How Your Neighbours See You: 'Out my Window' Photo Series by Gail Albert Halaban

Words by Eleni Papaioannou

Location

How Your Neighbours See You: 'Out my Window' Photo Series by Gail Albert Halaban

Words by Eleni Papaioannou

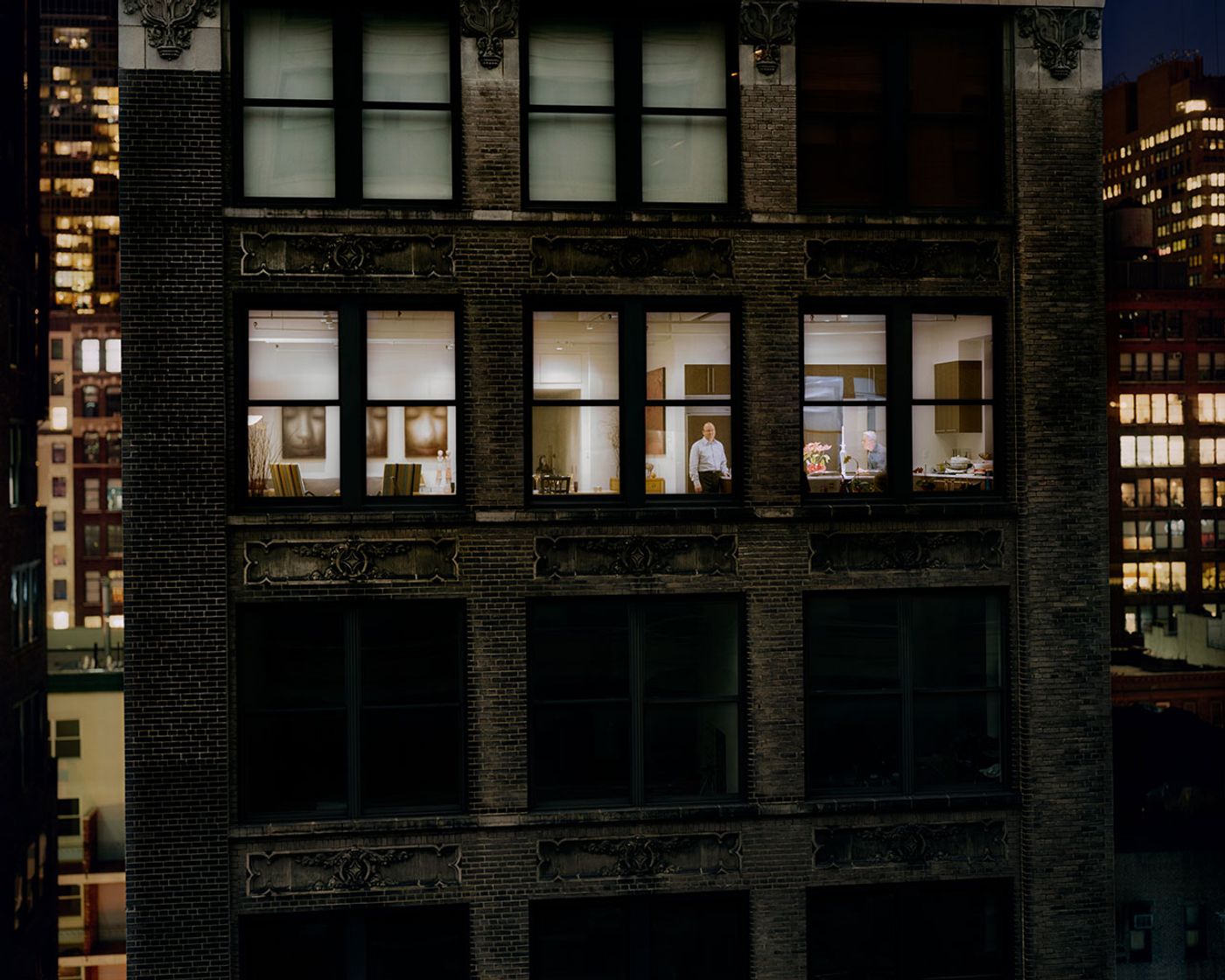

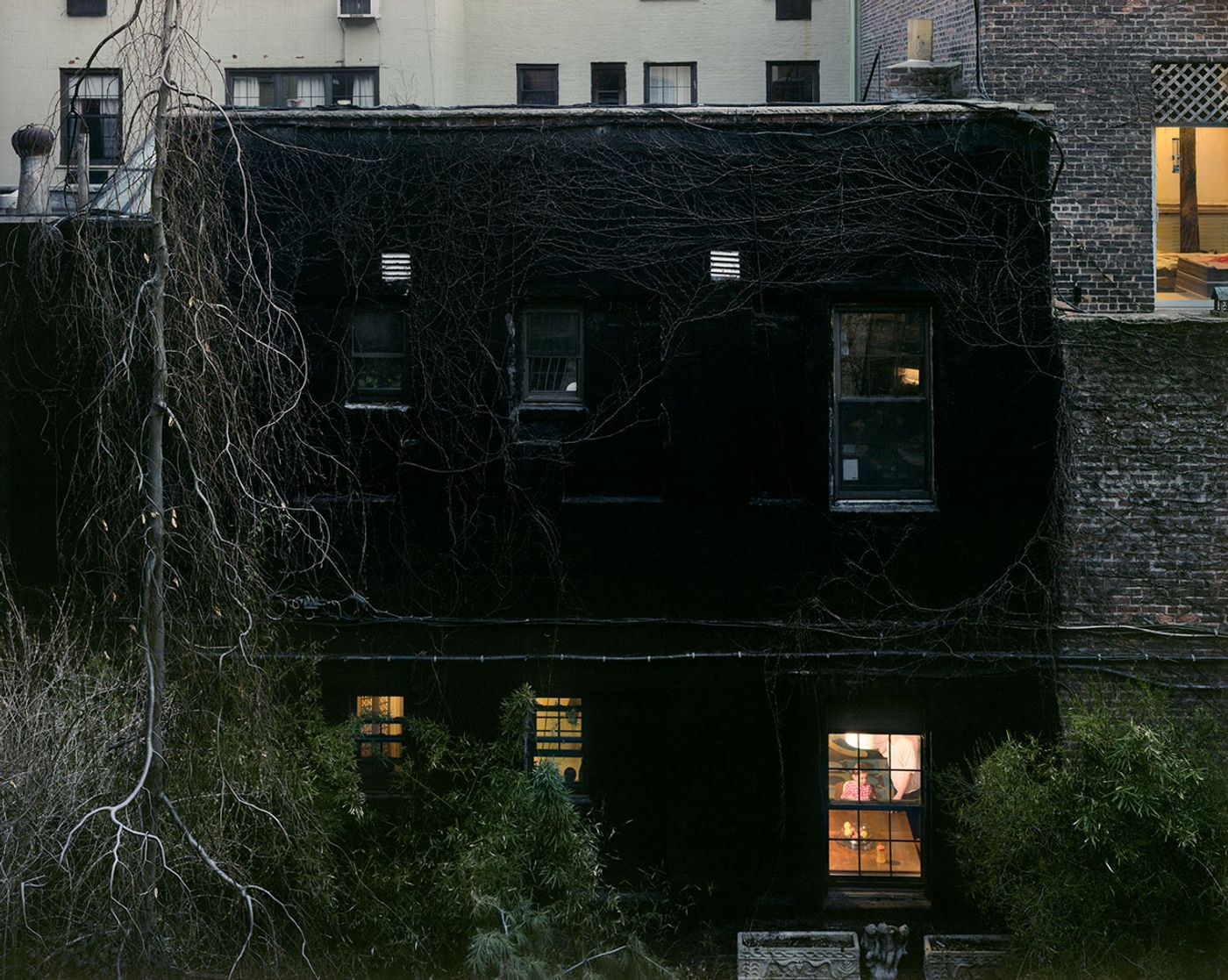

Living in the city, with our apartments stacked so close to one another, our lives are intertwined without us ever truly knowing each other. We become familiar with our next-door noises, the comforting sounds of a table being set or a bath being prepared, but the real stories of the people living only a few breaths away we can only guess, by sometimes catching a glimpse, or even a long stare of detached familiarity, through a lit, open window. It is these slices of everyday life that provide perfect scenarios for Gail Albert-Halaban, a New York based photographer, to examine in her project “Out My Window”.

Out my window, New York City. Photo © Gail Albert Halaban.

Out my window, New York City. Photo © Gail Albert Halaban.

Out my window, New York City. Photo © Gail Albert Halaban.

Out my window, New York City. Photo © Gail Albert Halaban.

Vis–à–vis, Paris. 26 September 2013, Quai Anatole. Photo © Gail Albert Halaban.

It all began a few years back, when the photographer’s newborn baby would wake her up at random hours during the night, and the only narrative she had to keep her company through her window was of a 24–hour flower shop across the street, that eventually became her first subject: “I was inspired by the artist Ruth Orkin who photographed out her window. The photos I took were not all that great, but they became the first in the series”, she recalls. As soon as the shop changed hands –and hours, Halaban knew she couldn’t stop. She wanted to see the whole city: “The best way to see it is from above, and a great way to do that is from people’s apartments”.

Out my window, New York City. Photo © Gail Albert Halaban.

Out my window, New York City. Photo © Gail Albert Halaban.

Out my window, New York City. Photo © Gail Albert Halaban.

Out my window, New York City. Photo © Gail Albert Halaban.

She started by talking to people she knew, asking them to show her who they looked at, through their windows. In a daring move that manifests the power of art to change, not only the way we see but also the way we react to others, she brought the voyeurs and their subjects together, creating a cooperation that would lead to staged, yet simple everyday scenes she depicted with her camera: “I love to connect people who are part of each other's lives but have never met before” she says. When the resulting images became a book (by powerHouse Books), Le Monde newspaper commissioned her to shoot a similar series in Paris. Through Facebook messages, letters, sometimes even notes left to doormen, Halaban first met with her subjects, and, usually over some wine, they ended up happily engaging in her project. From then on the series took on a life of its own, and now takes Halaban around the world: “I just got back from Istanbul and I am heading to Buenos Aires”, she tells us. To her, “the life of a city is a marriage between the people and the architecture. Every city is different. Culture is a huge part of the work, as is the architecture. No two places have been alike”.

Out my window, New York City. Photo © Gail Albert Halaban.

Out my window, New York City. Photo © Gail Albert Halaban.

Out my window, New York City. Photo © Gail Albert Halaban.

Out my window, New York City. Photo © Gail Albert Halaban.

However different the landscapes, her photographs always capture, within them, the portraits of strangers that seem to be caught in private moments. Exploring the tension between public and private life, the artist examines what is seen by all, together with what is hidden. Her “voyeuristic” architectural images have thus been frequently compared to Edward Hopper’s art. Halaban, as so many artists usually do, admits to “often looking at life in frames”, so the discussion inevitably stumbles upon Jimmy Stewart’s character in Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window, where he plays a New York photographer spying on his neighbors from his window, using his camera. But to Halaban, photography is not voyeurism: “Quite the opposite, photography has been a chance for me to get to know people and connect with them on a face to face basis. I always meet the people I photograph before I bring a camera”, she says. Meeting with strangers and finally bringing anonymous neighbors into each other’s lives seems to serve as a remedy to the symptoms of loneliness and detachment Halaban actually focuses on in her series. The resulting effect literally leaps out of her frames, reaching her viewers, as the photographer believes: “If people really look at the pictures they can make up stories and sort of meditate on them, thus becoming part of the project.”

Out my window, New York City. Photo © Gail Albert Halaban.

Out my window, New York City. Photo © Gail Albert Halaban.

Out my window, New York City. Photo © Gail Albert Halaban.

Out my window, New York City. Photo © Gail Albert Halaban.

Out my window, New York City. Photo © Gail Albert Halaban.

Out my window, New York City. Photo © Gail Albert Halaban.

Out my window, New York City. Photo © Gail Albert Halaban.

Vis–à–vis, Paris. 18 May 2013 Rue du Faubourg du Temple. Photo © Gail Albert Halaban.

Vis–à–vis, Paris. 18 May 2013 rue du Faubourg du Temple. Photo © Gail Albert Halaban.

Vis–à–vis, Paris. 17 May 2013, rue du Faubourg Saint-Denis. Photo © Gail Albert Halaban.

Vis–à–vis, Paris. 31 October 2013, Rue Du Guesclin. Photo © Gail Albert Halaban.

Vis–à–vis, Paris. 19 May 2013, bis rue de Douai. Photo © Gail Albert Halaban.