. But if you abide to the original meaning of the word, that is impossible. You cannot contemplate something because contemplation is precisely about abolishing the distance between the viewer and the view. The magic of the small worlds and the misty landscape in my painting all call for a different relation to the world. They are an invitation to enter and lose oneself in the spectacle.

Is there any reason why the human figure is absent in your work?

It is not absent, not even for a second! YOU are always there. YOU are always in the picture!

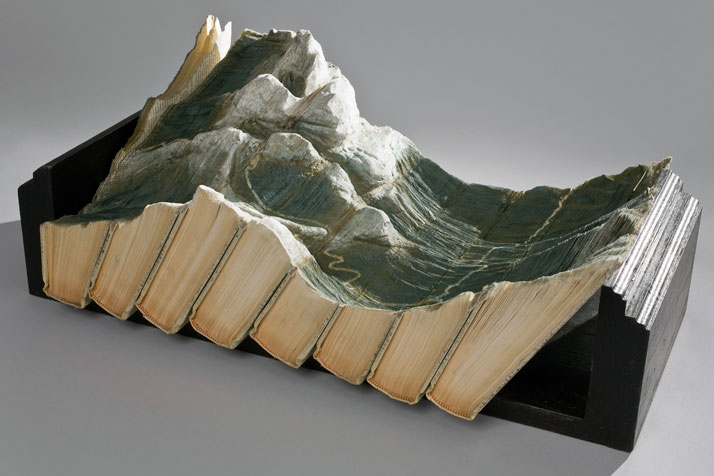

Tectonic

photo © Guy Laramée

The Grand Library

photo © Guy Laramée

The Grand Library, detail

photo © Guy Laramée

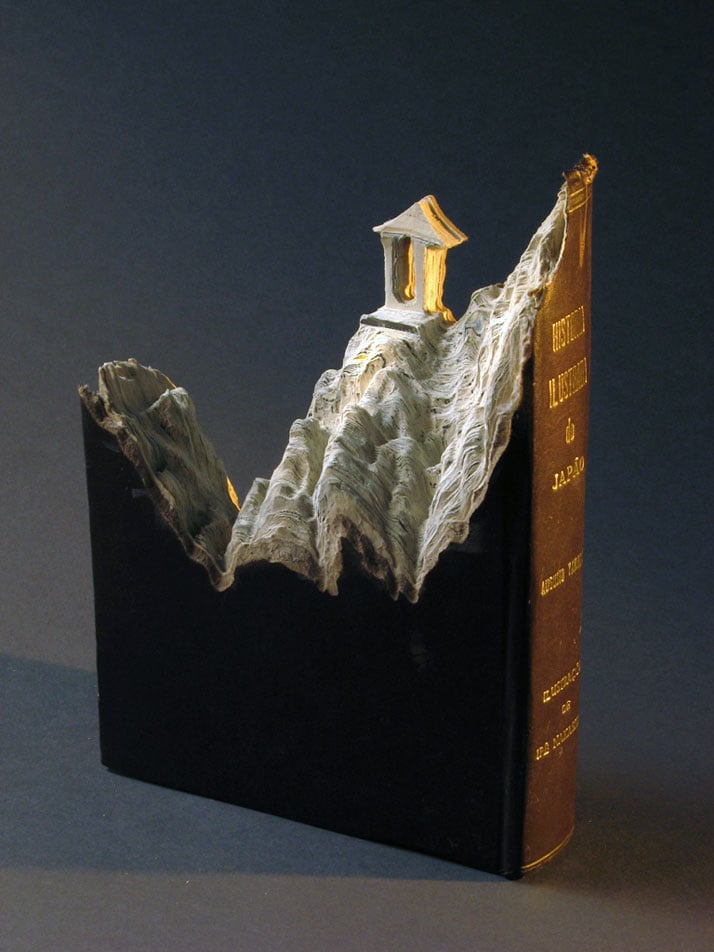

Illustrated History of Japan

photo © Guy Laramée

photo © Guy Laramée

photo © Guy Laramée