| Detailed Information | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Project Name | Matt Shlian talks to Yatzer | Posted in | Drawing, Sculpture, Interview | Artist | Matt Shlian |

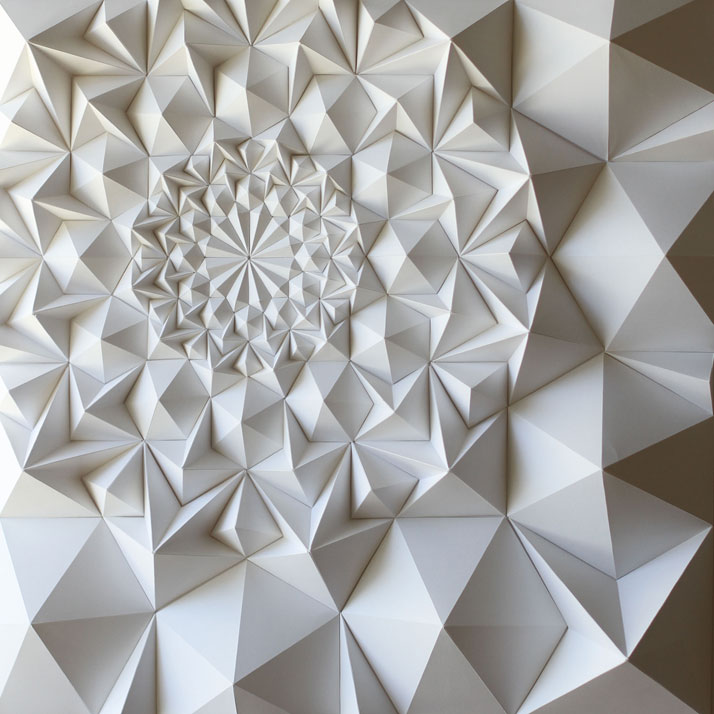

When You Are Killing what You Are Meant to Kill there Can Be no Remorse, 2012; tyvek, size varies. Photo by Josh Kurz.

Ara 114 (detail), 2012; paper 19 x 25 x 2 inches. Photo courtesy of Matt Shlian.

Ara 103, 2011; paper 8 1/2 x 11 x 1/2 inches. Photo courtesy of Matt Shlian.

ALEATORIC 3 (detail), 2012; paper 11 x 15 x 1 1/2 inches. Photo by Cullen Stephenson.

Shlian for Levi's, 2012; paper 14 x 8 feet. Photo courtesy of the artist.

ALEATORIC 3 (detail), 2012; paper 11 x 15 x 1 1/2 inches. Photo by Cullen Stephenson.

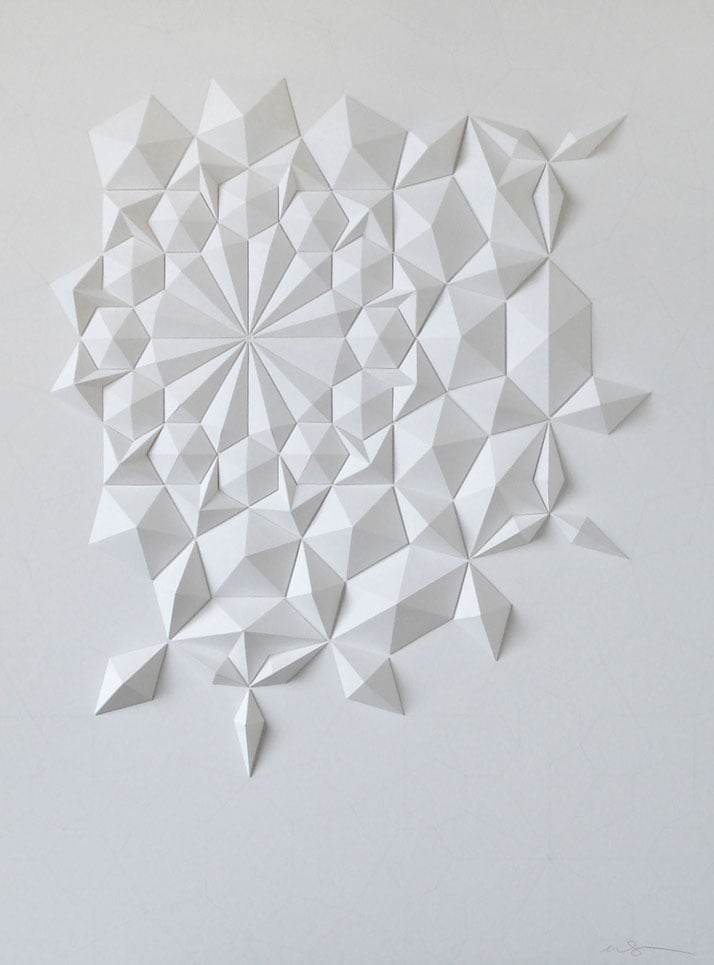

ALEATORIC 1, 2012; paper 11 x 15 x 1 1/2 inches. Photo by Cullen Stephenson.

117 apo, 2013; paper 19 x 40 x 1/2 inches. Photo courtesy of Matt Shlian.

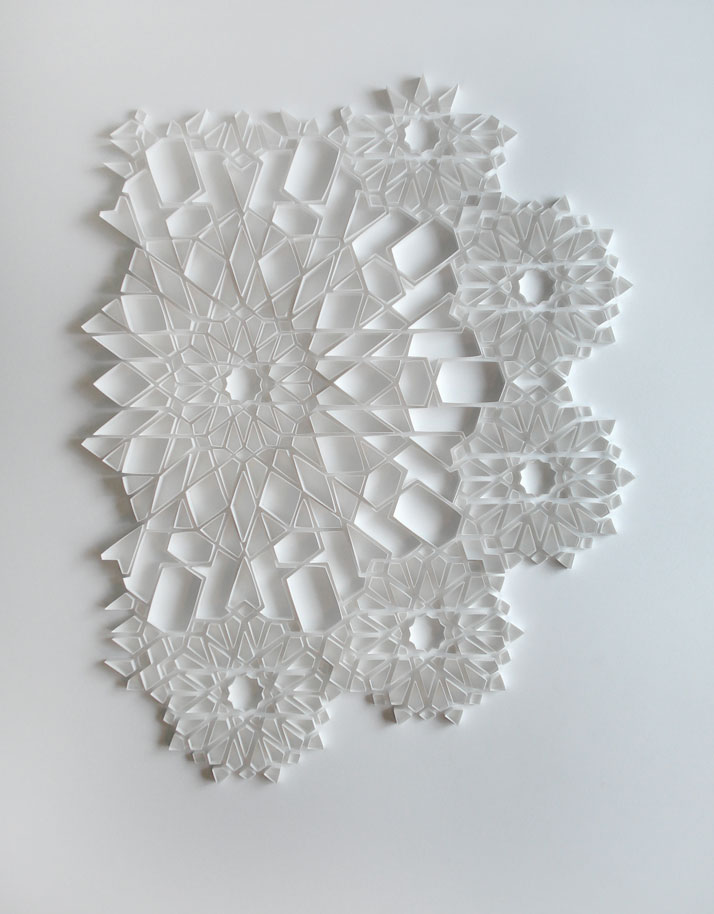

Tesselation Series, 2011; paper 8 1/2 x 11 x 1/2 inches. Photo courtesy of Matt Shlian.

Matt Shlian’s proclivity for both geometry and paper has defined his craft, with drawings, prints and sculpture that are unique in their manifestation. Shlian works out of his design studio based in Ann Arbor, home to the University of Michigan where he also teaches; he is also involved in a U.S. National Science Foundation funded research campaign at the university, working alongside engineers to discover if origami, the traditional Japanese art of paper folding, can provide a foundation for three-dimensional nanotechnology. Further to this, Shlian has an extensive client list, including Apple, Facebook, Levi’s and Sesame Street. His current exhibition, ''Stacked & Folded Paper as Sculpture'' at The Dennos Museum Center in Northwestern Michigan College, is a joint presentation with Chinese artist Li Hongbo (whose work has featured previously on Yatzer). The exhibit is an East meets West showcase of approaches to using paper as a means of creating sculpture.

As an artist, Matt Shlian is both unconventional and curious. He’s an explorer, an inventor, and is unorthodox and refreshingly ''anti-glitter''. He has a way of ''misunderstanding'' the world that helps him to see things that can be easily overlooked. Something of an enigma, Yatzer asked Matt to explain his work further:

At what point did you consider yourself to be a paper engineer?

I began using the title ‘paper engineer’ after I had worked in the industry for several years, focusing on paper as a medium.

Through the use of origami, you’re offering engineers the chance to consider their work in three dimensions. But how do you make the connection - how do you understand or know what it is they are looking for?

My team and I work closely together and although we don’t always speak the same language, our work - the transformation of two-dimensional materials into three-dimensional forms - unites us. It is typically the case that we are not entirely certain about what it is we are looking for at the outset. On a recent occasion, one of the scientists told me that when we first met it was as though I had this big box of solutions and it was their job to figure out which questions were best solved with my work [three-dimensional origami]. I thought this was both an amiable compliment and a good way to describe the process.

My sense is that you are not an artist in the conventional (perhaps restrictive) view of the word. How does someone who originally went to school to study ceramics find his way to working within the field of nanotechnology?

It is not a linear or logical path, rather I followed the work. My interest in geometric form led me to paper - then paper led me to pop-up books. Mechanical movement in paper engineering led me to architecture and design, which in turn led to my collaborating with people outside of the art world. The definition of artist is shifting - people who think that the artist works alone, wearing a beret and painting all day, are mistaken in this notion. It takes a lot of resourcefulness to succeed as an artist. Someone close to me once joked that it took me ten years to become an overnight sensation.

4 days in August, 2010; paper 19 x 25 x 1/2 inches. Photo courtesy of Matt Shlian.

Ara 142, 2014; 18 x 24 x 3/4 inches. Photo courtesy of Matt Shlian.

Ara 117, 2012; folded paper 19 x 25 x 1 inches. Photo courtesy of Matt Shlian.

4 days in Jordan, 2011; paper 8 x 8 x 1/2 inches. Photo courtesy of Matt Shlian.

ORBIT (detail), from Process Series 2, 2013; paper 8 x 11 x 1/2 inches. Photo by Cullen Stephenson.

WAVE (detail), from Process Series 2, 2013; paper 8 x 11 x 1/2 inches. Photo by Cullen Stephenson.

WAVE, from Process Series 2, 2013; paper 8 x 11 x 1/2 inches. Photo by Cullen Stephenson.

ORBIT, from Process Series 2, 2013; paper 8 x 11 x 1/2 inches. Photo by Cullen Stephenson.

Sleeper, 2013; paper 8 1/4 x 8 1/4 x 1/4 inches. Photo courtesy of Matt Shlian.

The idea of scientists and artists collaborating is on the one hand remarkable and on the other perhaps intimidating as each discipline will have a certain amount of prejudice and mistrust of the other. How do you overcome this?

The team I work with is the opposite of prejudice. Real scientists are like real artists. They are always asking questions, always curious and always indiscriminate when seeking both solutions and good questions. I was intimated before I met with the scientists [at the University of Michigan] for the first time, mainly due to the fact that I have literally no scientific background. However I realised that they didn’t know my profession and so it was in fact possible that we could learn from each other. Victor Weisskopf, a professor at MIT [Massachusetts Institute of Technology], wrote in an essay titled ‘Teaching Science’ that: ''In science we must always begin by asking questions, not giving answers. In this way we contribute to the joy of insight. For science is the opposite of knowledge. Science is curiosity.''

Looking at some of your commercial projects, for example your sculptures for Shinola and Levi’s, is there a tangible connection between your work and the respective brands? Does the sculpture represent the brand?

To be honest, not in an obvious sense (mainly due to the fact that I had already created those designs before the brands mentioned contacted me). Nevertheless in a larger sense, I suppose the sculpture might represent the brand. The pieces for Shinola and Levi’s were based on classic tile design principals, born out of years of study using geometry as a basis for patterning. In a way these brands are trying to create a ''classic'' feel.

The pieces are complex but not complicated. I see them as studies in ornamentation rather than decoration, where the unit is as important as the whole and symmetry, proportion, light, shadow and repetition are all considered. It’s the difference between Islamic tile design and a Christmas tree. I am anti-glitter.

You say that your starting point is curiosity and that you have a unique way of ''misunderstanding'' the world that helps you to see the things that are often easily overlooked. It’s a wonderful, somewhat chaotic, artistic disposition and a gift. How does it help, or hinder, your scientific leanings?

It has certainly been an advantage to see things in an indirect way -although it can be infuriating when writing grants or proposals or when fine-tuning things. However, when we begin to hone in on what is important, it’s necessary to approach this from new perspectives.

''Li Hongbo & Matt Shlian: Stacked & Folded Paper as Sculpture'' will be on show at The Dennos Museum Center in Traverse City, Michigan, until 4th January 2015.

Recursive, 2012; paper 36 x 44 x 6 inches. Photo courtesy of Matt Shlian.

Swire, 2013; paper 36 x 52 x 5 inches. Photo courtesy of Matt Shlian.

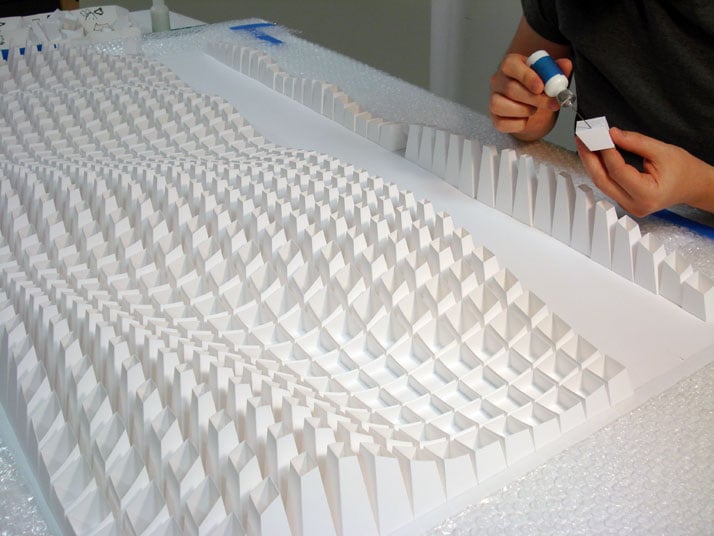

Process of making Swire, 2013; paper 36 x 52 x 5 inches. Photo courtesy of Matt Shlian.

Swire (detail), 2013; paper 36 x 52 x 5 inches. Photo courtesy of Matt Shlian.

FLOAT (detail), from Process Series 2, 2013; paper 8 x 11 x 1/2 inches. Photo by Cullen Stephenson.

We are building this ship as we sail it 1, 2010; folded paper 8 x 6 x 9 inches. Photo courtesy of Matt Shlian.

Extraction 1 White, 2012; paper 12 x 12 x 1 inches. Photo by Cullen Stephenson.

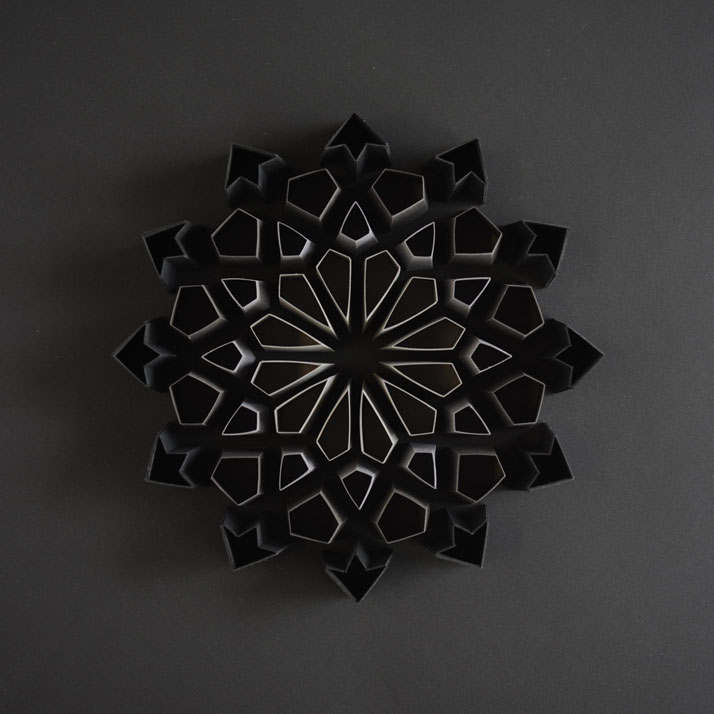

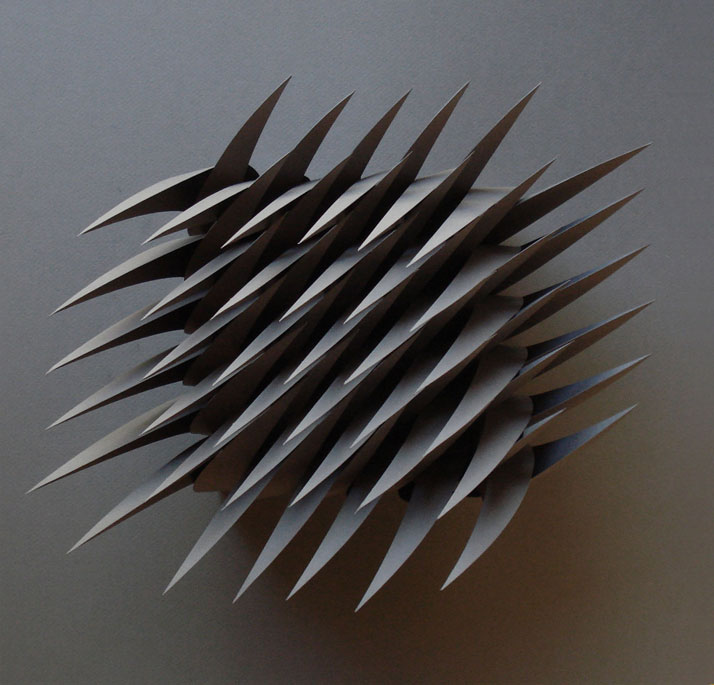

Extraction 2 Black, 2012; paper 12 x 12 x 1 inches. Photo by Cullen Stephenson.

Cursive, 2014; paper 20 x 20 inches. Photo courtesy of Matt Shlian.

Apophenia, 2013; black Strathmore Paper 11 1/4 x 11 1/4 x 1/2 inches. Photos by Cullen Stephenson.