Seeing Poetry: Mexican Artist Jorge Méndez Blake Transforms Literature into Sculpture and Visual Art

Words by Eric David

Location

Seeing Poetry: Mexican Artist Jorge Méndez Blake Transforms Literature into Sculpture and Visual Art

Words by Eric David

Jorge Méndez Blake is a mixed-media, conceptual artist from Guadalajara, Mexico, whose work revolves around books, libraries and literature. An architect by profession, Méndez Blake has evolved a conceptual language, both reductive and metaphorical, that translates literary texts into images, sculptures and installations. Based on his belief that “writing is itself a kind of construction and reading is a way of creation”, he transforms the literary into the spatial thereby giving a physical dimension to the act of reading. His work focuses on the themes classic authors pose through their books, as well as the value of literature as a means of communication and a depository of knowledge; quite fittingly, Mendez Blake produces and catalogues his work in a series of conceptual chapters, each focusing on a different theme, author or approach.

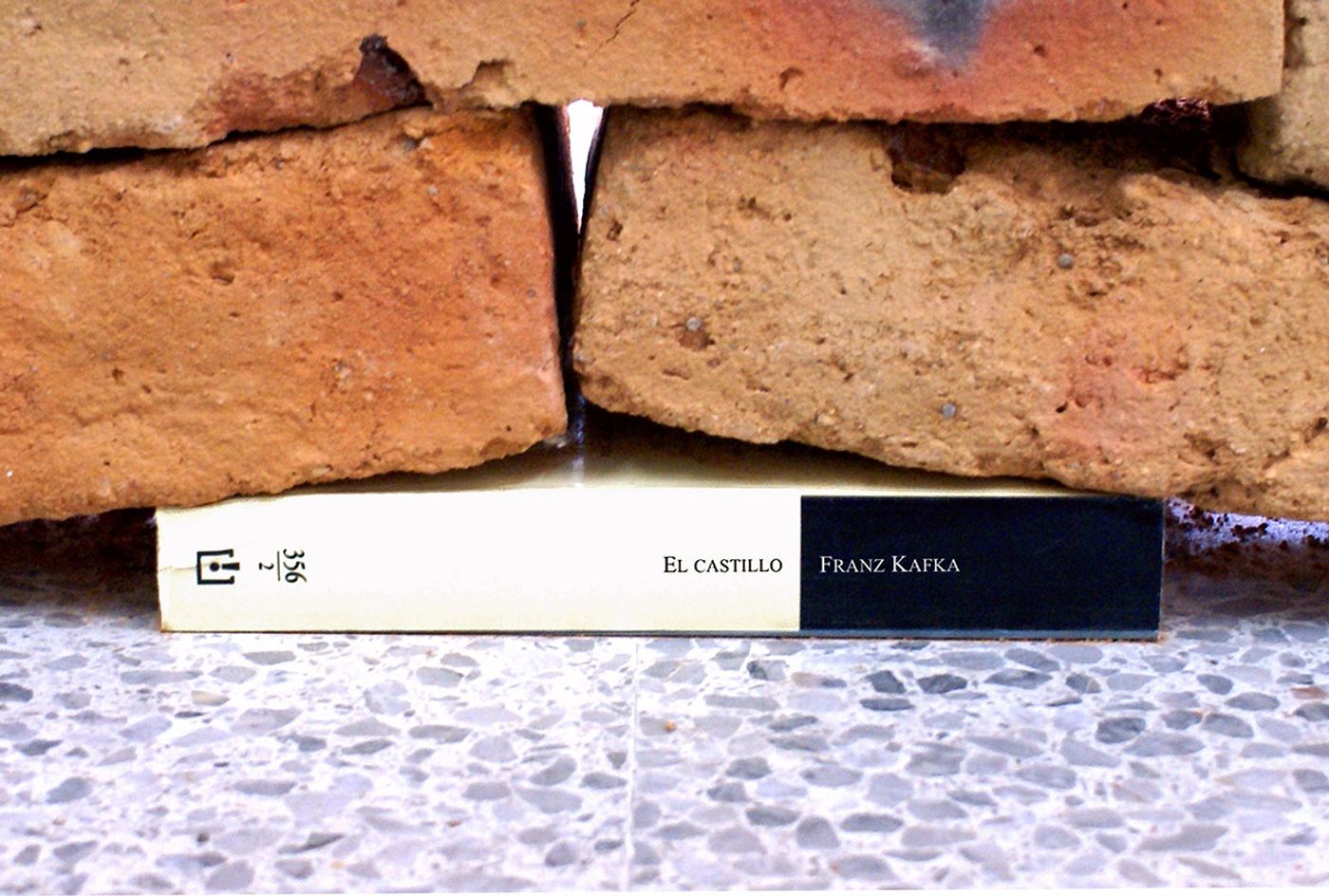

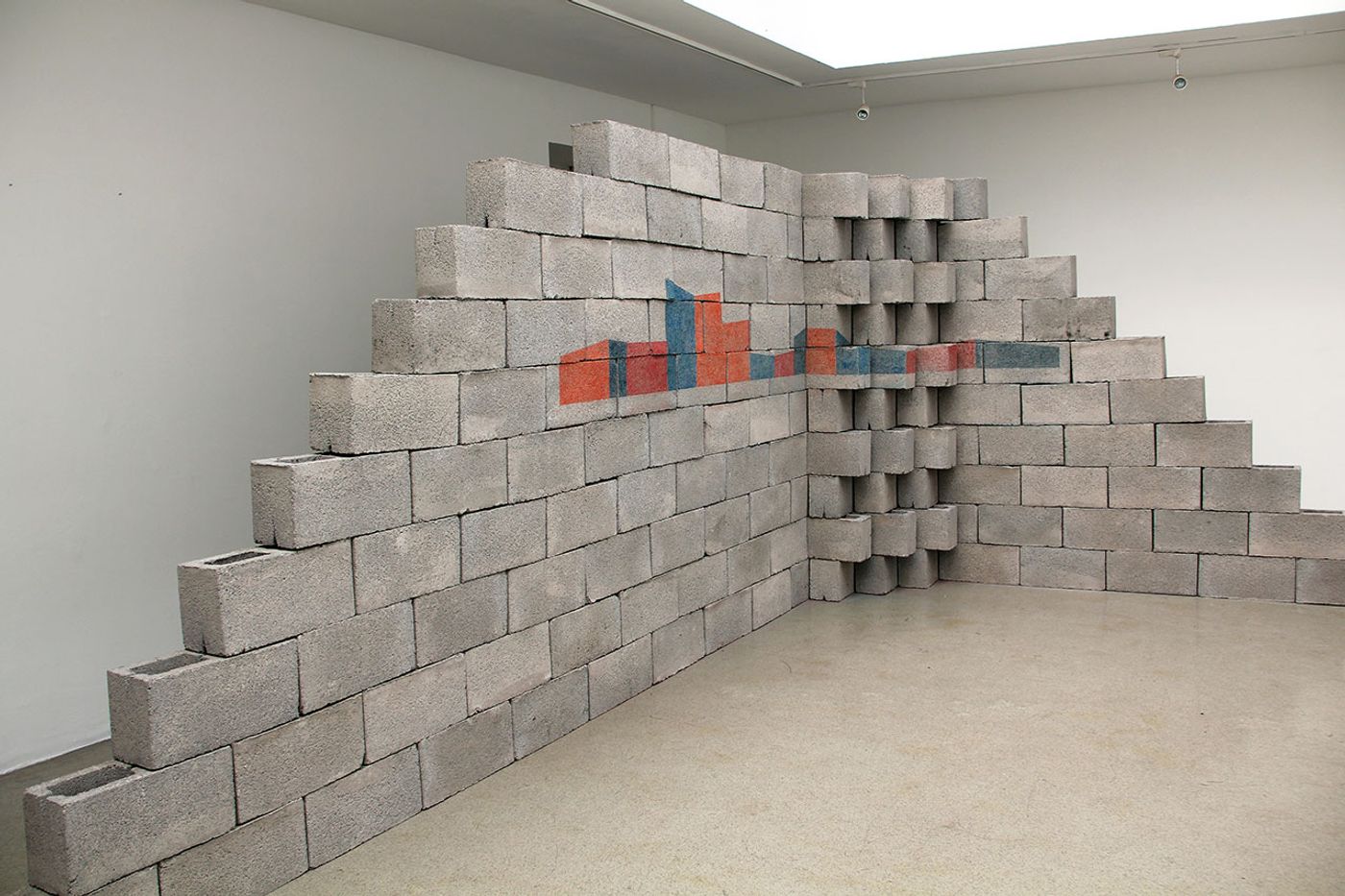

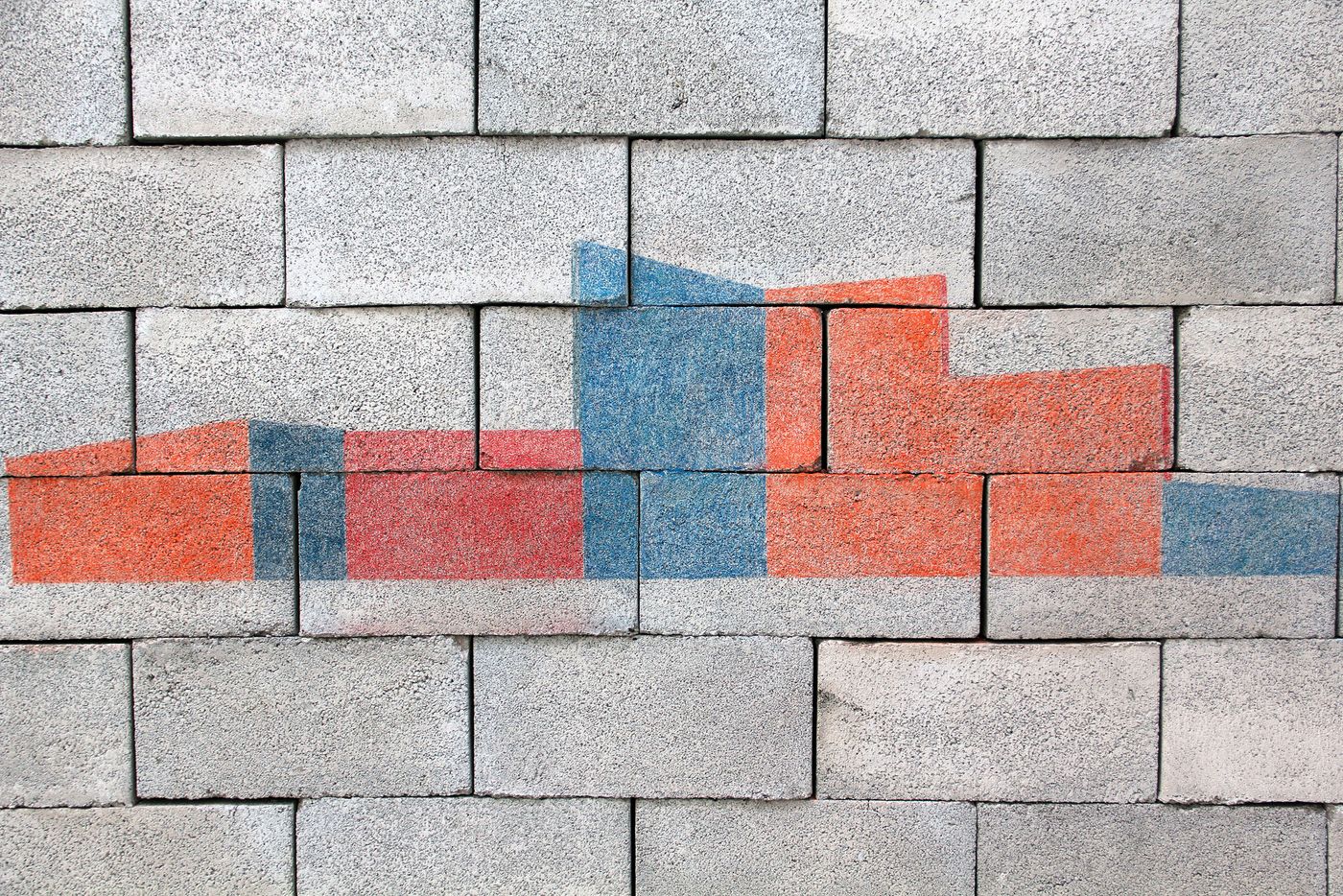

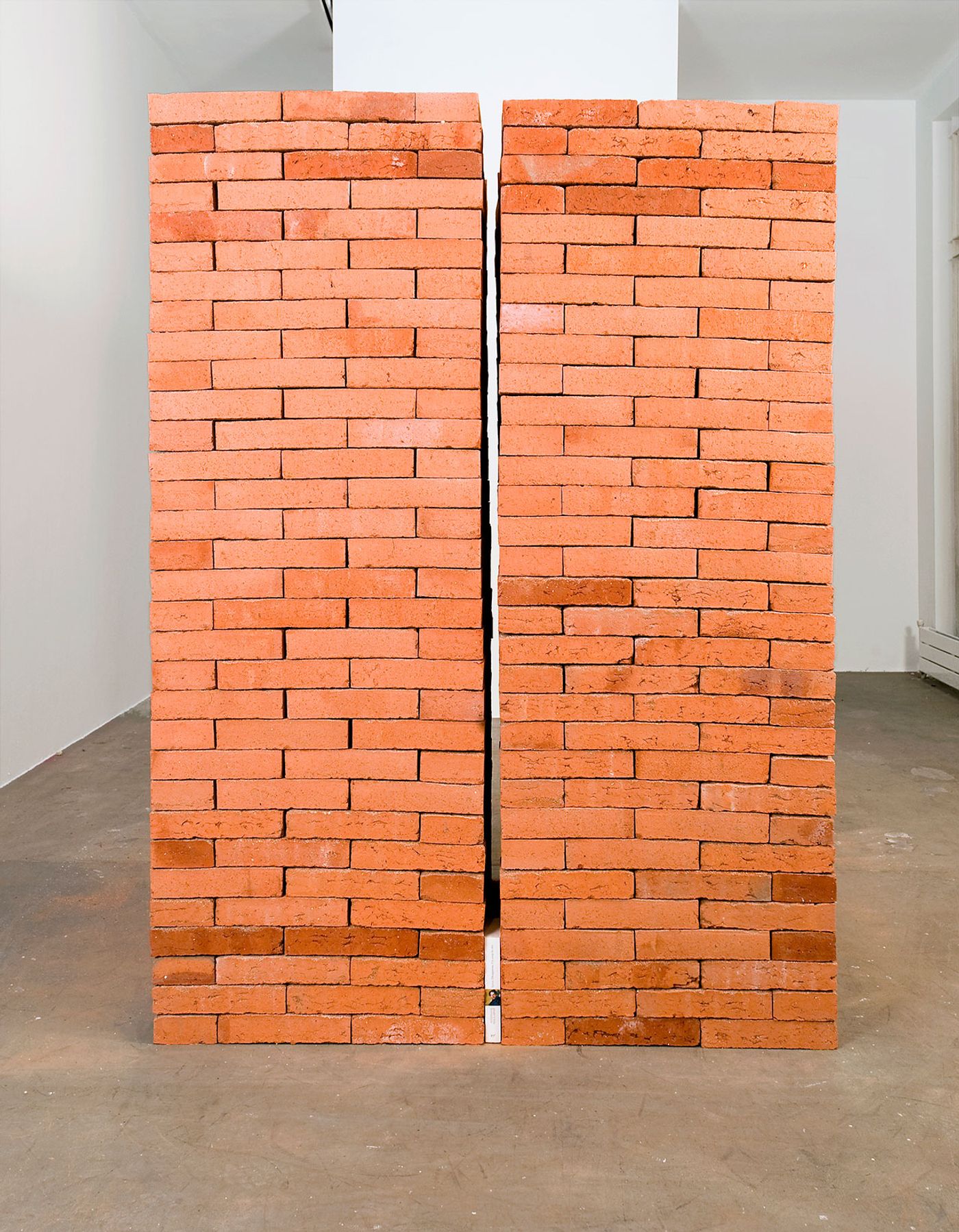

The Castle2007Bricks, edition of Franz Kafka’s 'The Castle' 2300 x 1750 x 400 cmPhoto © Jorge Méndez Blake.

With an architectural background and a life-long of love of books—he was an editor at his university’s literature magazine— it’s no wonder that the fusion of architecture and literature, the “two strongest manifestations of culture” as Méndez Blake says, is such a major preoccupation for him. An exemplary case is “Chapter VI - The Castle” (2007), a 22m long brick wall constructed by stacking bricks one on top of the another without mortar, in the middle of which, crushed underneath, is an edition of Franz Kafka’s The Castle. The book’s theme, the impossibility of its central character ever reaching the eponymous Castle, is thus re-imagined as the impossibility of ever physically reaching the book while the same time, this physical metaphor of the book’s plot spatially unfolds the book’s narration.

The Castle2007Bricks, edition of Franz Kafka’s 'The Castle' (detail)2300 x 1750 x 400 cmPhoto © Jorge Méndez Blake.

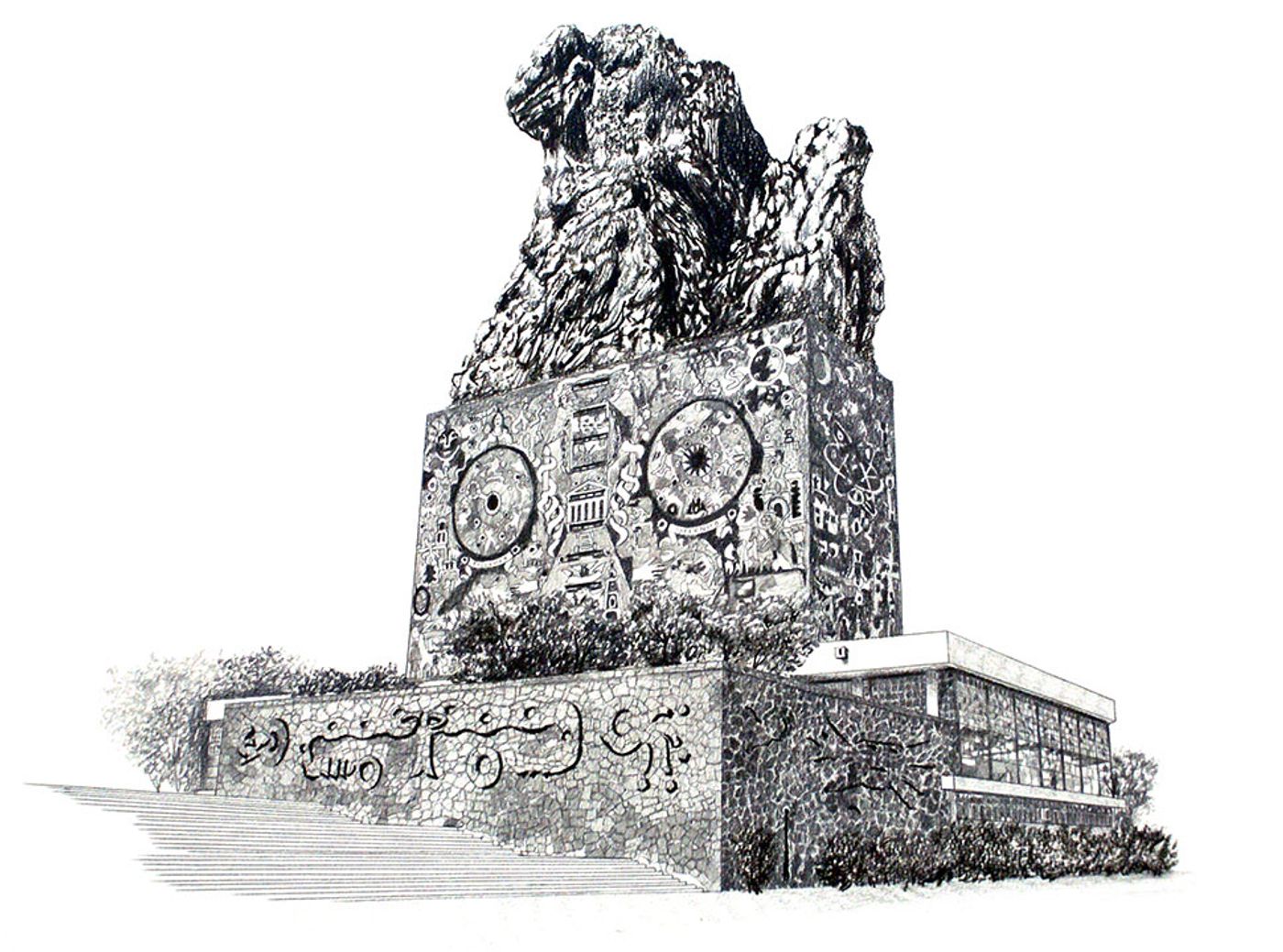

Ceboruco Volcano. Structure II2012 Concrete blocks and coloured pencilDimensions variablePhoto © Jorge Méndez Blake.

Ceboruco Volcano. Structure II (detail)2012 Concrete blocks and coloured pencilDimensions variablePhoto © Jorge Méndez Blake.

Taking the concept of literary architecture one step further, “Chapter XXIV – Monuments (2012)” pays homage to some of the greatest writers from the past two centuries by creating physical edifices inspired by both their lives and their texts. The Camus Monument, a copy of Camus’ L’étranger under a tower of bricks reflected by a mirrored table-top, is a sculptural metaphor of the book’s narrator who can see nothing beyond his own self and who is thus crushed by society, whereas the Emily Dickinson Monument, an all-white replica of her house in Amherst, Pennsylvania with a missing façade revealing a hollowed-out, red interior, alludes to the poet’s extremely introverted life. The minimalist appearance of these works belies a complex conceptual process by which the artists distils the authors’ ideas and idiosyncrasies into his art.

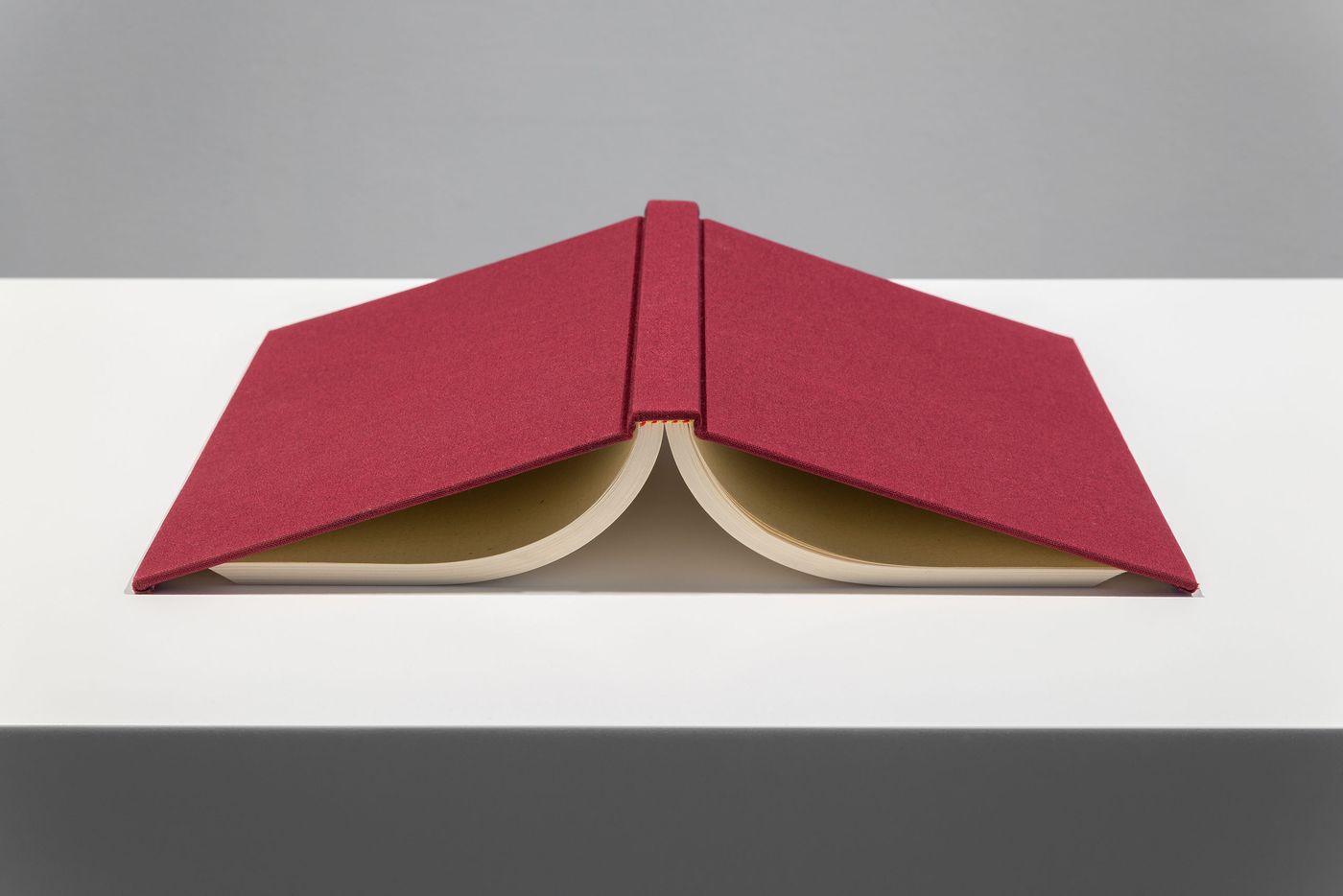

Vita activa / Vita contemplativa (Como la lluvia) (detail)2015Book, plinth109 x 56 x 38 cmPhoto © Jorge Méndez Blake.

Left:Chamber Music (James Joyce). White2014Aluminum tubes,electrostatic painting.36 piecesVariable heights: 80.8 – 294.7 cm x 1.50 – 2.54 cmRight:Chamber Music (James Joyce). Black 2014Aluminum tubes,electrostatic paint.36 piecesVariable heights: 80.8 – 294.7 cm x 1.50 – 2.54 cmPhoto © Jorge Méndez Blake.

The Mountain that Took the Place of a Poem ( For Emily)2016Metal, marble150 x 250 x 250 cmPhoto © Jorge Méndez Blake.

The visualisation of poetry is another area of great interest for Méndez Blake who has tackled it from several angles. In “Chapter XXV – Poems” (2013) he has created monochromatic wall paintings based on the works of Hart Crane, Paul Valéry, and José Goristiza by translating their poems’ lines into solid jagged strips, literally blocking out their meaning and thus imbuing them with a new, pictorial dimension. In a more sculptural approach, “Chamber Music (James Joyce)” from “Chapter XXXII - Measuring Poetry” (2014) consists of 36 iron tubes of varying lengths leaning against the gallery wall; representing the 36 poems in Joyce’s collection, each tube has the length of a poem if its words were placed next to each other in a line. For his latest body or work, “Chapter XXXV – Ventana Poniente” (2016), the artist has collected all the dashes in all six volumes of Dickinson’s poems and transferred them on 10-foot tall linen canvases using cut-outs and acrylic paint. The dashes, signifying a pause between the lines, a moment of reflection or uncertainty, visualised in such a grand manner convey the poet’s emotional turmoil that lay behind the poems’ creation.

From an Unfinished Work (The Journal of Julius Rodman) (detail)2014Aluminum, lacquer, silk screen print85 pieces of 15 x 15 x 15 cm; 10 x 10 x 10 cm; 5 x 5 x 5 cmFinal dimensions variablePhoto © Jorge Méndez Blake.

Untitled2015Wood, oil lamp45 x 20 x 20 cmPhoto © Jorge Méndez Blake.

Du fond d’un naufrage 2011Bricks, edition of 'Poésies et autres textes' by Stéphane Mallarmé161 x 120 x 106 cmPhoto © Jorge Méndez Blake.

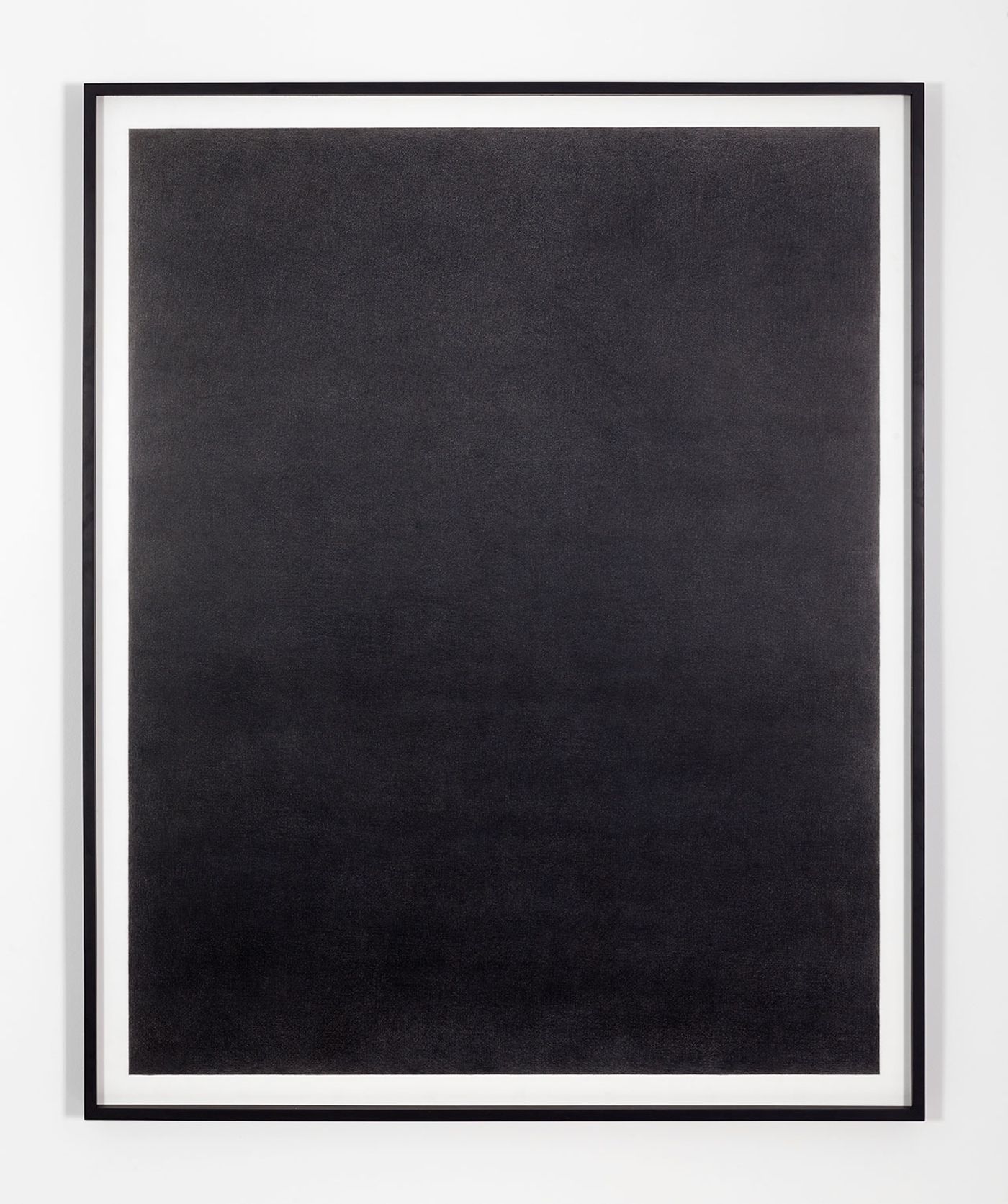

Empty Bookshelf II2011Coloured pencil on paper150 x 120 cmPhoto © Jorge Méndez Blake.

It Was a Pleasure to Burn X2015Coloured pencil on paper150 x 120 cmPhoto © Jorge Méndez Blake.

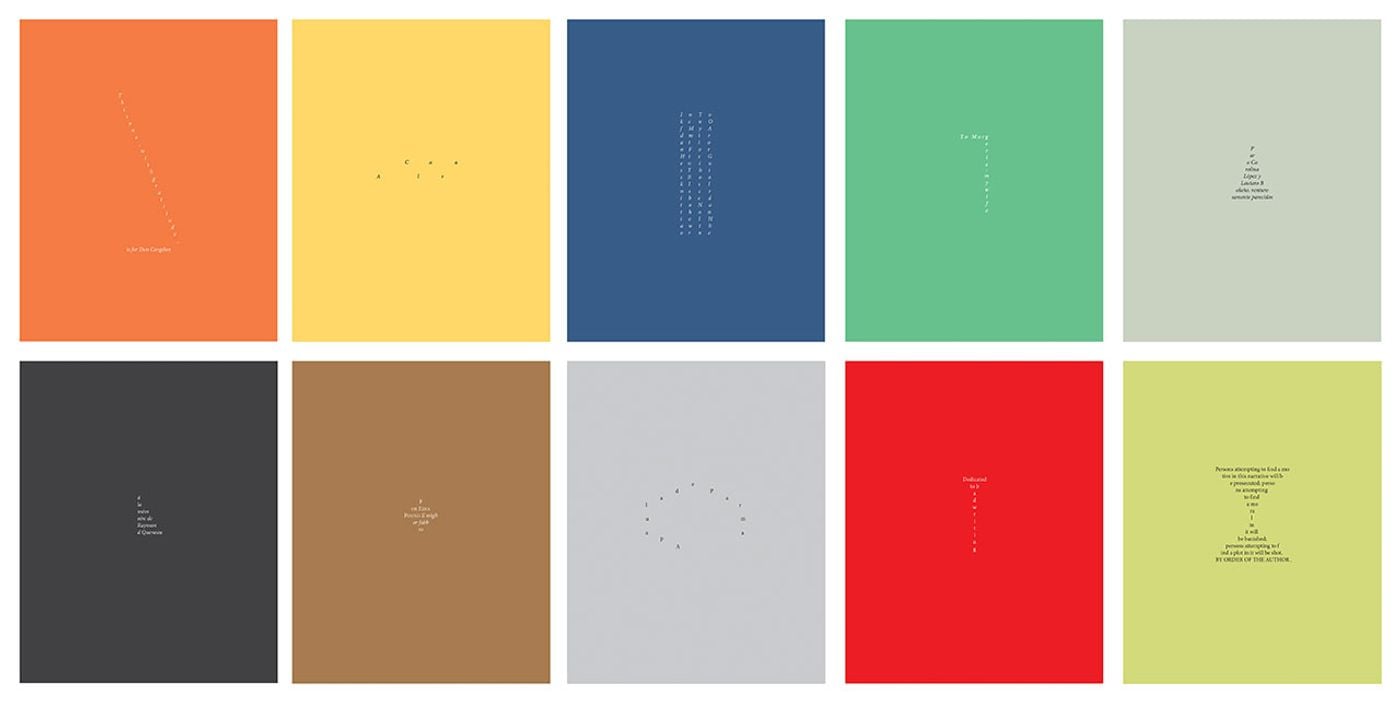

Dedicatorias2015Fine art printPolyptych of 8 pieces of 100 x 80 eachPhoto © Jorge Méndez Blake.

Left:Projects for Romeo and Juliet Library2009Right:Study for a Library About Love 2009Paint on wallDimensions variablePhoto © Jorge Méndez Blake.

Left:Werther Bookshelf2009Stainless steel, books14 books200 x 145 x 30 cmRight:El amor en los tiempos del cólera2009Stainless steel, books31 books200 x 145 x 30 cmPhoto © Jorge Méndez Blake.

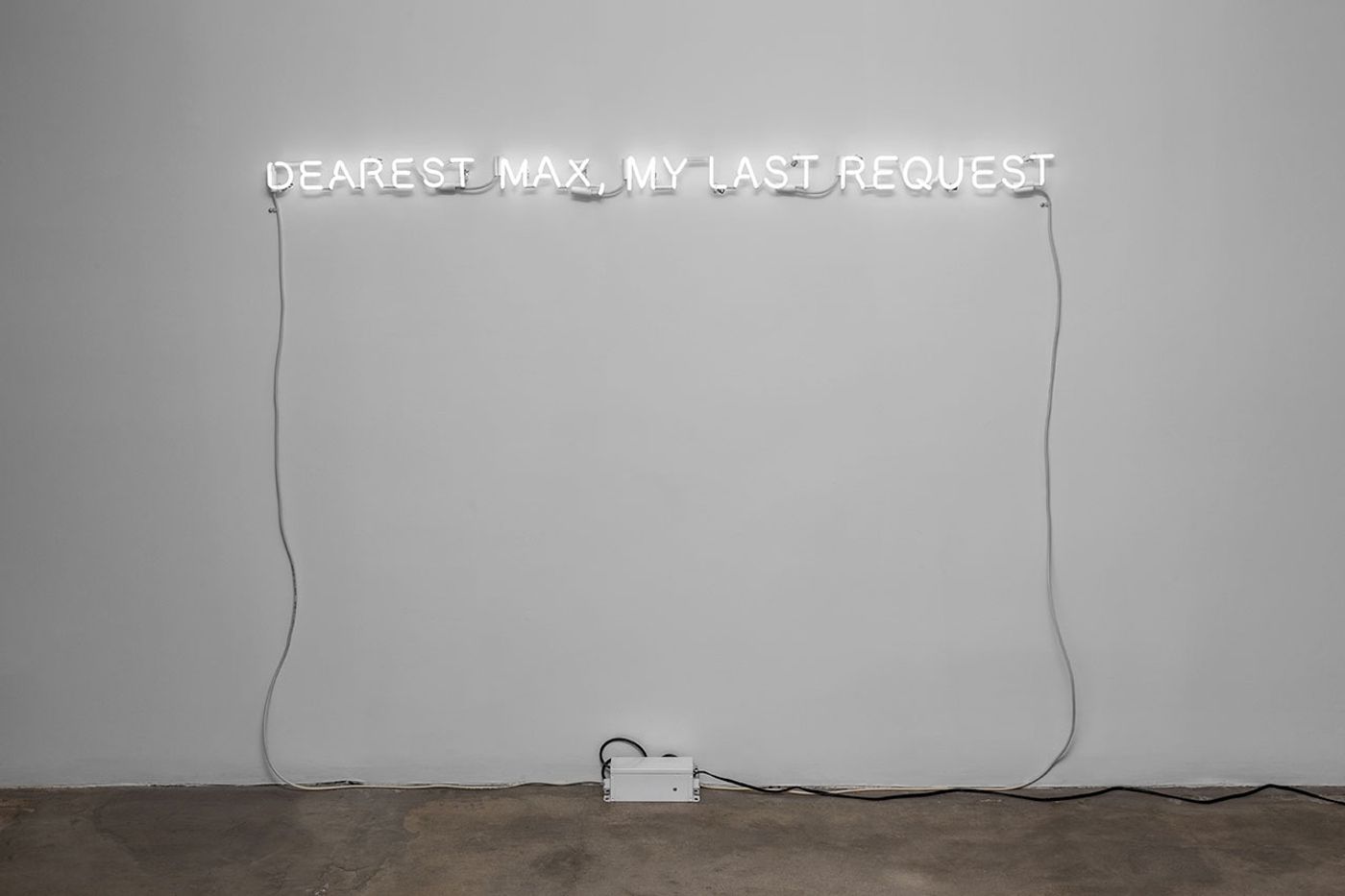

Dearest Max, My Last Request2015Neon8 x 185.5 cmPhoto © Jorge Méndez Blake.