The Fractal Beauty of Barbara Wildenboer's Chaotic Paper Constructions

Words by Eric David

Location

The Fractal Beauty of Barbara Wildenboer's Chaotic Paper Constructions

Words by Eric David

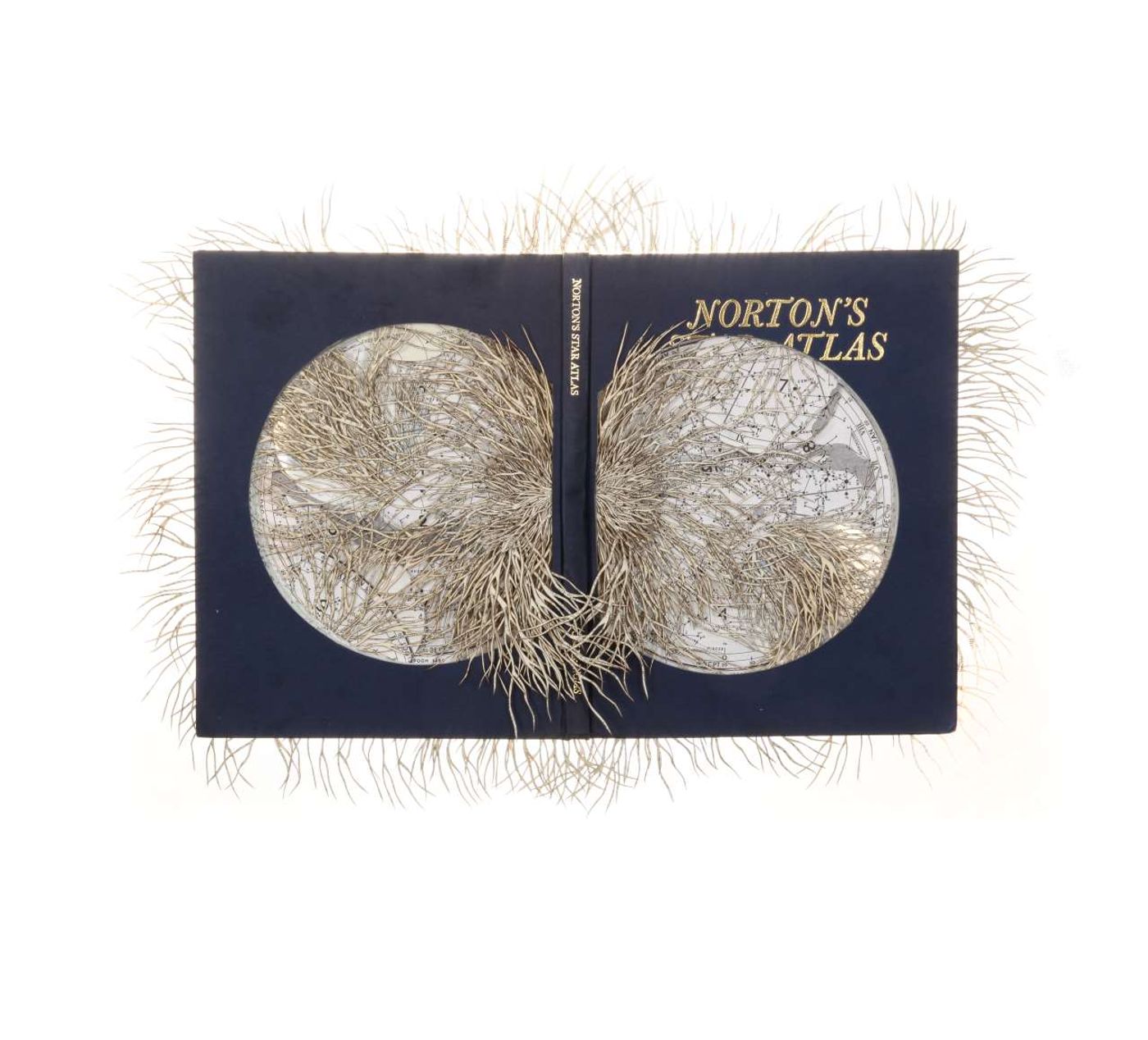

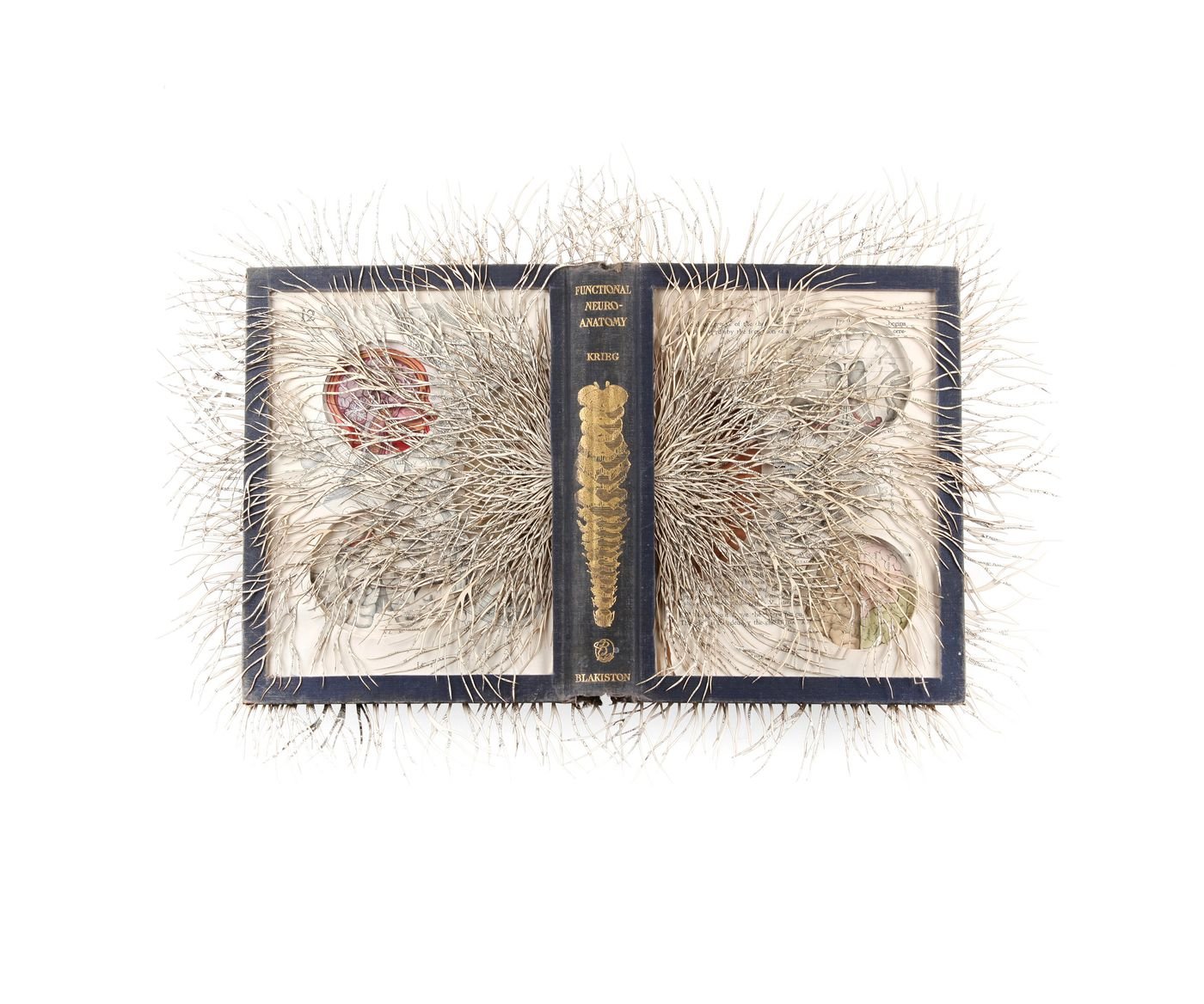

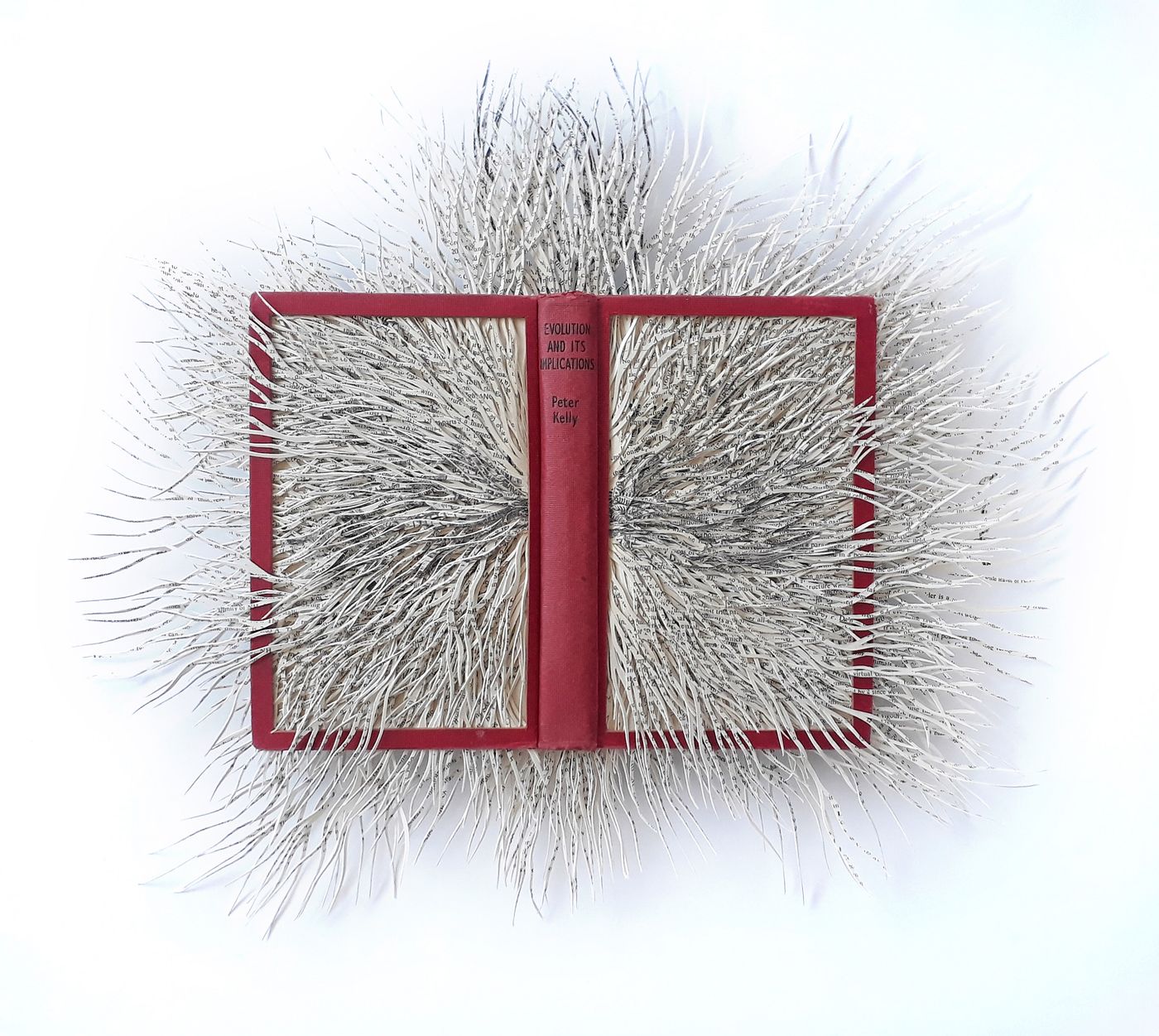

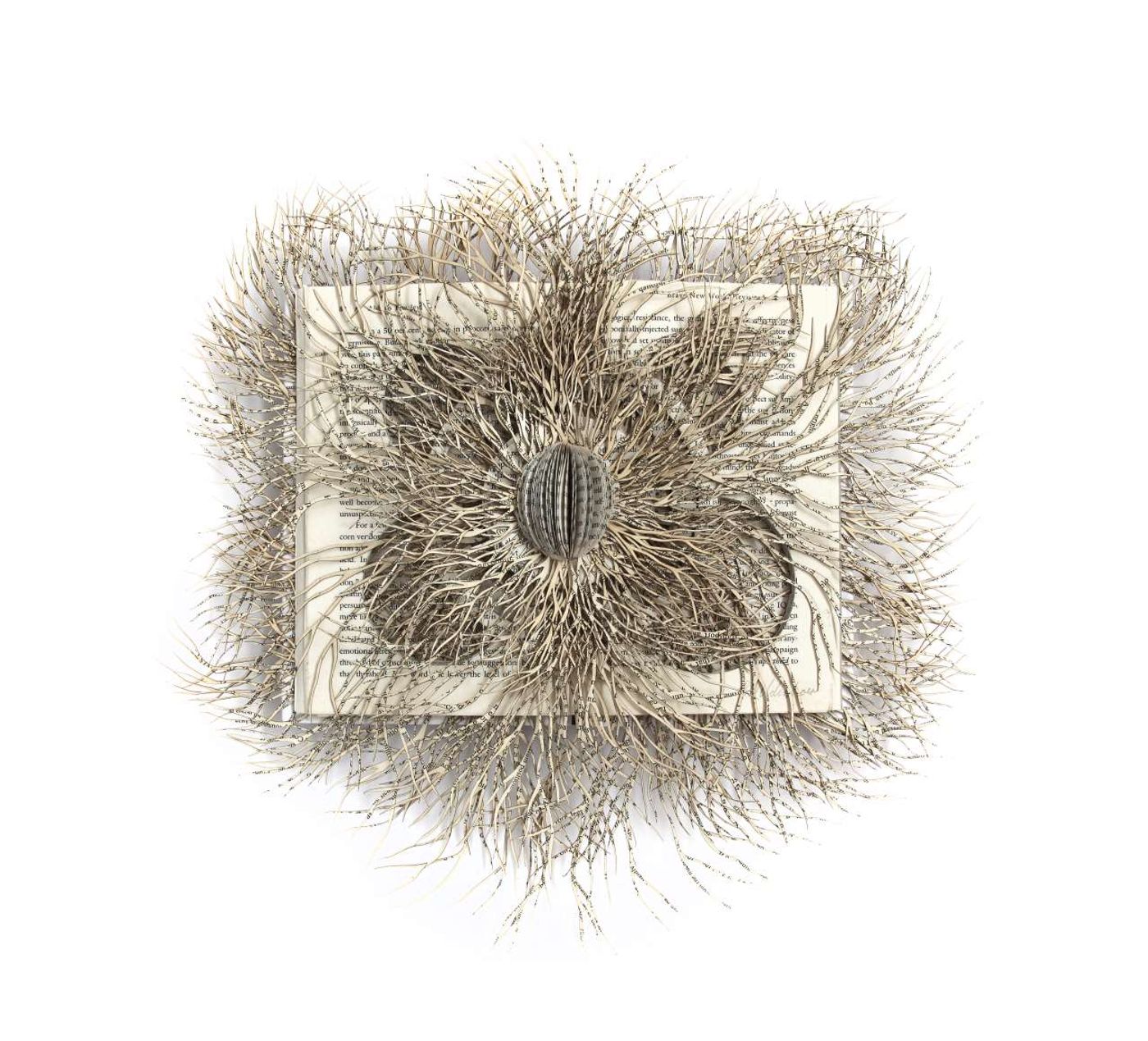

In The Library of Babel, Jorge Luis Borges talks about the universe in the form of a vast library whose infinite number of hexagonal galleries contain all possible existing and future books. South African artist Barbara Wildenboer’s ongoing oeuvre could also be likened to Borges’ infinite library both in her use of an ever expanding number of books as raw material and in her willingness to address the information overload of the modern internet era. In the ongoing series Library of the Infinitesimally Small and Unimaginably Large for example, Wildenboer appropriates books and atlases transforming them into mesmeric paper sculptures whose intricate physicality is as engaging as the written content it has replaced.

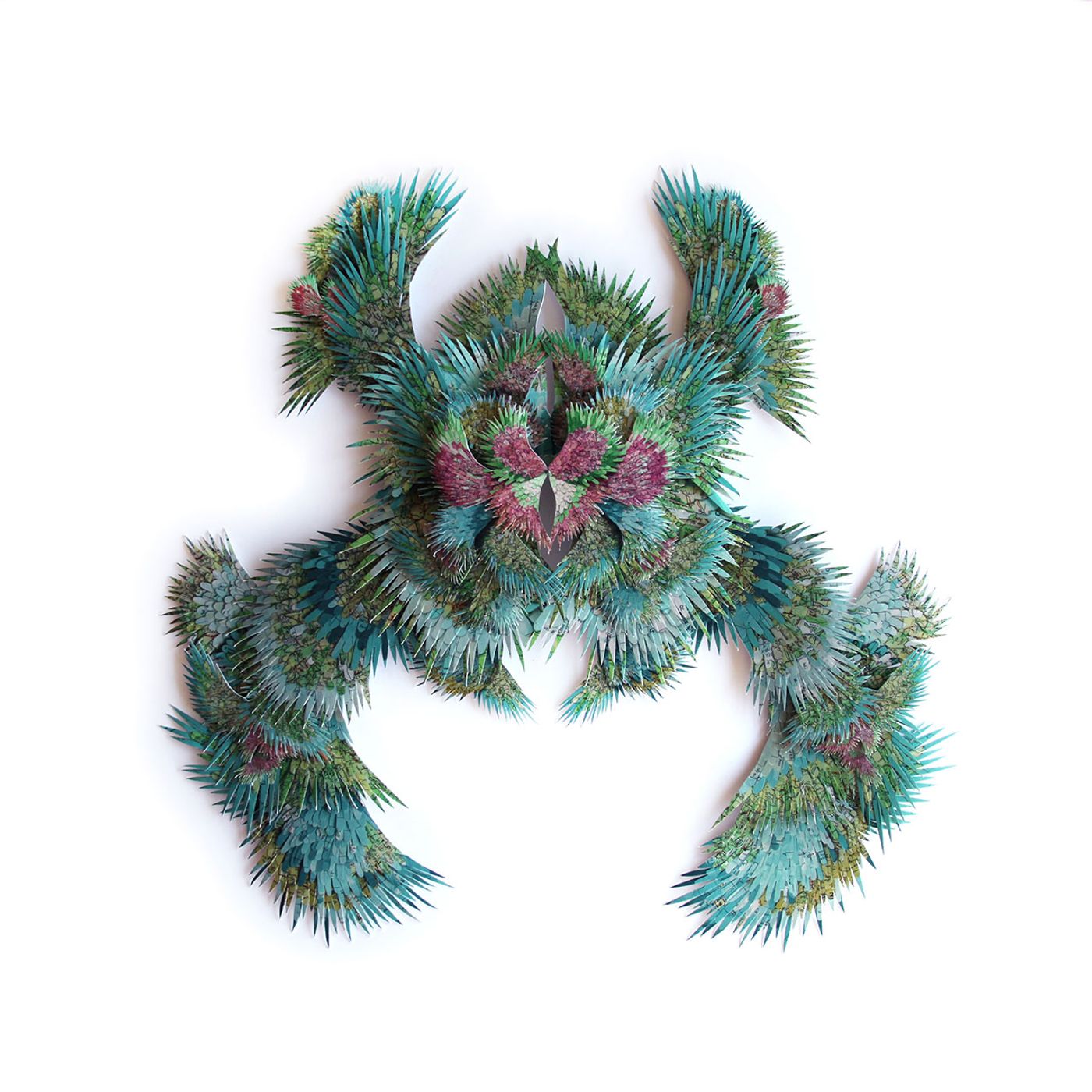

In her series Folly and Residue & Excess, torn-off pages from books and magazines are reconfigured into three-dimensional, biomorphic collages that seem to turn chaos into order, conveying modern society’s rampant consumerism, wastefulness and disconnection from the natural world, as well as hinting at the interconnectedness of all living things. Uniting all her work is Wildenboer’s ability to weave together visual narratives in which the old and new co-exist in a tentative balance. Yatzer recently caught up with the artist to discuss her ongoing projects, the prolific use of books in her work, and her fascination with fractal geometry.

(Answers have been condensed and edited for clarity.)

Barbara Wildenboer, Relics and remains, from 'Residue and Excess' series. © Barbara Wildenboer.

Barbara Wildenboer, Totem II, from 'Towers of Babel' series. © Barbara Wildenboer.

Barbara Wildenboer, The Rules of Fair Play. © Barbara Wildenboer.

Barbara Wildenboer, The Terrarium Dream. © Barbara Wildenboer.

Barbara Wildenboer, Totem I, from 'Towers of Babel' series. © Barbara Wildenboer.

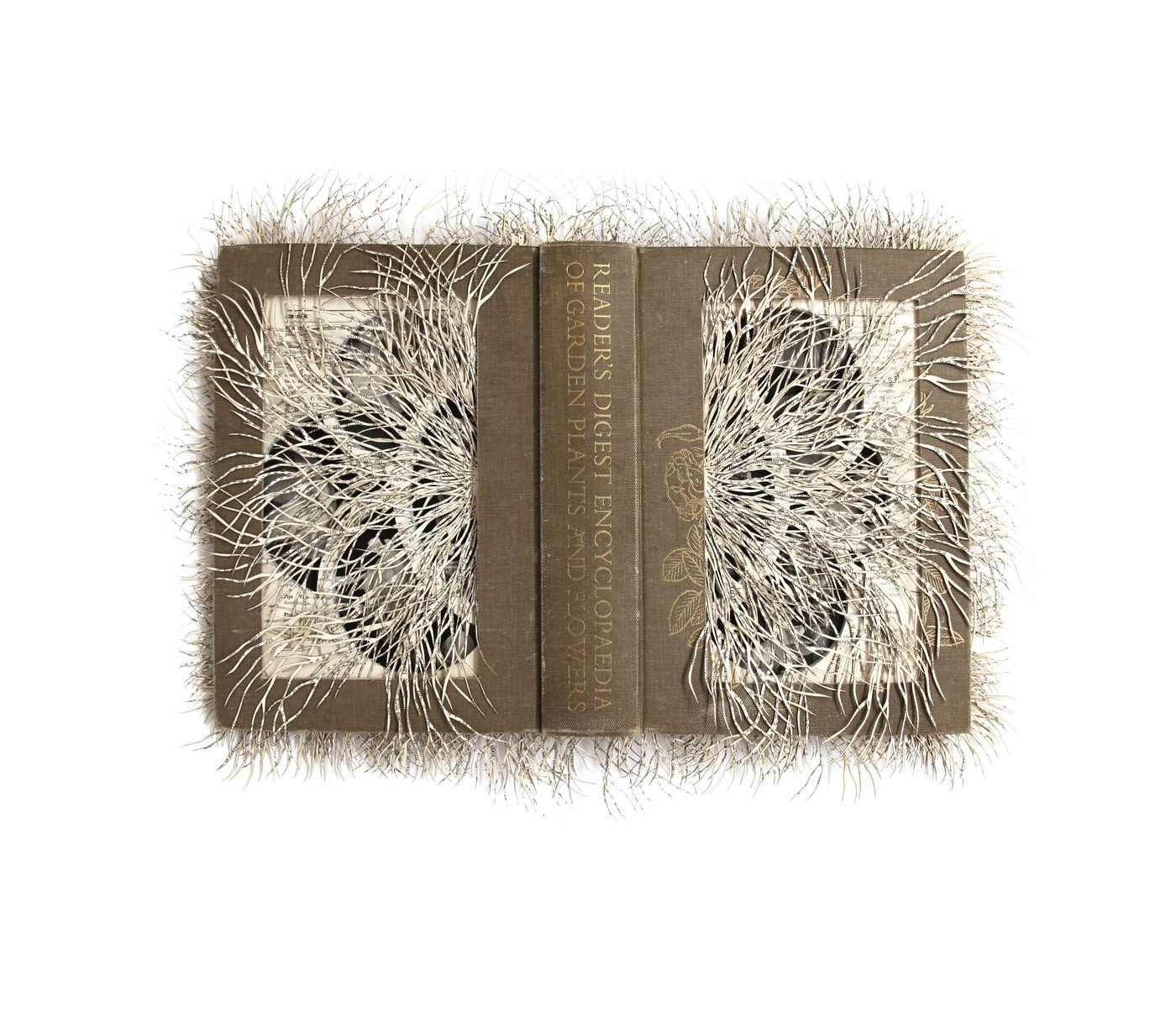

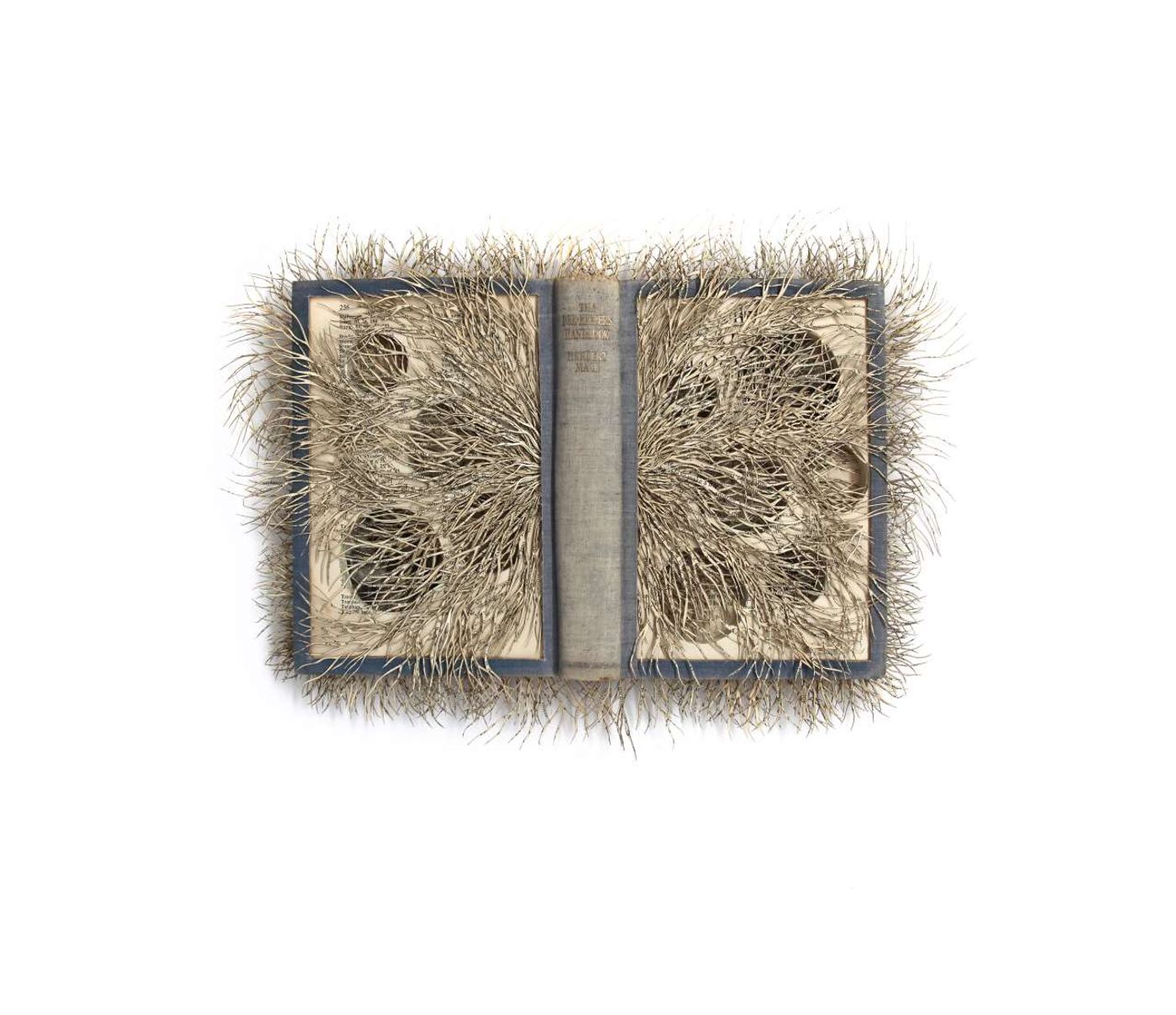

Barbara Wildenboer, Cross Pollination III, 2015, from 'Library of the Infinitesimally Small and Unimaginably Large' series. © Barbara Wildenboer.

Take us back to your artistic beginnings. What prompted or inspired you to become an artist?

Even as a child I was always interested in the way paper can be manipulated. Early influences were definitely a love for pop-up books, and later, as an art student, the Surrealist and Dadaist collages of Hannah Hoch and Max Ernst. I was really interested in how both artists’ work spoke of a collective unconscious with its common dream imagery through the use of newspapers and magazines, catalogues, fashion brochures as well as maps, charts and scientific encyclopedias. Their paper works, use of collage and application of chance and ‘happy accidents’ has greatly influenced me.

The intricate assemblage of your collages and the materials you use suggest that besides being an artist you also take on the roles of curator and editor. Is that a reaction or pushback to the excess of information fueled by the digital age we live in?

I am always in the process of ‘collecting’. I do this either physically by gleaning images from books using blades or by using my camera. I have built up archives of images over the years. My studio is filled with cardboard filing boxes with different labels. These contain images ranging from pictures of war, to botanical images, to cut-outs of Renaissance nudes. Of course I would be able to source these images directly from the internet with the ease of a Google search but there’s something magical about the haptic process of physically gathering material from tangible objects found by chance that I find very engaging.

Barbara Wildenboer, Until the Sun Dies, from 'Library of the Infinitesimally Small and Unimaginably Large' series. © Barbara Wildenboer.

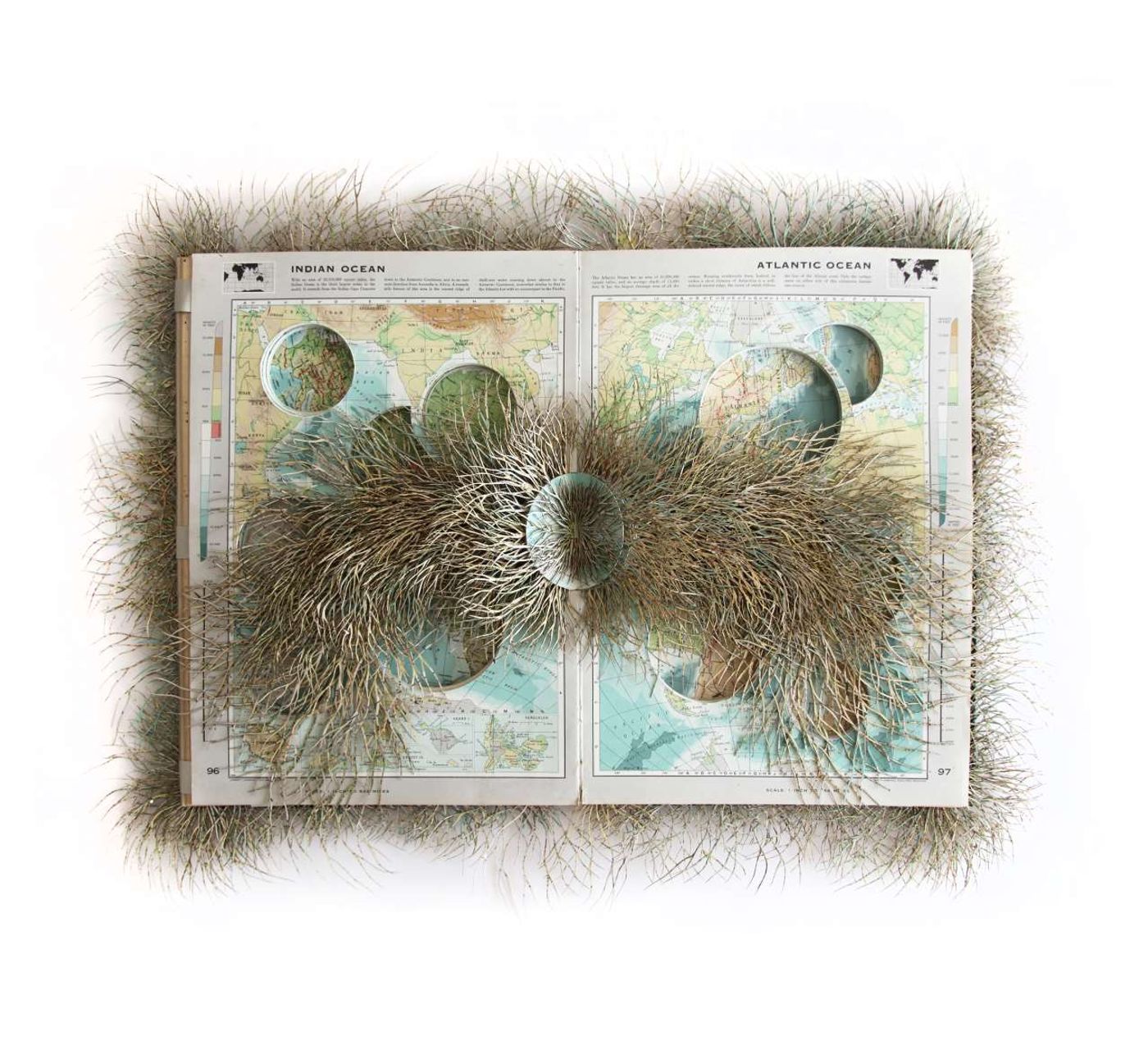

Barbara Wildenboer, from 'Library of the Infinitesimally Small and Unimaginably Large' series. © Barbara Wildenboer.

Barbara Wildenboer, from 'Library of the Infinitesimally Small and Unimaginably Large' series. © Barbara Wildenboer.

Barbara Wildenboer, The Senses of Animals and Men, from 'Library of the Infinitesimally Small and Unimaginably Large' series. © Barbara Wildenboer.

Barbara Wildenboer, Dark Paradise II, 2014, from 'Library of the Infinitesimally Small and Unimaginably Large' series. © Barbara Wildenboer.

You have embraced books both as a material that can be sculpted and as a source of raw material for your collages. Where does your interest in books and their appropriation come from? What do you want to convey?

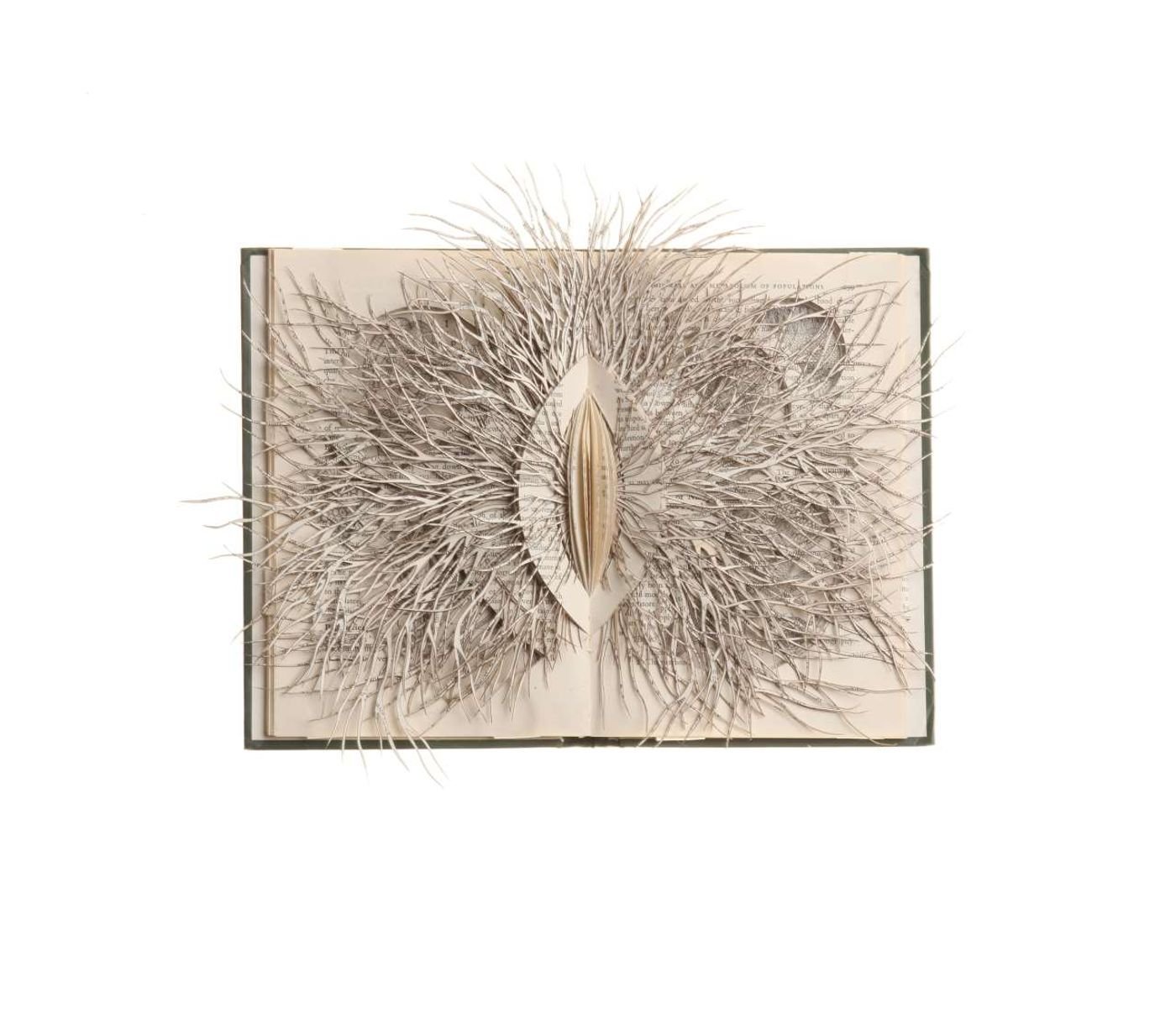

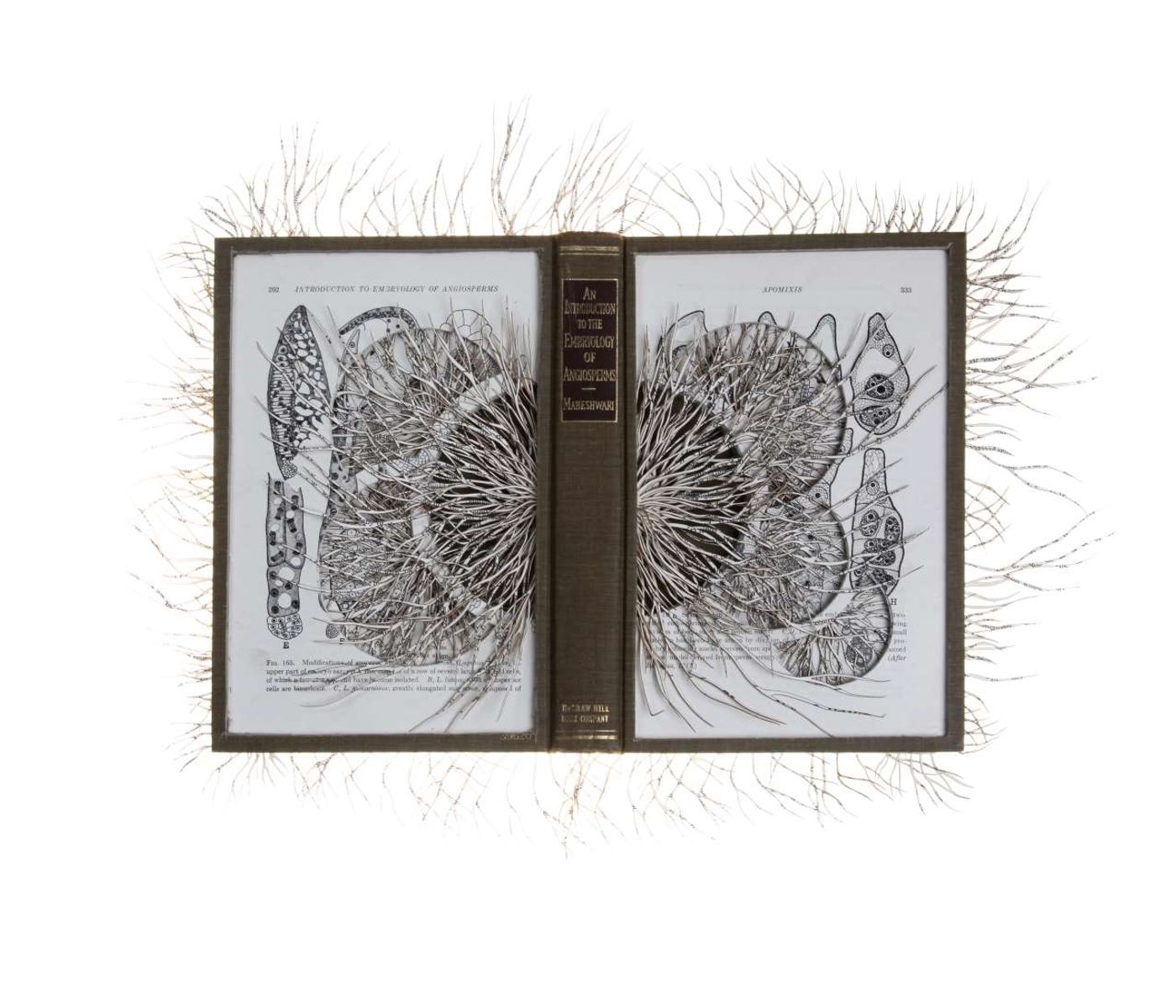

I have been working on the altered book series since 2011. It is an ongoing project entitled Library of the Infinitesimally Small and Unimaginable Large and was inspired by The Library of Babel by Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges. In this short story, Borges uses the library as a metaphor for the universe. I often make intertextual references in my paper works as well as think and speak easily in metaphors, even when it comes to commonplace everyday matters.Sometimes people react emotionally about the fact that I am apparently destroying books. Books have again and again been targets of censorship and book burning. I see my manipulation of book objects as a form of upcycling and a transformation of a book as a physical object, rather than a destruction of knowledge. The information contained in the book still continues to exist.

Barbara Wildenboer, from 'Library of the Infinitesimally Small and Unimaginably Large' series. © Barbara Wildenboer.

Barbara Wildenboer, Dark Paradise I, 2015, from 'Library of the Infinitesimally Small and Unimaginably Large' series. © Barbara Wildenboer.

Where do you source the books you use in your work? How does the books’ content influence the final artwork?

I source the books and maps from second hand bookshops and flea markets all over the world. In the selection process I not only consider the books for their physical characteristics such as typographical layout, size, wear, and paper quality, but also more specifically for their subject matter. Therefore the majority of the books are linked by the subject matter of fractal geometry.The altered book series also touches on the arguably uncertain future of printed books as a consequence of the increased popularity of new electronic digital alternatives.

Your work is characterized by an astounding level of detailing. How intensive and time-consuming is the creation of your artworks?

I use a combination of mostly analogue but also digital processes to create the collages, photo and paper constructions, and animated collage videos. Occasionally I make use of technology but most of the pieces are either partially or entirely hand cut. My working process has become so intertwined in my day to day life that it has become difficult to determine the amount of time spent on a single artwork.

Barbara Wildenboer, from 'Library of the Infinitesimally Small and Unimaginably Large' series. © Barbara Wildenboer.

Barbara Wildenboer, from 'Library of the Infinitesimally Small and Unimaginably Large' series. © Barbara Wildenboer.

Barbara Wildenboer, Relics and remains installation view. Photo © Barbara Wildenboer.

Barbara Wildenboer, Relics and remains installation view. Photo © Barbara Wildenboer.

Barbara Wildenboer, Relics and remains 4, from 'Residue and Excess' series. © Barbara Wildenboer.

Take us through your creative process. Do you meticulously plan everything beforehand or is there a strong element of spontaneity in the artworks you craft?

Early exposure to psychology and literature studies had an enormous impact on my thought processes and the conceptualising of my work. I work intuitively and cerebrally and am very interested in the active role the subconscious and chance plays in the creative process. There is a fine interplay between coming across the right picture book in a pawn shop, the way in which I deliberately choose the particular visual images to cut out, the way in which the cuttings fall in combinations on the floor, and the connections that I then notice between the various images. For me, there is an almost magical element to the process and I feel at times almost as if the collages make themselves and that I am merely facilitating the process.

Your work is pervaded by a distinct iconography of organic forms, both conspicuous and intimated, including allusions to human anatomy. What is the conceptual and aesthetic motivation behind the use of such representations?

A lot of the organic fractal shapes I use in my work are reminiscent of organs or body parts. I also often refer to earth in anthropomorphic terms. I want to emphasise the interconnection between all living things and the symbiotic relationship between humans and the natural world. This becomes particularly evident when observing fractal patterns that seem to be repeated across different life forms and natural phenomena.

Barbara Wildenboer, Holy Smoke I, 2018, from 'Folly' series. © Barbara Wildenboer.

Barbara Wildenboer, Holy Smoke II, 2018, from 'Folly' series. © Barbara Wildenboer.

Barbara Wildenboer, Folly IV, 2018, from 'Folly' series. © Barbara Wildenboer.

Barbara Wildenboer, Folly I, 2018. © Barbara Wildenboer.

Barbara Wildenboer, Recapitulation Theory III. © Barbara Wildenboer.

Barbara Wildenboer, Recapitulation Theory I. © Barbara Wildenboer.

Barbara Wildenboer, Recapitulation Theory II. © Barbara Wildenboer.

Your work is distinguished by a very structured and figurative sensibility that is nevertheless underpinned by a mesmerizing sense of chaos. What is the significance of this harmonious dissonance?

My father was a professor of mathematics at the University of Pretoria in South Africa so maths and science were always in the foreground in our home. He made me aware of the concept of mathematics as a language and especially as the language of nature. Fractal geometry and Chaos Theory in particular became a great source of fascination and interest to me — the way that chaos explores the transitions between order and disorder.

The chaos/order dichotomy also forms part of a personal narrative. Ten years ago my life was very chaotic. Friends would tease me that my art had to be so orderly and precise to provide a counterpoint to the chaos in my personal life. Perhaps that was true and, if so, it was a successful strategy. Over the last decade, the structure and order that was in my art has obviously spilt over into my personal life. The result of this is that I have, over the course of time, started to work more experimentally and less rigidly in my art process. There is a constant process of aiming at a balance between too much order and too much chaos.

© Barbara Wildenboer.

Barbara Wildenboer, Mixed-species assemblages VI. © Barbara Wildenboer.

There seems to be an overarching theme of environmental peril in your work. Where did your ecological concerns stem from? What do you believe is the role of art in addressing such important issues?

In most of my work, I create in one way or another a reference to environmental questions. The collages playfully reference human folly and the potential consequences of human impact on the earth’s geology and ecosystems.I have always found huge appeal in the work of Dutch Renaissance artist Hieronymus Bosch, especially his triptych The Garden of Earthly Delights. Not just the rich detail, but also the various intertextual references, from mythological stories to alchemical processes. Recently, I was privileged to see the original triptych in the Museo del Prado in Madrid. Bosch’s depiction of folly, or rather of human foolishness and madness, in particular, is a theme that really interests me at the moment.I think people are beginning increasingly to understand that environmental ethics are just as important as social economic aspects for defining what it means to be human.

Barbara Wildenboer, Mixed-species assemblages installation view. © Barbara Wildenboer.

What are you working on right now? Any exhibitions under way?

My next solo exhibition entitled Eros/Thanatos will open at the Everard Read gallery in Johannesburg on the 15th of November. I will also be having a solo exhibition entitled Folly at Everard Read’s London location in March 2019.

Paper sculpture detail. © Barbara Wildenboer.