Dark Palimpsest: Graphite-laden Sculptures by Despina Flessa

Words by Kiriakos Spirou

Location

For her debut with Zoumboulakis Gallery in Athens, visual artist Despina Flessa presents a series of works that push the limits of conventional drawing materials to their extremes. Presented as part of the double exhibition “Substratum” together with works by Dimitris Efeoglou, Flessa’s sculptures and paper works are a fractured tale of remembrance and semblance, where familiar landscapes are drowned in dark noise, and memory is presented as a cumbersome process of constant accumulation.

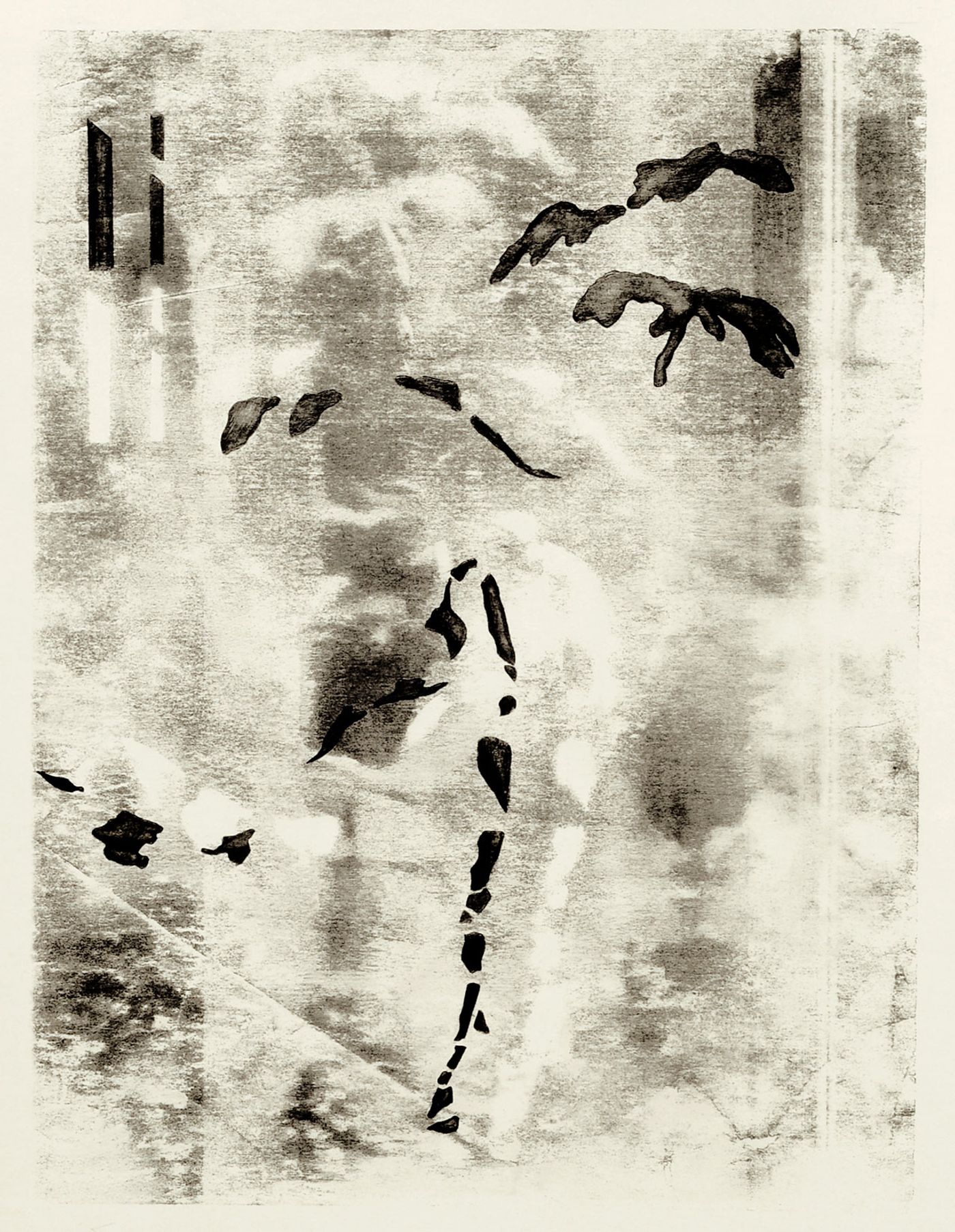

The result of a long experimental process with basic art materials, the works on display were made using large quantities of graphite, which Flessa used to cover entire sheets of paper, long stripes of wood veneer and an assemblage of mysterious clay objects. The latter combination of clay and graphite was used for the sculpture Remains (2015), a work of variable dimensions that was placed on the gallery floor like an excavation site or the remains of a fossil skeleton. “I wanted to polish the clay, to give it a metallic shine and make it look precious,” Flessa tells me as we walk around the three-meter-wide assortment of fractured blackness. “It looks like a fossil that’s just been dug up because I wanted it to remind the pictures on the wall somehow.” She points to the wall, where images of natural landscapes are placed inside plexiglass cases, one of which indeed shows an archaeological site. “It’s in the Peloponnese,” Flessa says. “They were doing electricity works and found these prehistoric remains there, so the works stopped.”

Despina Flessa, Remains, graphite print and graphite on paper, 46 x 35 cm, 2015. Photo by Costas Christou.

Despina Flessa, Excavation, graphite print, 12 x 17,5 cm, 2015. Photo by Thomas Gerasopoulos.

Despina Flessa, Remains, graphite on clay, variable dimensions, 2015. Photo by Thomas Gerasopoulos.

The little black forms of Remains look like lumps of coal in the photos, but from up close they really give the impression of polished steel. They appear heavy and, just as Flessa intended, precious. “I made these by covering them with multiple layers of water-soluble graphite. I made the shinier parts using harder pencils. I was interested in this process of covering, masking.” I tell her that in some countries the faithful cover the bones of saints with gold leaf and jewels. She says she finds that interestingly similar to what she had in mind with this piece. But the objects that make up Remains are no bones: a closer look reveals that they’re actually shaped like bullets, fired projectiles, broken sabres, arrowheads and twisting tongues. “There’s no particular symbolism in these objects,” Flessa tells me as I attempt to give an anti-war meaning to the work. “These forms were made intuitively, and all I wanted was to create a sense of timelessness, where something ancient that looks like a fossil or a prehistoric cutting stone also includes elements from other times.”

Despina Flessa, Remains (detail), graphite on clay, variable dimensions, 2015. Photo by Costas Christou.

Despina Flessa, installation view. Photo by Costas Christou.

This element of time-bending is evident in the rest of the works as well. For example, Flessa’s works on paper feature depictions of nature copied from different artistic styles and periods, from 18th-century bucolic Arcadias to 20th-century photography. And I say copied, because they’re actually xerographic prints —basically, photocopies. “I find these images and I edit them a bit, then I print them before transferring the graphite from the xerographic print on the work. What I end up with is not a print but the remains of the print.” These printer-remains then melt into dense surfaces of graphite that are disproportionately larger than the image itself. Using the same water-soluble graphites, Flessa covers the entire surface of the paper, both front and back; as a result, the paper shines with a metallic sheen, but it also curves and bends under its own weight. “What I wanted to achieve here is a kind of insulation, like sealing every pore of the paper with the graphite. But there’s nothing obsessive about this. It’s not about the time spent making it or being obsessed with getting a task done. It’s more about creating this mystery: what kind of image could be hidden under this surface? That’s the question I wanted to pose here.”

Despina Flessa, Folding landscape , graphite print and graphite on paper, 58 x 22 cm, 2015.

Despina Flessa, Folding landscape (detail), graphite print and graphite on paper, 58 x 22 cm, 2015. Photo by Costas Christou.

Despina Flessa, Landscape tableaux, graphite on wood veneer, 280 x 400 cm, 2015. Photo by Thomas Gerasopoulos.

As they escape their two-dimensional plane, these curving paper works seem to move towards the viewer and create a space around the images they carry. The same kind of movement can be seen in Landscape Tableaux (2015), a four-meter-wide composition of thin wooden veneer sheets, once again covered in graphite. With this work, Flessa wanted to create the impression of a canvas melting off the wall, a gesture that resonates with the sense of weight and gravity that can be found in all the works of the series, the most telling of which is Fold (2015): a one-meter-long piece of paper completely covered in graphite and suspended from the wall at a very low height, in many ways reminiscent of Richard Serra’s To Lift (1967). But where Serra’s sculpture has an upward movement and assured firmness, Flessa’s Fold is seen bending downwards in abandonment and release. Encumbered by its many layers of graphite and a kind of “dense writing that says nothing” as Flessa describes it, the paper surrenders to the weight of its own history, saturated by the noise and iterations of narratives told by others. And just like history itself, what was once light and upright now inevitably hunches and withers under its own significance.

Despina Flessa, Fold, graphite on paper, 100 x 80 cm, 2015. Photo by Costas Christou.

Despina Flessa, Fold, graphite on paper, 100 x 80 cm, 2015. Photo by Costas Christou.