Refugee Stories Come to Life in "UNPACKED: Refugee Baggage"

Words by Eric David

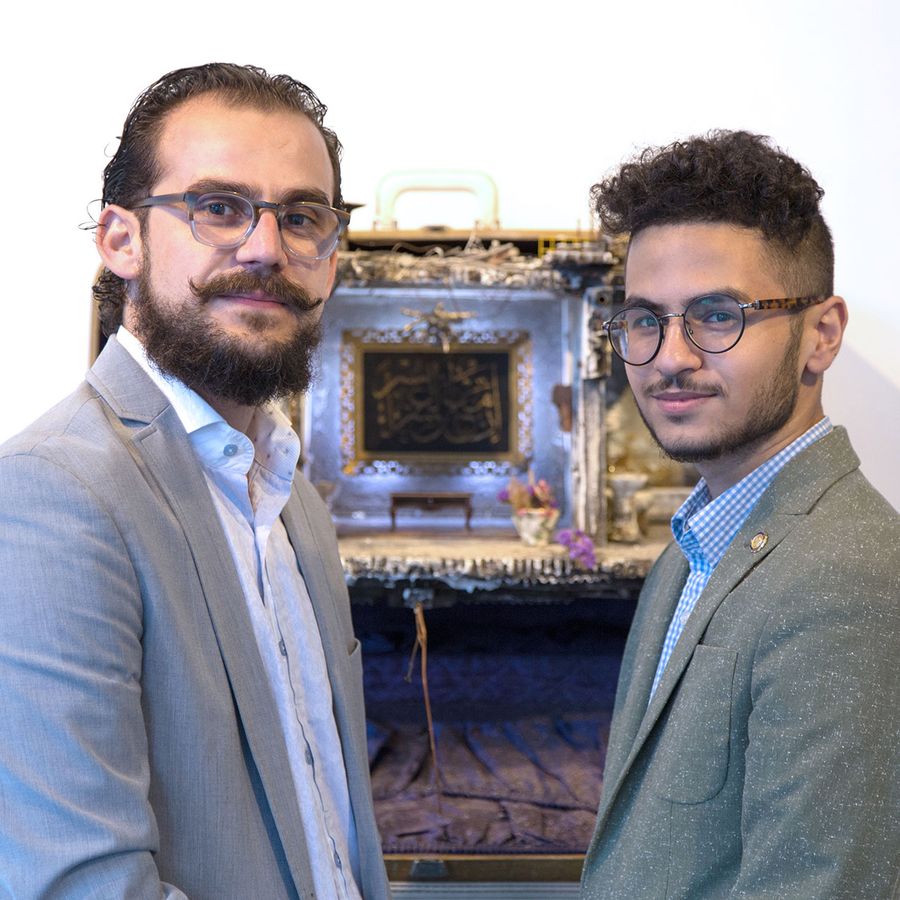

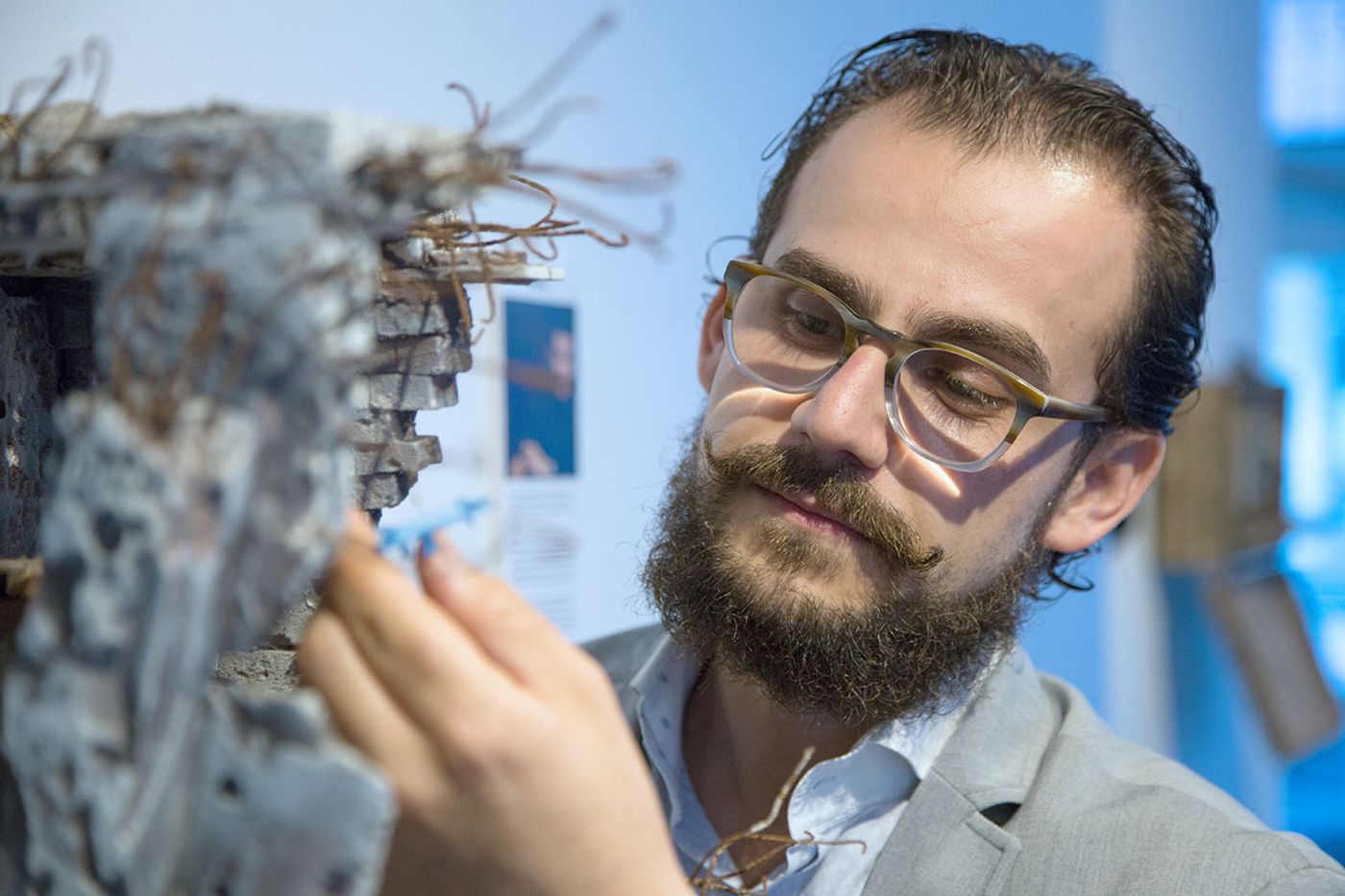

Location

Refugees forcibly fleeing war-torn countries have featured prominently on the news for quite a few years now, but although we have all certainly heard about their plight in terms of numbers and geography, their emotional and psychological experience remains unknown for anyone not in their shoes. “UNPACKED: Refugee Baggage”, a multi-media installation by Syrian-born, New Haven-based artist and architect Mohamad Hafez and Iraqi-born writer and speaker Ahmed Badr, attempts to rectify this glaring gap by shedding light on the personal stories that have been overshadowed by the generic label of “refugee”.

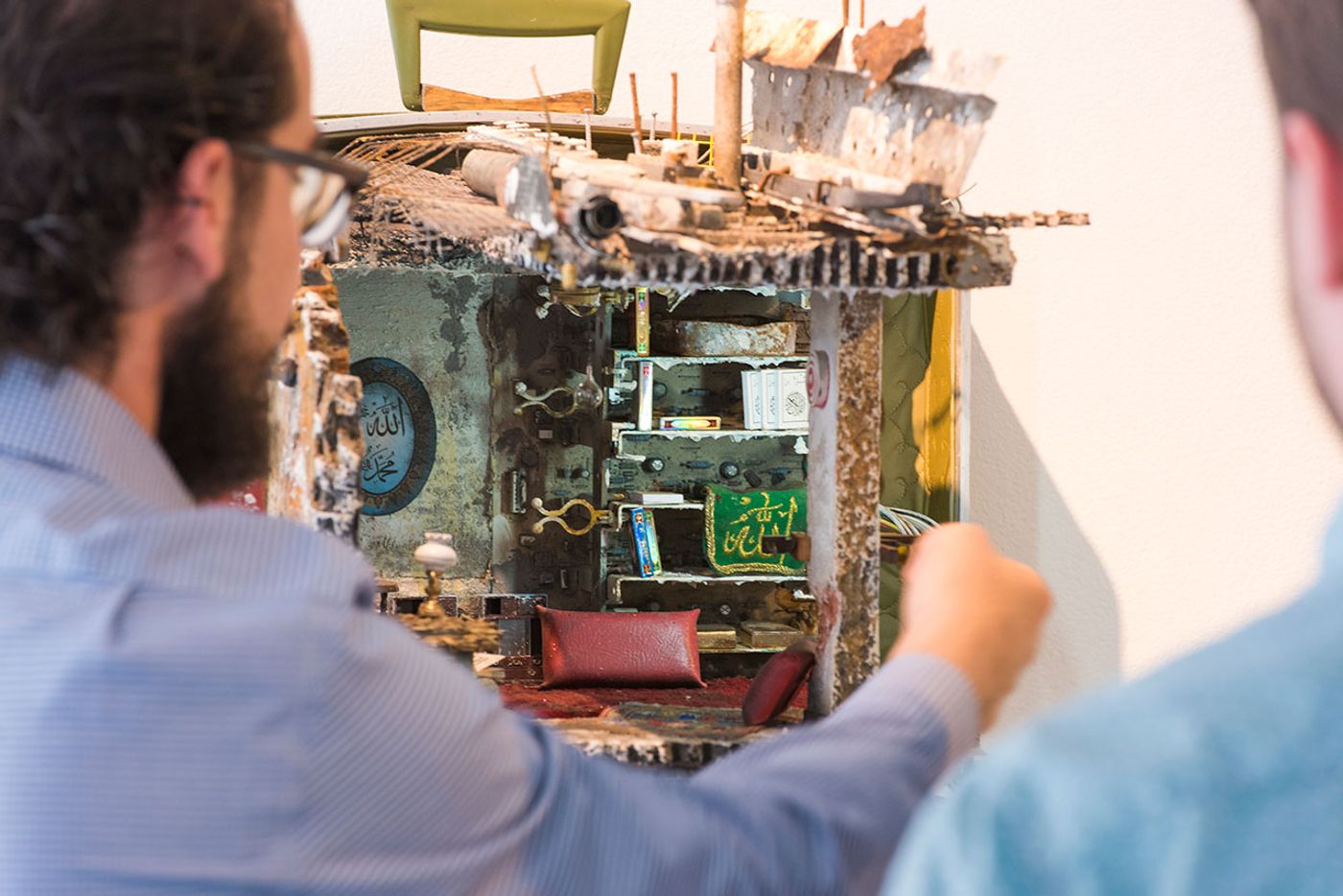

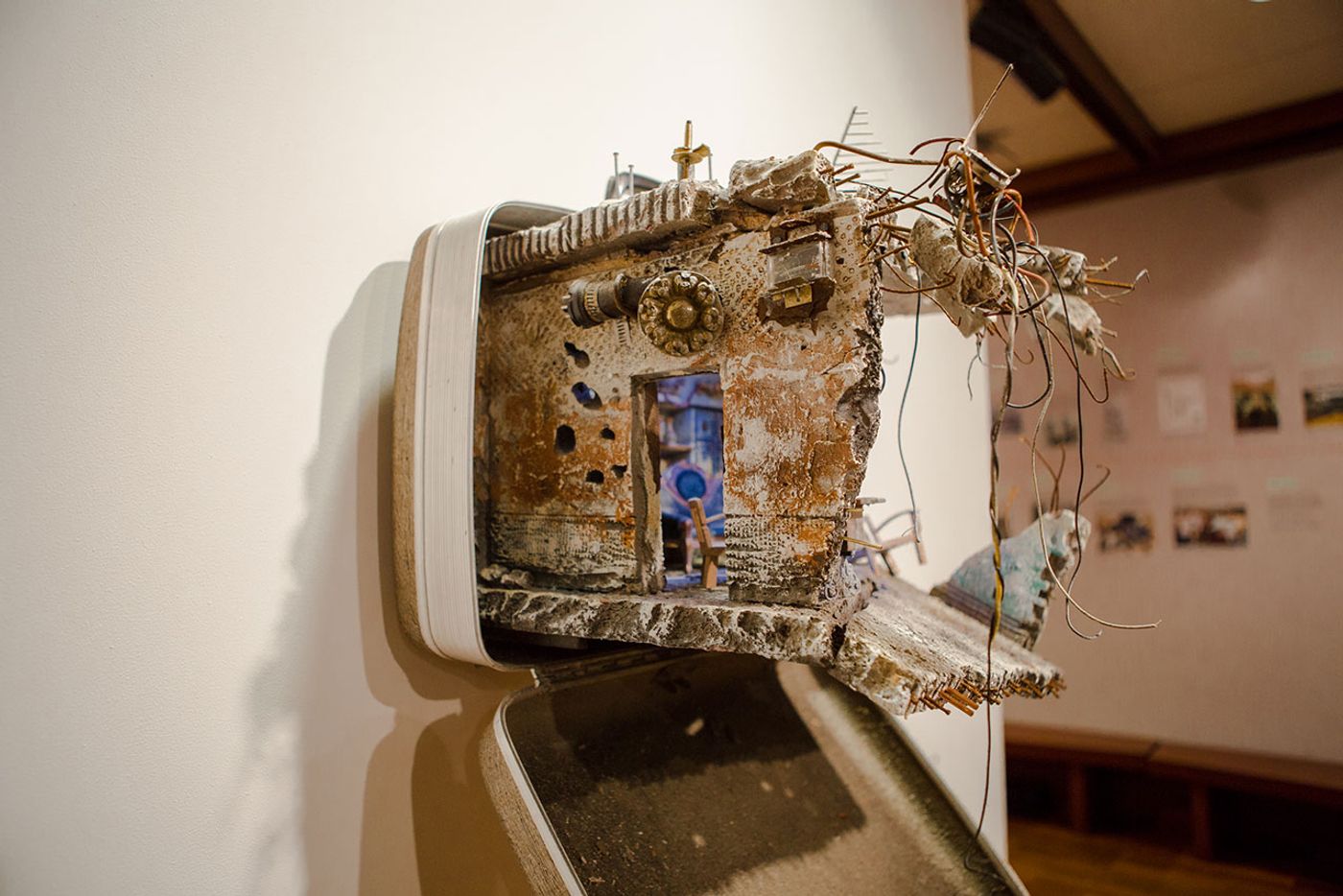

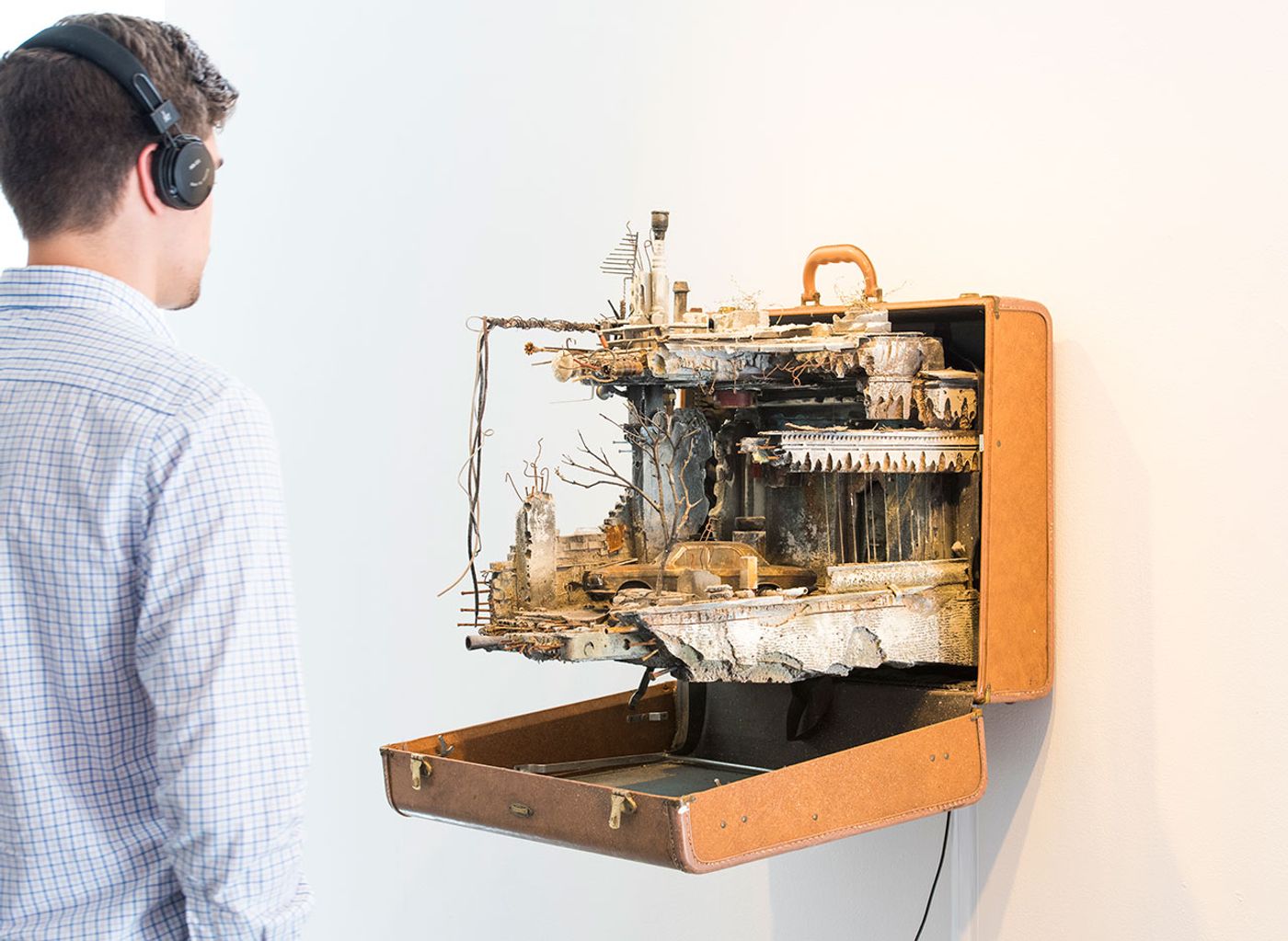

In order to humanize this label and expand its definition, Hafez and Badr focused on individual stories from families from Afghanistan, Congo, Syria, Iraq and Sudan, who have resettled in America. Collected and curated by Badr, their stories have been painstakingly transformed by Hafez into dioramas that portray as accurately as possible the homes they left behind. The three-dimensional replicas are fittingly set inside suitcases, a lyrical reminder of the long and perilous journeys that refugees unwillingly embark on, and the physical and emotional baggage they carry henceforth.

Initially exhibited in 2017 at Art Space in Hafez’s hometown of New Haven, the installation, which has since been travelling around the US and is now on view at Iowa State University until October 19, 2018, showcases each scale model along with a pair of headsets that allow visitors to listen to the stories in the refugees’ own voices.

Mohamad Hafez and Ahmed Badr portrait. Photo by David Ritter.

UM SHAHAM: War and a Burnt Car. Photo by Rodney Nelson.

Photo by Rodney Nelson.

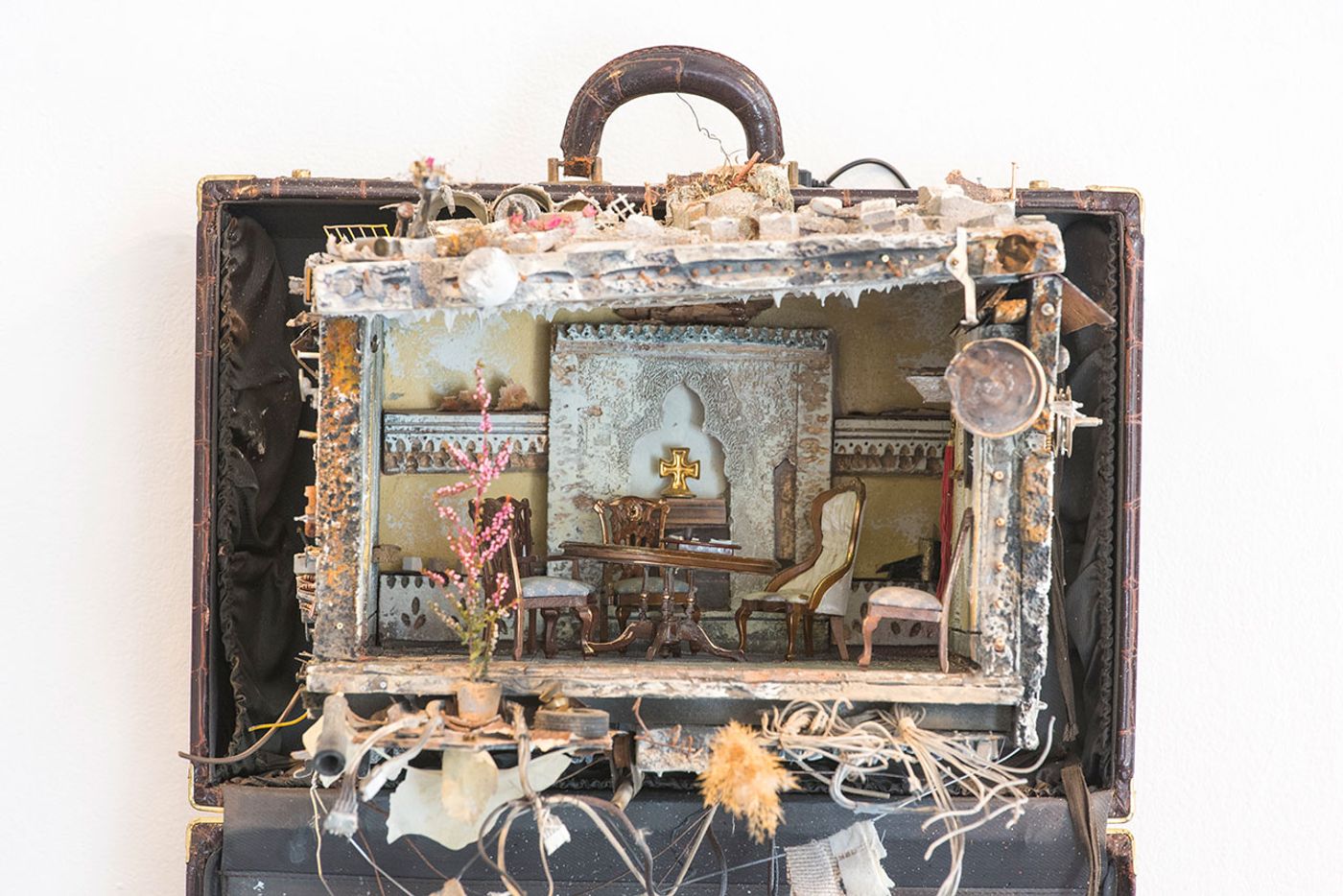

MOHAMAD: A Regal Living Room. Photo by Rodney Nelson.

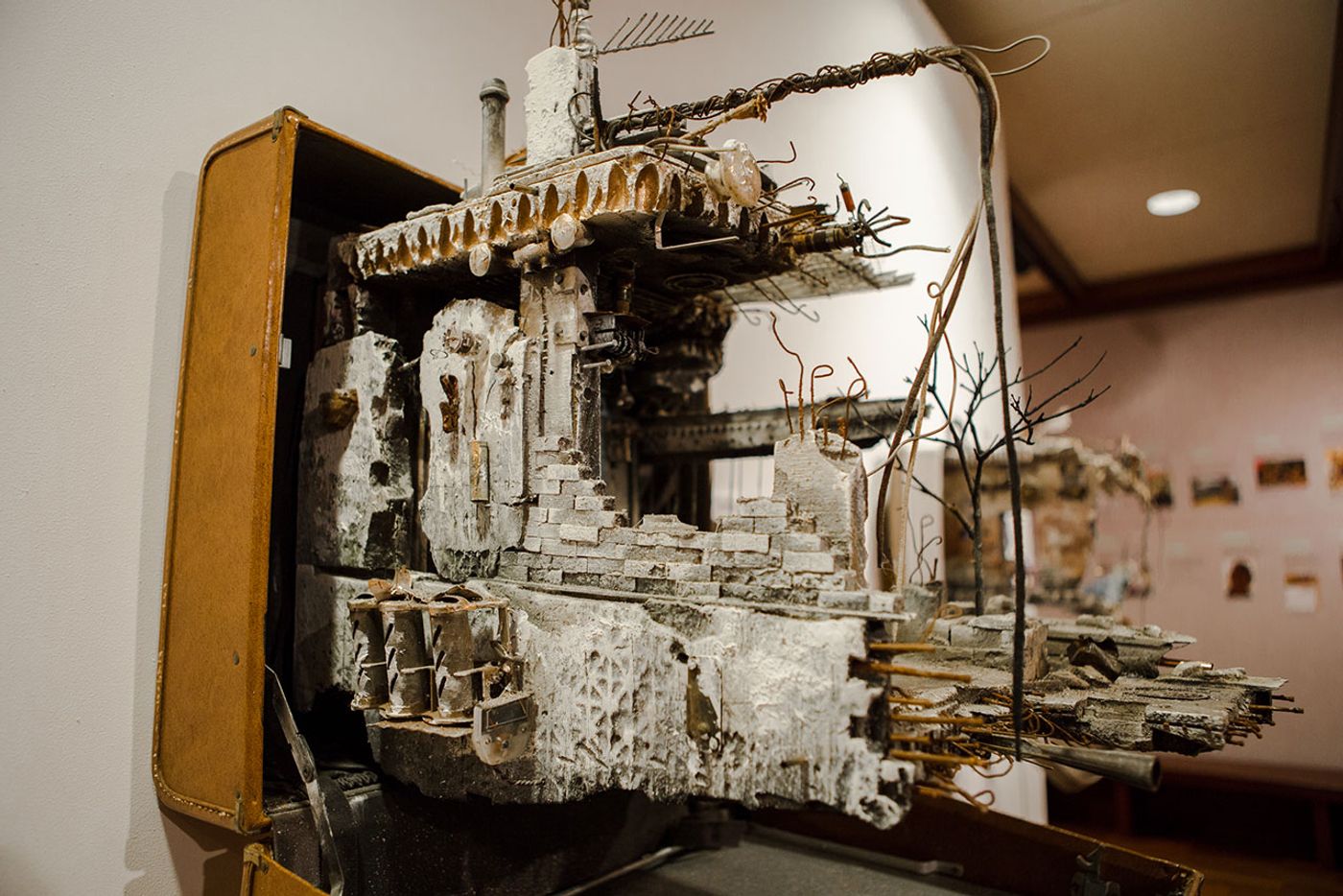

BADR FAMILY: A Bombed Home. Photo by Rodney Nelson.

Built in great detail over a period of months, each miniature diorama bears the particular scars that each refugee family experienced, bringing to life the personal dimension of each tragic tale, and “inviting the spectator”, as Badr says, “to simultaneously experience horror, pain, and awe”. The abandoned, gutted living rooms, bedrooms, and kitchens both convey the ravages of conflict and war the families were running away from, and poignantly allude to the resilience that they had to muster to do so. But more than that, as Hafez explains, they convey that "the refugees are normal human beings, with families and dreams and aspirations, just like any American”.

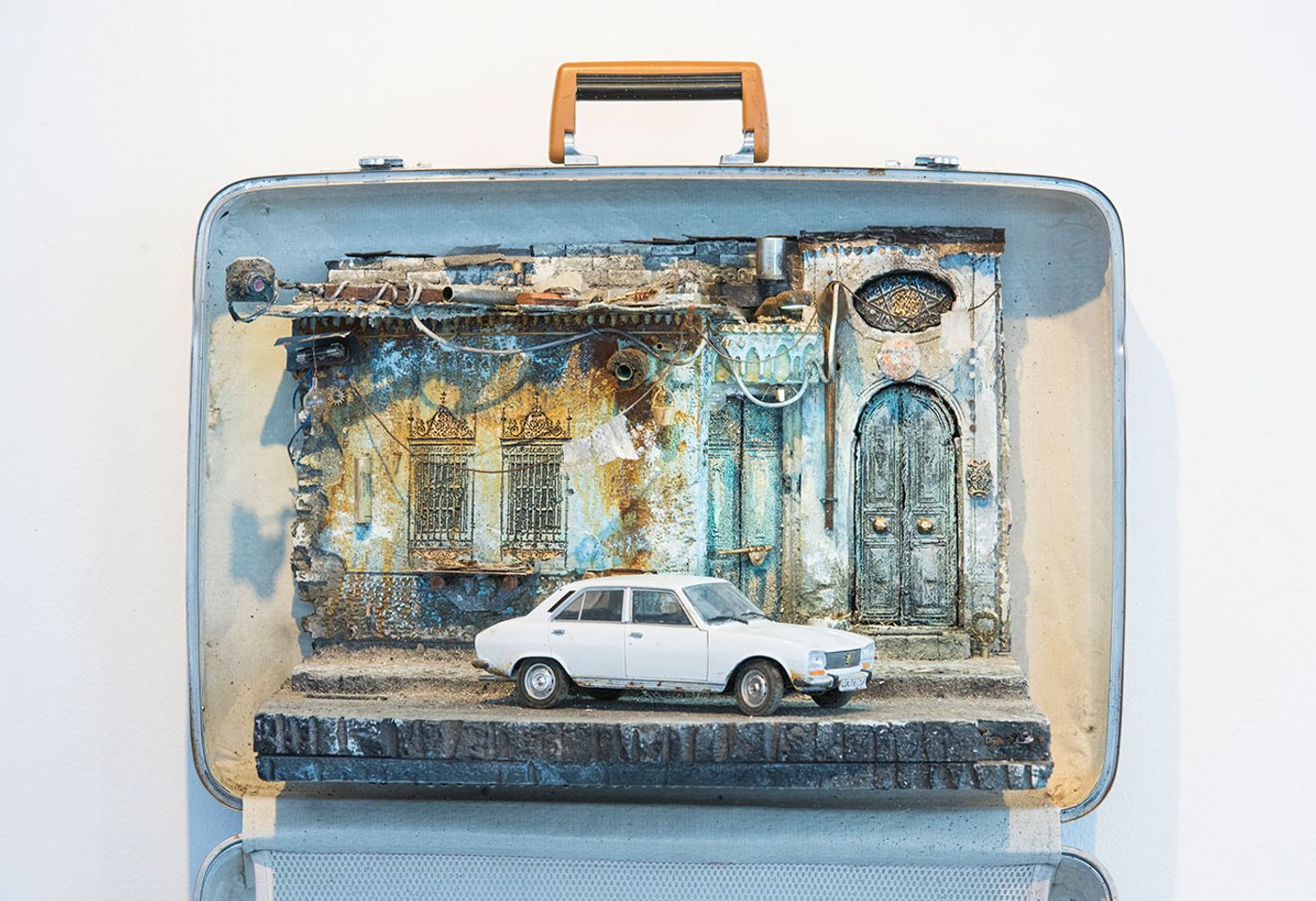

Each story is harrowing in its own distinct way reflecting both the narrators’ personal experiences and the specific circumstances that forced them to flee. Prominent in Amjad’s story for example is a white Peugeot 504, the Syrian Secret Police’s vehicle of choice. The car is a symbol of the oppression and brutality as well as an indelible part of Amjad’s memories—as it is the same car in which Amjad’s neighbour, a fellow activist, was arrested in. Informed that his name was placed on government watch lists, a sign that his freedom was in jeopardy, Amjad fled Syria in 2013 and later resettled in New Haven where he now works as an architect.

AZHAAR & FOUAD: A Father's Pride. Photo by Rodney Nelson.

AMJAD: A White Car. Photo by Rodney Nelson.

AMJAD: A White Car. Photo by Rodney Nelson.

Photo by Rodney Nelson.

JOSEPH: A Missing Son. Photo by Rodney Nelson.

UM SHAHAM: War and a Burnt Car. Photo by Rodney Nelson.

UM SHAHAM: War and a Burnt Car. Photo by Rodney Nelson.

For Um Shaham, a mother of four from Mosul, calamity struck when her house was burnt down leaving her and her son with third and second degree burns. It struck again a few months into the Iraq war, when Um Shaham’s husband was shot dead by a stray bullet while driving his taxi around Mosul. The widowed family was eventually resettled in America after living for two years in Turkey. Listening to her story in front of the replica of the family’s burnt down house imparts Um Shaham’s words with a visceral and painful immediacy but also conveys a sense of relief that they were lucky to escape the inferno.

The installation would not be complete without a suitcase for each of the project's two collaborators—after all, they both are refugees. In Hafez’s diorama, an antique giltwood sofa, a crystal chandelier and baroque wall decorations nostalgically hint at the opulent beauty of his home in Damascus which he has not visited for the past 16 years. Badr’s family home in Baghdad on the other hand presents a grimmer picture. Bombed by militia troops on July 25th, 2006, the maquette shows the eerie aftermath when a missile entered the house through the bathroom window, pushed through the kitchen walls and penetrated three natural gas canisters. Luckily the canisters were emptied a few days before and all family members survived. A week after the bombing Badr, his parents and sister relocated to Syria and after two years were resettled in America.

At a time when xenophobic forces are gaining ground around the world and when so many refugees are turned away by nationalistic governments, it is imperative that stories that give voice to the voiceless like these are told.

JOSEPH: A Missing Son. Photo by Rodney Nelson.

FERESHTEH: A Secret School (detail). Photo by Rodney Nelson.

AYMAN & GHENA: A Coffee Cup. Photo by Rodney Nelson.

FERESHTEH: A Secret School (detail). Photo by Rodney Nelson.

AYMAN & GHENA: A Coffee Cup. Photo by Rodney Nelson.

Photo by David Ritter.

I've always believed that artists are the documentaries of their times.—Mohamad Hafez

Photo by Rodney Nelson.

Photo by Rodney Nelson.

UM SHAHAM: War and a Burnt Car. Photo by Rodney Nelson.

AMJAD: A White Car. Photo by Rodney Nelson.

AYMAN & GHENA: A Coffee Cup. Photo by Anisha Sisodia.

AYMAN & GHENA: A Coffee Cup. Photo by Anisha Sisodia.

UM SHAHAM: War and a Burnt Car. Photo by Anisha Sisodia.

UM SHAHAM: War and a Burnt Car. Photo by Anisha Sisodia.

UM SHAHAM: War and a Burnt Car. Photo by Anisha Sisodia.

Photo by Anisha Sisodia.

Photo by Anisha Sisodia.

Photo by Anisha Sisodia.

MOHAMAD: A Regal Living Room. Photo by Rodney Nelson

MOHAMAD: A Regal Living Room. Photo by Rodney Nelson