Simon Birch's The 14th Factory: A World in Disorder

Words by Eric David

Location

Los Angeles, California, United States

Simon Birch's The 14th Factory: A World in Disorder

Words by Eric David

Los Angeles, California, United States

Los Angeles, California, United States

Location

Taking up over 15,000 square meters in an empty industrial warehouse in Lincoln Heights on the outskirts of downtown Los Angeles, Simon Birch’s ambitious project, The 14th Factory, is an immersive, multi-media art experience that takes visitors on an enthralling ride through an otherworldly cosmos of dystopian character and transcendental possibilities.

Although the venue is a pop-up art space, the exhibition was a long time in the making, having been conceived eight years ago, right after the British-born, Hong Kong-based artist was diagnosed with cancer and given six months to live. Organized without any institutional support through a non-profit global artist collective that Birch set up and financed with all his savings, the exhibition was created in collaboration with 20 architects, filmmakers and multimedia artists as a “new, independent paradigm for socially-engaged art.” On a personal level, asides from proclaiming a tumultuous journey from a self-confessed ‘hooligan’ in the English Midlands to a self-taught artist in Hong Kong, it also serves as Birch’s calling card announcing his induction into the global art world in the most monumental fashion.

The 14th factory, front entrance. Photo by Gloria Yu.

anothermountainman, Standard, 2016. 1 large flag, 14 smaller flags, Nylon. Photo by Gloria Yu.

The 14th factory, Entry wall. Photo by Gloria Yu.

Doug Foster and Simon Birch, The Dormouse, 2015. Two-channel video. Photo by Gloria Yu.

The show takes its name from the quarter in Guangzhou (which the Europeans called Canton) known as “Thirteen Factories”, a de facto ghetto where foreign merchants were obliged to base their operations in order to trade with China for nearly 150 years during the 18th and 19th centuries. With each nation occupying its own “factory” and fiercely competing against one another, and in light of its violent dissolution during the Opium Wars and the subsequent establishment of extraterritorial treaty ports such as Hong Kong, for Birch the quarter is emblematic of a strife-ridden world where violent conflicts both stem from and result in shifting borders and fluctuating barriers.

To get this point across as well as shut out the outside world, upon entering the exhibition visitors are plunged into darkness where they slowly begin to make out a scene of chaos and destruction. Making their way to the center of this space, they bewilderingly step into the last scene in Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey. Titled “The Barmecide Feast” and built in collaboration with Birch’s architect friend Paul Kember—whose uncle was fittingly Kubrick's chief draftsman—and KplusK Associates, the installation is an exact replica of the bedroom where at the end of the movie astronaut Dave Bowman finds himself lying in bed and is summarily transformed into a star baby. As Birch explains, this work is a “perfect symbol and metaphor for the entire project”, namely a journey of upheaval and turbulence that precipitates a process of transcendence and transformation.

Detail from The Meteor collection, concept by Simon Birch co-designed by Taylor Philips Hungerford and KPlusK associates , 2013-17. Mixed media installation: Masonite, wood, foam and paint. Photo by Gloria Yu.

Detail from The Meteor collection, concept by Simon Birch co-designed by Taylor Philips Hungerford and KPlusK associates , 2013-17. Mixed media installation: Masonite, wood, foam and paint. Photo by Gloria Yu.

The Meteor (sculpture), Concept by Simon Birch co-designed by Taylor Philips Hungerford and KPlusK associates , 2013-17. Mixed media installation: Masonite, wood, foam and paint. Photo by Gloria Yu.

'Meteor' sculpture, work in progress. Photo by Gloria Yu.

What follows is a labyrinthine scenography of interlinked, interior and exterior spaces comprised of video, installation, sculpture, paintings and performance, an unknown territory which the visitor, much like the movie’s protagonist, is invited to venture into.

One of the most impressive works is undoubtedly “Clear Air Turbulence”, a sculptural installation featuring several salvaged airplane wings and tail fins protruding out of a rectangular pool of dark water. Initially appearing as shark fins, there is something quite menacing and disturbing as the scene alludes to both an airplane graveyard and a site of some kind of catastrophe. Moreover, the dimensions of the pool are identical to those of Kubrick’s monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey—which an observant cinephile may have noticed was missing from the recreation of the movie’s final set—representing humanity’s epic, and many times violent, transitions in its evolutionary path.

Simon Birch and KplusK associates, The Barmecide Feast, 2016. Wood, steel, acrylic, light, furniture, objets d’art. Photo by Gloria Yu.

Simon Birch and KplusK associates, The Barmecide Feast, 2016. Wood, steel, acrylic, light, furniture, objets d’art. Photo by Gloria Yu.

Simon Birch and KplusK associates, The Barmecide Feast, 2016. Wood, steel, acrylic, light, furniture, objets d’art. Photo by Gloria Yu.

The depiction of violence or its aftermath that is palpable in “Clear Air Turbulence” is shared by many of the exhibition's installations. Take for example the “The Crusher”, where 300 pitchforks hang menacingly from the ceiling, or the six-channel video named “Inhumans”, a collaboration with photographer and filmmaker Wing Shya portraying a horde of Chinese men punching each other in slow motion. In another multi-screen video installation, “Inevitable”, co-created with filmmaker and art director Eric Hu, visitors can watch a stuntman graphically crash Birch's red Ferrari on giant screens as well as gawk at close-up pictures and pieces of the wreckage on display.

Providing some respite from the gruesome sensibility of these works, the show also includes pieces of a more poetic nature such as “Tannhauser”, where visitors are engulfed by floor-to-ceiling video projections of Hong Kong’s gargantuan residential towers, an experience both voyeuristic and disorienting as the camera moves up and down the facades, as well as "This Brutal House", a video filmed by Irish director Scott Carthy that documents a group of New York street dancers swirling mid-air in slow motion, their gravity-defying, rotating bodies reminiscent of the space waltz scene in Kubrick’s iconic film. Works like these ensure that, despite the dystopian iconography and the menacing undertones, Birch’s The 14th Factory is neither pessimistic nor bleak. On the contrary, its collaborative nature points to our shared humanity being the key to our transcendence.

Simon Birch, Garlands, Lily Kwong and KplusK associates, 2016-17. Earth, grass, live flowers, steel, wood, swings. Installation view. Photo by Gloria Yu.

Simon Birch, Garlands, Lily Kwong and KplusK associates, 2016-17. Earth, grass, live flowers, steel, wood, swings. Installation view. Photo by Gloria Yu.

Simon Birch, Garlands, Lily Kwong and KplusK associates, 2016-17. Earth, grass, live flowers, steel, wood, swings. Installation view. Photo by Gloria Yu.

Simon Birch, Jubilee, 2015-17. Various paintings and drawings, Oil on canvas. Photo by Gloria Yu.

Scott Carthy and Simon Birch, This Brutal House, 2015. Single-channel video. Photo by Gloria Yu.

Pitchforks for 'The Crusher', work in progress. Photo by Gloria Yu.

Simon Birch, The Crusher, 2016-17. Site-specific installation, 300 pitchforks. Wood, steel, paint. Photo by Gloria Yu.

Simon Birch, The Crusher, 2016-17. Site-specific installation, 300 pitchforks. Wood, steel, paint. Photo by Gloria Yu.

Eric Hu and Simon Birch, The Inevitable, 2015. Editing assisted by Touches. Six-channel video. Photo by Gloria Yu.

Eric Hu and Simon Birch, The Inevitable, 2015. Editing assisted by Touches. Six-channel video. Photo by Gloria Yu.

Eric Hu and Simon Birch, The Inevitable, 2015. Editing assisted by Touches. Six-channel video. Photo by Gloria Yu.

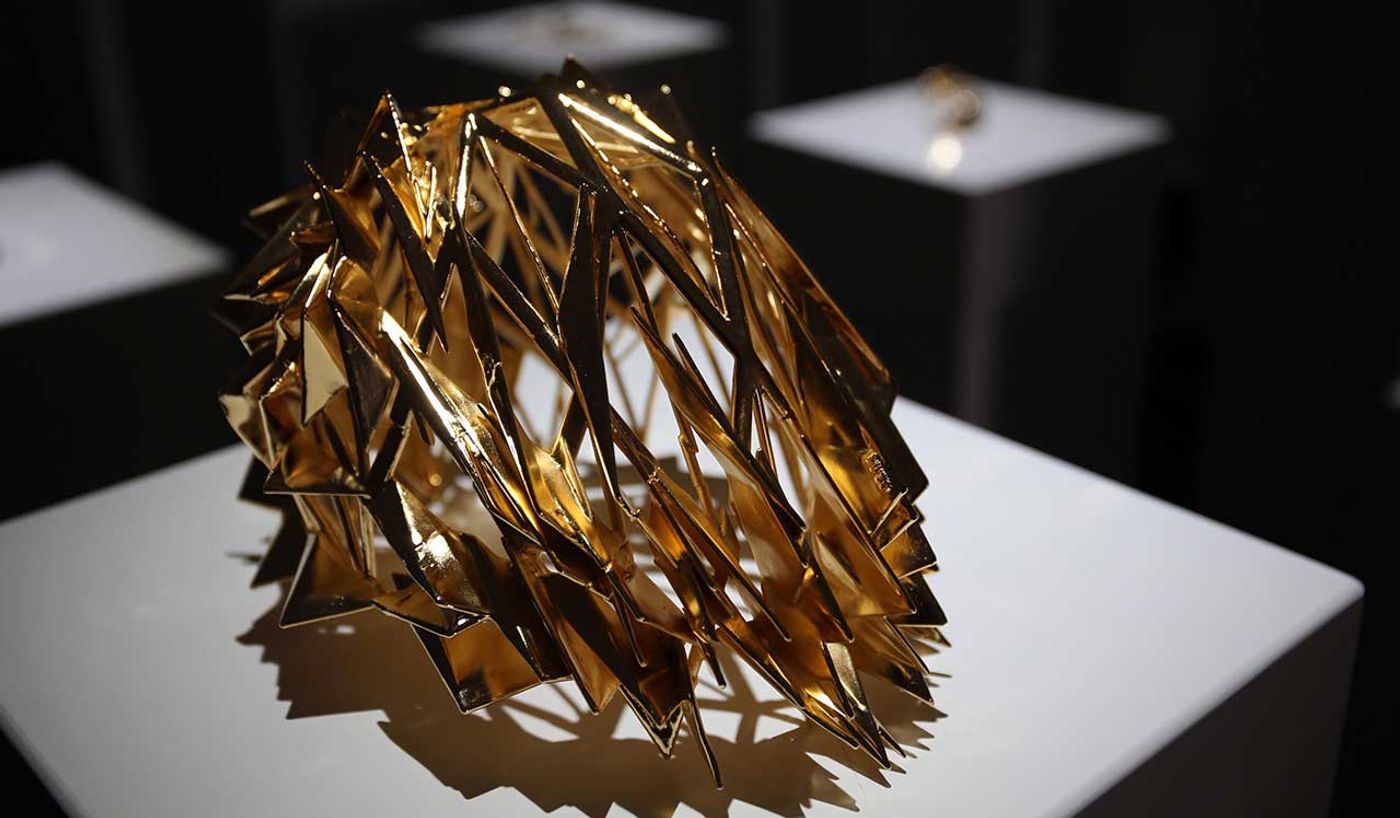

Simon Birch, Gloria Yu, Gabriel Chan and Jacob Blitzer, Hypercaine, 2016. Crowns. Brass, nylon, gold plate, marble, wood, stone, metal. Exhibition view. Photo by Gloria Yu.

Simon Birch, Gloria Yu, Gabriel Chan and Jacob Blitzer, Hypercaine, 2016. Crowns. Brass, nylon, gold plate, marble, wood, stone, metal. Exhibition view. Photo by Gloria Yu.

Simon Birch, Tannhauser, 2016. Filmed by Scott Sporleder, Edited by Jennifer Russell. 4-channel video. Photo by Gloria Yu.

Simon Birch , The sky was aquamarine, stroked with clouds. She could smell the grass and taste the scent of small, crushed flowers, 2015. Oil on canvas. Audioscape by Gary Gunn. Photo by Gloria Yu.

Movana Chen, Knitting Conversations, 2011-ongoing. Paper. Photo by Gloria Yu.

Sara Tse and anothermountainman, Standard II, 2016. Porcelain casts of cloth flags. Installation view. Photo by Gloria Yu.

Simon Birch, The Unrevealed, 2016. Found antique plough plated in gold. Photo by Gloria Yu.

Simon Birch, The Unrevealed, 2016. Found antique plough plated in gold. Photo by Gloria Yu.

Simon Birch, Untitled, 2016. Assembled fragments of a 1980 Ferrari, Metal, paint. Photo by Gloria Yu.

Simon Birch Drawings. Photo by Gloria Yu.