Indian Heritage Meets Avant-Garde Design: A Conversation with Vikram Goyal

Words by Eric David

Location

Indian Heritage Meets Avant-Garde Design: A Conversation with Vikram Goyal

Words by Eric David

Standing at the forefront of contemporary Indian design, New Delhi-based designer Vikram Goyal is renowned for his ability to weave India’s rich heritage into a modern, avant-garde visual language. Rooted in India’s historical and cultural narrative, Goyal's work draws inspiration from a wide range of artistic traditions, from the intricate Pichwai paintings and majestic Mughal architecture to the geometric elegance of Art Deco and the organic beauty of natural forms. These influences, paired with his keen interest in global design culture, anchor his practice, which deftly balances a reverence for the past with an exploration of contemporary, sculptural abstraction. As Goyal himself explains, “Every object has the right to tell its story”, a philosophy that drives his creations and connects them to India's storied past.

Goyal’s practice is defined by his deep respect for intergenerational craft techniques such as repoussé (his studio’s signature technique of hammering designs into metal from the reverse side), pietra dura, and hollowed joinery. His pieces—sculptural, tactile, and deeply expressive—are simultaneously in conversation with both past and present. Exhibiting globally, including at Milan’s Nilufar Gallery (where he was the first Indian designer to be showcased) and Future Perfect in Los Angeles, his work demonstrates an enduring commitment to craftsmanship while forging new possibilities for Indian design. On the occasion of Goyal’s participation at the upcoming PAD London, where he will unveil his latest creations with Nilufar Gallery, Yatzer recently caught up with the designer to talk about his studio practice, his passion for metalwork, and his latest venture, Viya, which aims to bring contemporary Indian craftsmanship to a wider audience.

Answers have been condensed and edited for clarity.

Vikram Goyal.

Courtesy of Vikram Goyal.

Where does your fascination with craft practices, and metalwork in particular, originate from?

I grew up in New Delhi and spent a lot of my childhood in Rajasthan. Both these cities are areas of great cultural legacy and the visual arts. Being there during my formative years forged an insatiable interest in India's culture, architecture and creativity. Craft was a crucial part of that language, and with that was metalwork. When I returned to India in 2000 after spending several years in the US and Hong Kong, I stumbled upon a master artisan, a craftsman named Ramesh, and together we began to experiment with the potential of this metal.

It was a moment that marked the beginning of my adventures with craft. I knew I wanted to work with a traditional material and brass. It’s something integral in our everyday life through ritual vessels and decorative temples, and felt instinctively right. It is prolific within India’s craft heritage, with many artisans possessing great skill and expertise. I also loved its sheen and versatility.

Morvi Cabinet. Brass. 2438 x 457 x 914 mm.

Towering Banyan Screen. Brass. 1041 x 457 x 2438 & 914 x 457 x 2159 mm.

Palazzo Coffee Table. Brass. 2388 x 508 x 406 mm.

Image courtesy of Vikram Goyal.

Sprawling Prism Dining Table. Brass/Veneer. 3048 x 1067 x 762 mm.

Curve Coffee Table. Brass. 1524 x 914 x 406 mm.

Image Courtesy of Vikram Goyal.

Vikram Goyal Studio at PAD Design + Art. Nilufar Gallery.

Mesa Console. Brass and Black Porter Stone, Repousse and Hollowed Joinery. 124" L x 24" D x 42" H.

Image courtesy of Vikram Goyal.

Vikram Goyal Studio at PAD Design + Art. Nilufar Gallery.

Mesa Console (detail). Brass and Black Porter Stone, Repousse and Hollowed Joinery. 124" L x 24" D x 42" H.

Image courtesy of Vikram Goyal.

Artisans at work at Vikram Goyal Studio in New Delhi.

Courtesy of Vikram Goyal.

How do you balance preserving traditional Indian craftsmanship with introducing innovative techniques and contemporary design elements?

I'm neither a trained designer nor an artisan. My intervention comes from what we describe as the Karkhana workshop model [ in the context of Indian crafts, Karkhana refers to a traditional workshop or production system where skilled artisans work collectively under the guidance of a master craftsman ]. At our studio, we are a family of artisans, product designers, architects, engineers and production managers who all sit under one roof and experiment. While our artisans have traditional metalworking skills, some of which are intergenerational, we encourage them to push the boundaries, with the vision to develop a new design language. Being in the same space allows us to be collaborative, we can sample and refine—something that’s not possible with external collaborators.

Tell us a bit more about the Karkhana model. Why did you choose it, and what are the challenges of managing such a large team?

We chose this model because it facilitates a kind of cohesiveness which is ideal for experimentation and stretching the boundaries of a particular material. It allows us to sample and scale. Even with such a large team of artisans, the only challenges are those based on mindset—helping craftspeople evolve from an informal practice to a more formalised professional setting.

Vikram Goyal Studio at PAD Design + Art. Nilufar Gallery.

Flow Mirror. Brass, Repousse. 46" W x 10" D x 72" H.

Image courtesy of Vikram Goyal.

Vikram Goyal Studio at PAD Design + Art. Nilufar Gallery.

Flow Mirror (detail). Brass, Repousse. 46" W x 10" D x 72" H.

Image courtesy of Vikram Goyal.

Could you walk us through your creative process? Do you design every detail in advance, or is there room for experimentation during the making process?

Once we come up with an idea, our design team begins work on it to create a prototype which is then refined. This usually involves a lot of experimentation and can be a very long process, but the process definitely benefits from all elements of the supply chain being under the same roof, within the Karkhana.

How would you describe the evolution of your aesthetic since launching your career as a designer over 20 years ago?

When we first started, we were among the pioneers of a new design vernacular—‘India Modern’. We looked at different references from Indian architecture, culture and heritage, references from historic paintings and common symbols such as peacocks and lotuses. We created modern interpretations of these things and with that a new story, that was contemporary but still at its heart, Indian.Today, almost 20 years later, we work with international architects and designers. Our aesthetic has evolved into something much more contemporary, organic, and abstract, driven by creative curiosity and innovation. Rather than the Indian identity defining an aesthetic and technique, it now guides the technique but not the aesthetic. It’s a seismic shift.

Vikram Goyal Studio at Milan Design Week 2024. Nilufar Gallery.

Archimedes' Chandelier. Brass. 1245 x 762 x 2997 mm.

Image courtesy of Vikram Goyal.

To expand a little on what you’ve told us, you obviously draw from a wide range of references from Indian mythology, from Pachoi art and Mughal architecture to the Italian Renaissance, Art Deco, and Cubism. How do these diverse influences shape your work and how do you see a common thread among them?

Within our workshop there are three main material interventions. One is repoussé, which is the process of creating embossed artworks. It’s a technique that has really allowed me to bring life to all the various epochs, eras and stories that have always fascinated me.Hollowed joinery is the second, and is our own innovation that allows us to mould sheets of metal together to make three-dimensional objects. Our third intervention uses a lot of small parts that are welded together to create a larger, tapestry-like surface.

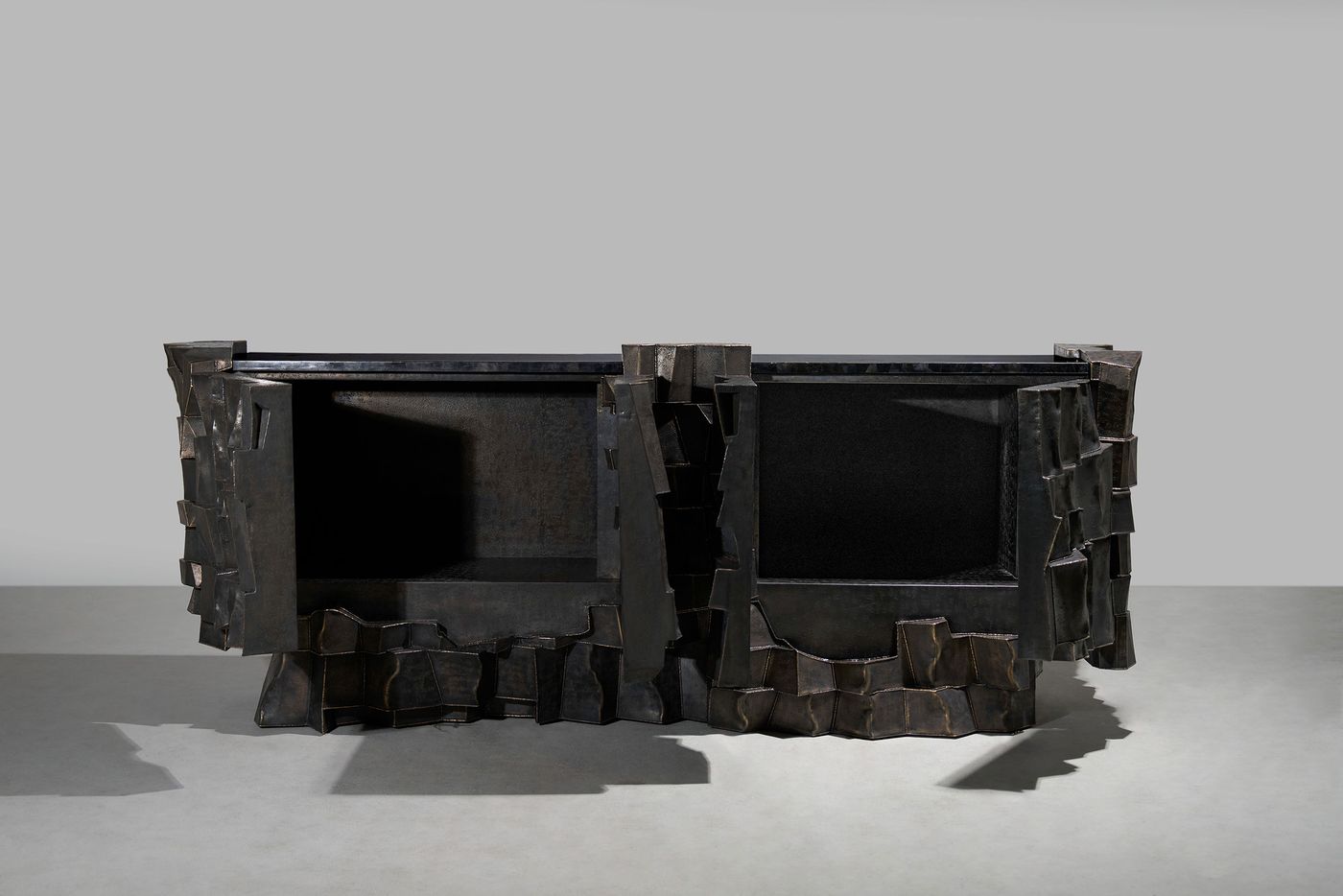

Vikram Goyal Studio at PAD Design + Art. Nilufar Gallery.

Shaded Graphite Cupboard. Brass and Black Porter Stone, Hollowed Joinery. 96" L x 24" D x 38" H.

Image courtesy of Vikram Goyal

Repoussé has truly allowed us to interpret Chinoiserie or Japone, while our other techniques have allowed us to express elements of art deco and cubism.

Now, as our focus is shifting to abstract and organic forms we continue to develop new skills and techniques that can reinvent and redefine the craft of metalwork.

Many of your works in brass are inlaid with semi-precious stones. What attracts you to these combinations, and what technical challenges do such designs present?

The process of pietra dura traditionally relates to the inlay of semi-precious gems into stone. We have transposed this craft into metal, inserting brightly coloured stones into our brass designs. It’s a process we have been perfecting for some time, as I love the diversity that it delivers in terms of both texture and colour. The ornamentation adds a fresh dimension to our aesthetic. In the beginning it was somewhat of a technical challenge, but now it’s another method that our artisans have mastered.

Vikram Goyal Studio at PAD Design + Art. Nilufar Gallery.

Shaded Graphite Cupboard. Brass and Black Porter Stone, Hollowed Joinery. 96" L x 24" D x 38" H.

Image courtesy of Vikram Goyal.

Vikram Goyal Studio at PAD Design + Art. Nilufar Gallery.

Shaded Graphite Cupboard (detail). Brass and Black Porter Stone, Hollowed Joinery. 96" L x 24" D x 38" H.

Image courtesy of Vikram Goyal.

Artisans at work at Vikram Goyal Studio in New Delhi.

Courtesy of Vikram Goyal.

Artisans at work at Vikram Goyal Studio in New Delhi.

Courtesy of Vikram Goyal.

Vikram Goyal Studio at PAD Design + Art. Nilufar Gallery.

Flow Table C. Brass and Black Porter Stone, Repousse and Hollowed Joinery. 35" L x 28" W x 17" H.

Image courtesy of Vikram Goyal.

Your work often reinterprets historical motifs and narratives in fresh, modern ways. Could you tell us about a particular piece where you felt this fusion was most successful?

We created a large repoussé mural in brass, consisting of 12 panels, inspired by Jaipur’s Jantar Mantar [ an astronomical observation site built in the early 18th century ]. This had 12 architectural instruments, each one representing a different sun sign. These instruments were first used to measure and calculate astronomical elements and influenced the imagery of the piece we created.The final work was imposing [ measuring 8.5 by 2.5 metres ] with intricate detail. It was actually the intricate beauty that inspired the editor of Architectural Digest India to create a cover [ for the magazine’s July-August 2024 Craftsmanship issue ] that depicted a microcosm of the piece and was similarly contoured [ the result of an emboss-deboss paper innovation technique ]—it was a wonderful homage to our work.

You recently launched Viya. How does it differ from your Studio work?

The Studio, whose latest work will showcase at PAD London (October 8 - 13, 2024), focuses on limited edition, collectible design pieces. With Viya, I wanted to expand into multiple crafts associated with India, to create a more diverse product range. What’s important is that every product is artisanal and deeply rooted in culture, from fables and storytelling to the landscape and textiles - making contemporary Indian style accessible to the rest of the world.

Vikram Goyal & Nina Yashar.

Photography by Stephane Aboudaram, @wearecontents.

Vikram Goyal Studio at PAD Design + Art. Nilufar Gallery.

Shaded Graphite Cabinet (detail). Brass, Hollowed Joinery. 48" W x 22" D x 72" H.

Image courtesy of Vikram Goyal.