Immerse Yourself in Art, Life and Politics of Interwar Italy in Fondazione Prada’s POST ZANG TUMB TUUUM

Words by Eric David

Location

Milan, Italy

Immerse Yourself in Art, Life and Politics of Interwar Italy in Fondazione Prada’s POST ZANG TUMB TUUUM

Words by Eric David

Milan, Italy

Milan, Italy

Location

Hosted in Fondazione Prada’s Milan venue, “Post Zang Tumb Tuuum. Art Life Politics: Italia 1918–1943” is a sprawling retrospective of Italian art and culture during the interwar years that aims to immerse the visitor in an era when artistic liberalism co-existed with creeping fascism, avant-garde ideas clashed with revivalist attempts, and utopian dreams encountered an ominous reality.

The exhibition not only showcases a wide selection of works of art that represent the artistic movements, themes and major voices of the era, but more importantly reconstructs the historical and cultural context in which they were created and exhibited, in some cases literally. Conceived by New York studio 2x4 in collaboration with the exhibition’s curator Germano Celant, the show has been set up in and around twenty partial reconstructions of public and private exhibition rooms. Along with a trove of meticulously selected documentation that includes more than 500 paintings, sculptures, drawings, photographs, posters, pieces of furniture, and architectural plans and models by over 100 authors, the exhibition re-contextualizes the art and culture of interwar Italy in the most vivid and comprehensive fashion.

After the First World War, when promises of territorial expansion were dashed, Italy found itself not only burdened with inexorable debt but also demoralized. This environment, coupled with the instability of a recently adopted democratic system and widespread civil unrest, allowed Mussolini to take over the country with his populist and nationalistic agenda in 1922. Although the fascist regime controlled and censored most cultural production like media and film, art and architecture were relatively spared due to the regime’s conflicting platform that promoted both the return to the classical order of Italy’s illustrious past and the establishment of a modern state of technological innovation.

Renato Guttuso, Ritratto di Mario Alicata, 1940 Oil on canvas, 55 x 45 cm. Iannaccone collection © Renato Guttuso by SIAE 2018.

Piero Portaluppi, Italian Pavilion at the Barcelona International Exposition, 1928-1929. Photo: Fondazione Piero Portaluppi, Milano © Fondazione Piero Portaluppi, Milano.

This socio-political context gave rise to a rich variety of movements such as Futurism, the expressionistic Scuola Romana, the traditionalist Ritorno all’ordine (Return to order) that spawned the “Novecento Italiano” exhibitions, and the re-evolutionary Les Italiens de Paris. The most famous of the latter is the co-founder of Pittura Metafisica (Metaphysical Αrt), Giorgio De Chirico, whose haunting and evocative paintings combine a neo-baroque aesthetic with a surrealist sensibility and whose “Hall of Gladiators”, designed and painted in 1929 as the reception room of the Parisian home of Léonce Rosenberg, at the time a prominent art dealer and gallery owner, has been reconstructed for the exhibition.

De Chirico’s paintings had a strong influence on the Surrealist movement and drew international acclaim as attested by two New York shows documented in the exhibition, MoMA’s “Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism" in 1936-1937 and the 1940’s “Giorgio De Chirico, Exhibition of Early Paintings” at the Pierre Matisse Gallery. They are also a testament to the promotion of Italian art abroad seen in Pittura Metafisica's co-founder Carlo Carrà’s solo show at Umelecka Beseda in Prague in 1932 and Giorgio Morandi’s participation at “Das junge Italien” at Berlin’s Nationalgalerie in 1921.

Installation view of “Giorgio De Chirico, Exhibition of Early Paintings”, Pierre Matisse Gallery, New York, 1940. Among the exhibited works: La nostalgie de l'ingénieur (1916) - For the work © Giorgio De Chirico by SIAE 2018 Pierre Matisse Gallery New York, N.Y. archives, 1903-1990, Box 100The Morgan Library & Museum. MA 5020. Gift of the Pierre Matisse Foundation, 1997. 3. 205567v_0534 Black-and-white editorial.

Giorgio De Chirico, Le caserme dei marinai, 1914, oil on canvas, 81,3 x 64,8 cm. Courtesy Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach. Photo: Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach, Florida, Bequest of R.H. Norton, 53.30 © Giorgio De Chirico by SIAE 2018.

Giorgio De Chirico, La nostalgie de l’ingénieur, 1916, oil on canvas, 33,7 x 24 cm. Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk © Giorgio De Chirico by SIAE 2018.

Rendered photographic image for “Post Zang Tumb Tuuum” (Fondazione Prada, Milan, 2018). Installation view of "Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism" at MoMA, New York, 1936-1937. Among the exhibited works, Le caserme dei marinai (1914) by Giorgio De Chirico - For the work © Giorgio De Chirico by SIAE 2018 © 2017. Digital Image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York / Scala, Firenze Photo Soichi Sunami.

As expected, the exhibition dedicates considerable resources and space to examining the great public exhibitions such as the Venice Biennale, the most impressive of which is the reconstruction of the room devoted to sculptor Adolfo Wildt in 1922, and the Rome Quadriennale, which was founded in 1931 in order to boost the national art system and which is showcased here through the reconstruction of the room devoted to painter Gino Severini at the 1935 edition.

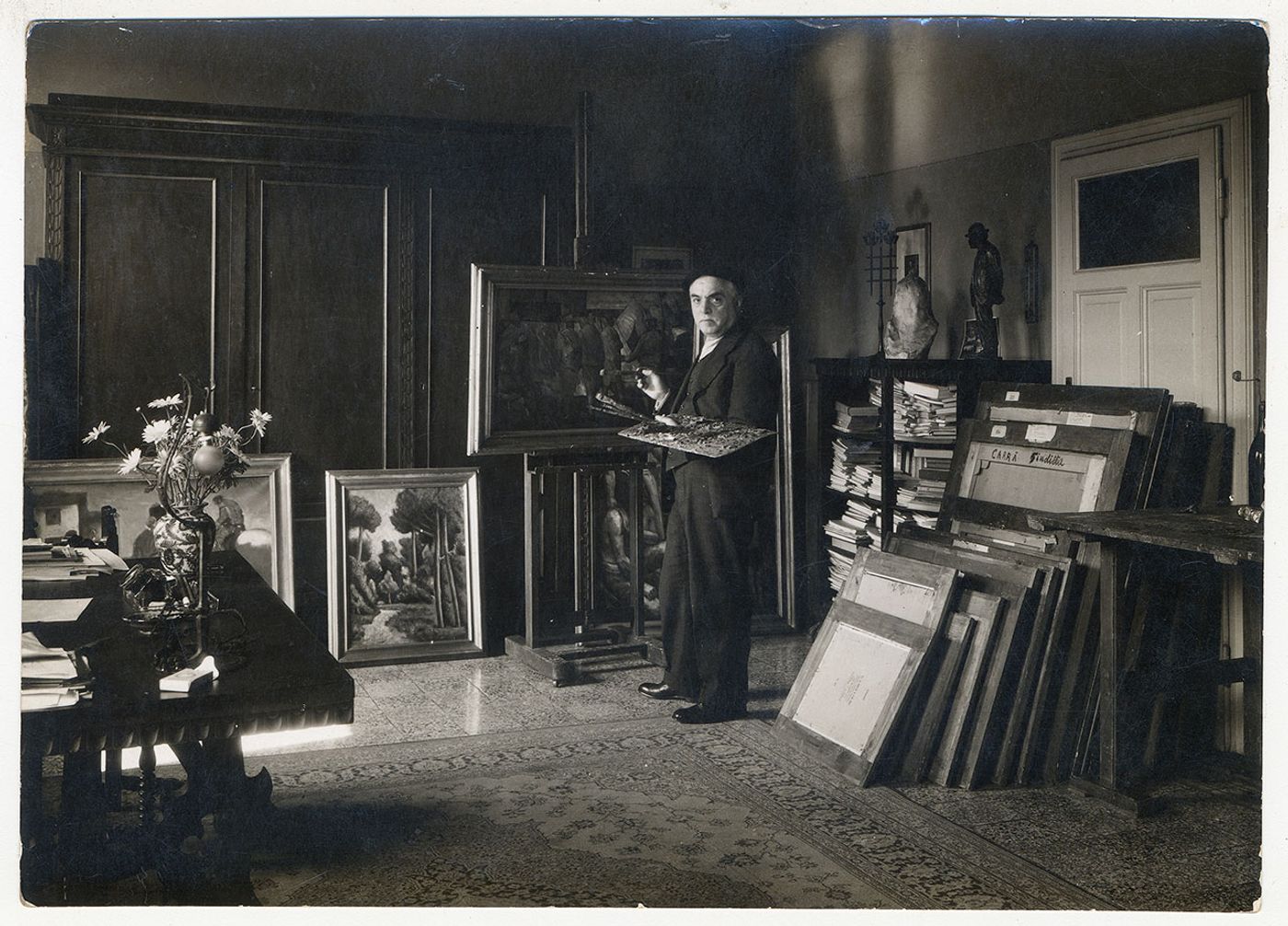

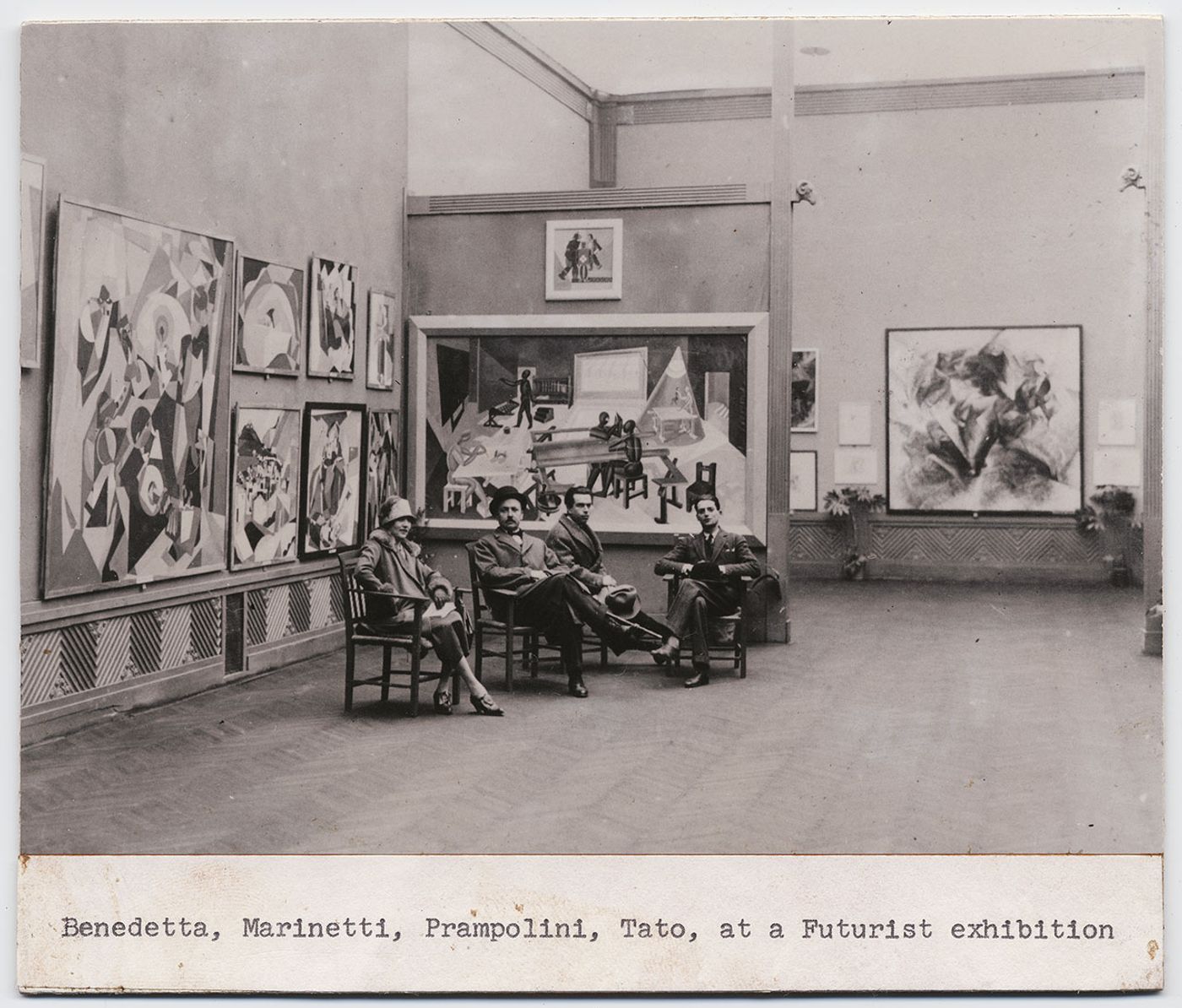

With its emphasis on speed and technology, the glorification of war and the rejection of the past, Futurism found fertile ground to flourish during the rise of Fascism in Italy and the show allows the visitor to contextualize many works by highlighting the exhibition spaces that hosted them. One of those is Umberto Boccioni’s "Dinamismo di un footballer" (1913) which visitors can admire alongside photographs of the Futurist exhibition at the Biennale di Roma in 1925 where it was first displayed as well as photographic renderings from 1934 that depict the home of Futurism founder Filippo Tommaso Marinetti.

Rendered photographic image for “Post Zang Tumb Tuuum” (Fondazione Prada, Milan, 2018). Filippo Tommaso Marinetti in his home (from "Wiener Illustrierte Zeitung" and "Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung", 1934) in the background "Dinamismo di un footballer" by Umberto Boccioni, 1913. Ullstein Bild / Archivi Alinari © 2017. Digital Image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York / Scala, Firenze.

Giacomo Balla, Canaringatti - Gatti futuristi , 1923-1924, oil on canvas, 66 x 194 cm. Courtesy Galleria d'Arte Maggiore GAM, Bologna/Milano © Giacomo Balla by SIAE 2018.

Installation view of III Biennale di Roma 1925 – Futurist group show curated by F. T. Marinetti. Wall A: works by Giacomo Balla, Fortunato Depero and Gerardo Dottori Among the exhibited works, Canaringatti - Gatti futuristi (1923-1924) by Giacomo Balla - For the work © Giacomo Balla by SIAE 2018. Image published in the magazine EMPORIUM. Archive E. Gigli, Roma.

Other documented shows include the Esposizione Internazionale di Belle Arti della Società Amatori e Cultori di Belle Arti di Roma in 1928, whose room VII hosted Giacomo Balla’s “Quadro fascista”, a.k.a. "Le mani del popolo italiano" (1925), and the Italian Futurist exhibition at the Russian Pavilion at the XV Biennale di Venezia in 1926, where Fortunato Depero’s “La rissa” (1926) was displayed.

Although Futurism was seen positively by the fascist regime, it often clashed with its preference for the classical forms of Imperial Rome. Ritorno all’ordine (Return to order) on the other hand, was a movement much more aligned with fascist ideals and the exhibition take great pains to reconstruct the first and second “Novecento Italiano” exhibitions, orchestrated by Mussolini’s mistress Margherita Sarfatti at the Permanente in Milan through the use of archive materials such as catalogues, photographs, and historical documents.

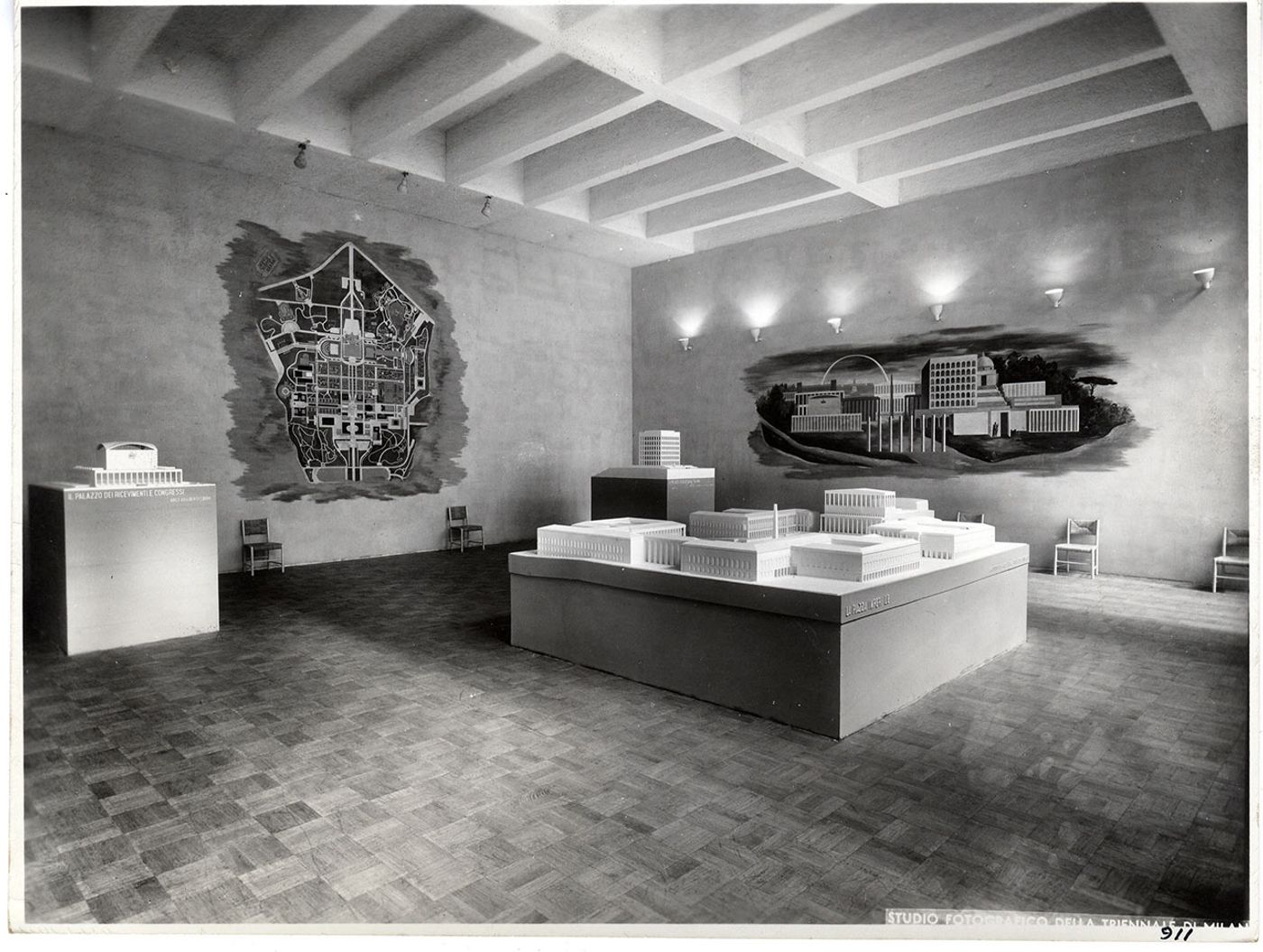

Salone delle Cerimonie, V Triennale di Milano, 1933. Works by Sironi, Severini, De Chirico, Campigli and Funi. Photographic archive © La Triennale di Milano. Photo: Crimella.

Felice Casorati, Ritratto di Renato Gualino, 1923 - 1924, oil on plywood panel 97x74,5 cm. Courtesy Istituto Matteucci, Viareggio © Felice Casorati by SIAE 2018.

Alberto Savinio, Les Atlantes, 1931, oil on canvas 65 x 80 cm. Private collection. Courtesy ED Gallery, Piacenza. Photo Sergio Amici © Alberto Savinio by SIAE 2018.

“Mostra nazionale dello sport” (National exhibition of sport), Triennale di Milano, 1935. Set-up by studio BBPR. Photographic Archive © La Triennale di Milano. Photo: Crimella.

The state’s controlling power over the country’s cultural production is also evident through the large official expositions that it organized like the monumental Mostra della Rivoluzione Fascista (1932), the Esposizione dell’Aeronautica Italiana (1934), and the Mostra Nazionale dello Sport (1935). The former, staged at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni and subsequently at the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome for the tenth anniversary of the regime, became a powerful propaganda tool for the regime and its documentation takes centre stage in the venue’s Deposito rooms. At the same time, autonomous voices, both conciliatory and dissenting, vocal and quiet, can be observed through thematic exhibits of important politicians, intellectuals, writers and thinkers that punctuate the show.

Fittingly, the exhibition title is a reference to Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s seminal work of modernist art, Zang Tumb Tuuum, a poem about the Battle of Adrianople that uses phonetic, spatial and typographical elements to enhance the verbal meaning of the words. Published as an artist's book in Milan just before WWI, it went on to influence a number of artists including several featured in the exhibition like Balla, Carrà and Boccioni, and ushered in the modernist ethos of the interwar period as well as herald the subsequent establishment of fascism in Italy—Tommaso was the author of both the Futurist Manifesto in 1909 and, a decade later, the Fascist Manifesto. With its rhythmic yet menacing titular verse, which is also the book's closing stanza, it couldn’t be a more appropriate slogan for such a paradoxical era of Italian history that Fondazione Prada has so masterfully documented.

Giacomo Balla, Quadro fascista (also known as Le mani del popolo italiano), 1925 ca. three panels enamel on canvas, cm 173 x 113,5 (each). Roma, già Casa Balla © Giacomo Balla by SIAE 2018.

Rendered photographic image for “Post Zang Tumb Tuuum” (Fondazione Prada, Milan, 2018). Photo of the Esposizione Internazionale di Belle Arti della Società Amatori e Cultori di Belle Arti in Roma, room VII Amatori e Cultori, 1928. Among the exhibited works: Quadro fascista (also known as Le mani del popolo italiano) (1925) by Giacomo Balla - For the work © Giacomo Balla by SIAE 2018.

Carlo Levi, L'arciprete di Aliano, 1936. oil on canvas, 61 x 50 cm. Museum of Medieval and Modern Art of Palazzo Lanfranchi, Matera. On concession of the Ministry of Cultural Heritage, Activities and Tourism. Photo archive of the Polo Museale of Basilicata © Carlo Levi by SIAE 2018.

Brochure of Galleria della Cometa on the occasion of the exhibition by Carlo Levi in1938 - For the work © Carlo Levi by SIAE 2018. Sovrintendenza Capitolina ai Beni culturali – Direzione Musei, Ville e Parchi Storici – Musei di Villa

Torlonia – Biblioteca e Archivio della Scuola Romana

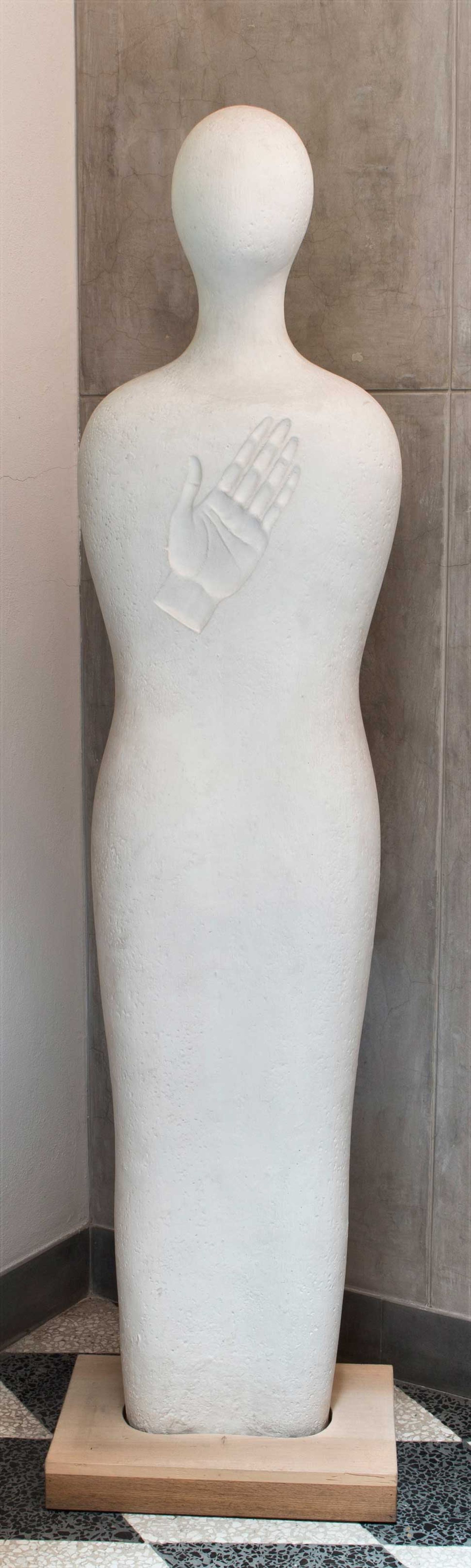

Installation view of VI Triennale di Milano, 1936. Introduction to the housing exhibition in the new Pavilion of the Sempione Park, “Coerenza” room, designed by the architecture firm BBPR. Among the exhibited works, Costante uomo (1936) by Fausto Melotti - For the work © Fausto Melotti by SIAE 2018. Photo archive © La Triennale di Milano. Photo Crimella.

Giorgio Morandi, Natura morta, 1920, oil on canvas 60,5 x 66,5 cm. Pinacoteca di Brera, Milano Copyright: MiBACT - Pinacoteca di Brera, Photo archive © Giorgio Morandi by SIAE 2018.

Rendered photographic image for “Post Zang Tumb Tuuum” (Fondazione Prada, Milan, 2018). Installation view of “Das junge Italien” at Nationalgalerie Berlin, 1921. Among the exhibited works, Natura Morta (1920) by Giorgio Morandi - For the work © Giorgio Morandi by SIAE 2018.

Pierre Roy, A Naturalist's Study, 1928. Oil on canvas, 92,1 x 65,4 cm. Tate Modern, London © Tate, London 2017 © Pierre Roy by SIAE 2018.

“Appels d’Italie” room, XVII Biennale, Venezia, 1930. Among the exhibited works, A Naturalist's Study (1928) by Pierre Roy - For the work © Pierre Roy by SIAE 2018 © La Biennale di Venezia, ASAC, Photo Library – “Attualità e Allestimenti” series – Appels d’Italie show, room 23, XVII. International Art Exhibition, 1930. Photo Giacomelli.

Adolfo Wildt, Il puro folle (Parsifal), 1930. Plaster work, 71 x 73 x 80 cm. International Gallery of Modern Art of Ca 'Pesaro, Venice. Photo Franzini C. © Stock Photo - Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia.

Installation view of I Quadriennale di Roma, 1931. Room III: view of the Accademici room including works by Adolfo Wildt. Among the exhibited works, Il puro folle (Parsifal) (1930) by Adolfo Wildt. Courtesy Fondazione La Quadriennale di Roma.