The Algorithmic Beauty of Dimitris Ladopoulos' Portraits

Words by Eric David

Location

Art and technology has always had a contentious relationship, from the invention of the photographic camera, to video recorders, to computers, artists have both passionately appropriated and decried technological advancements. For Greek visual designer and art director Dimitris Ladopoulos, who has always been inspired by both the arts and technology, their confluence only holds great potential, exemplified by his recent project “Portraits” where a bespoke algorithm re-interprets classical oil paintings though a contemporary, technological lens.

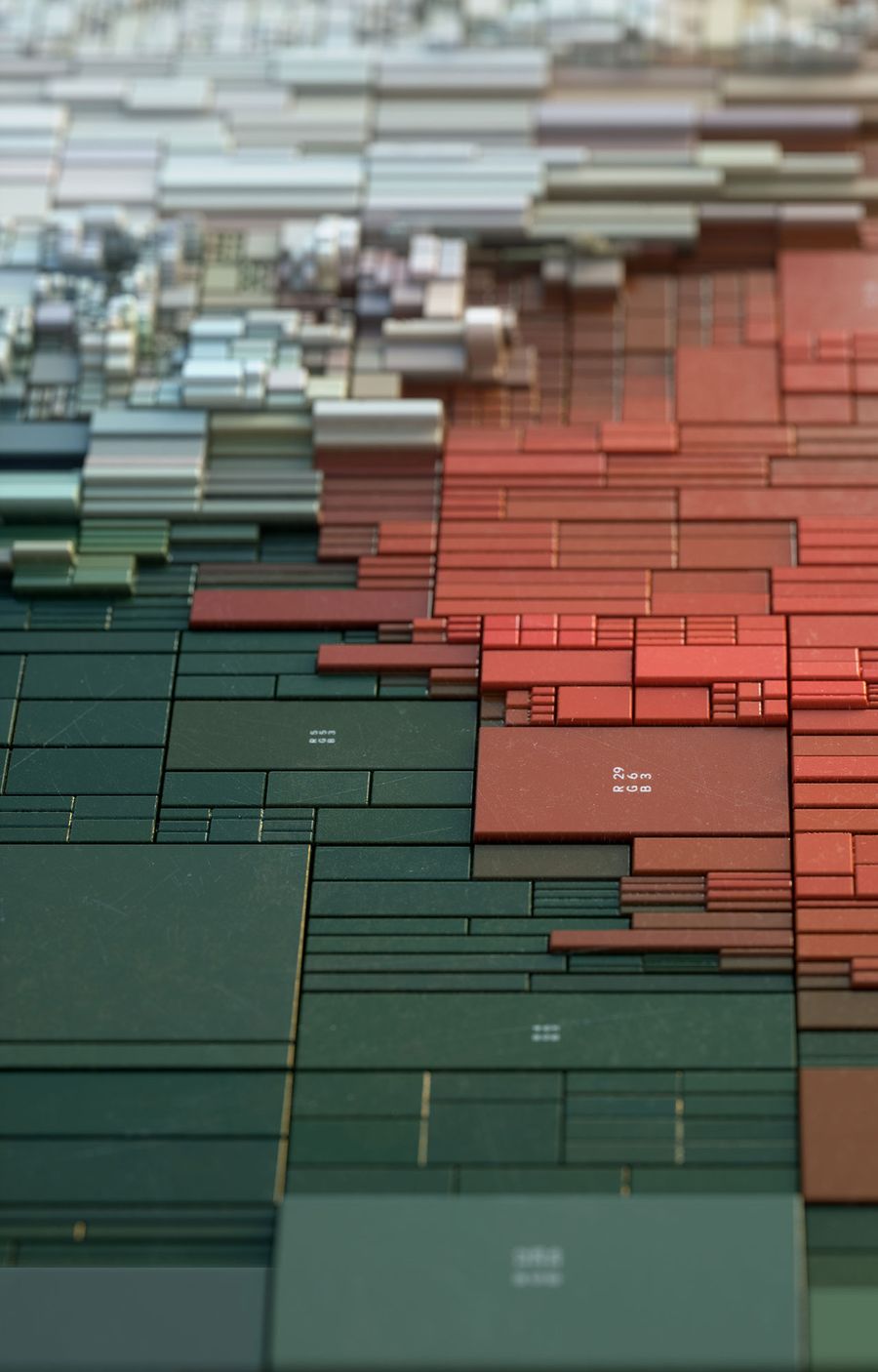

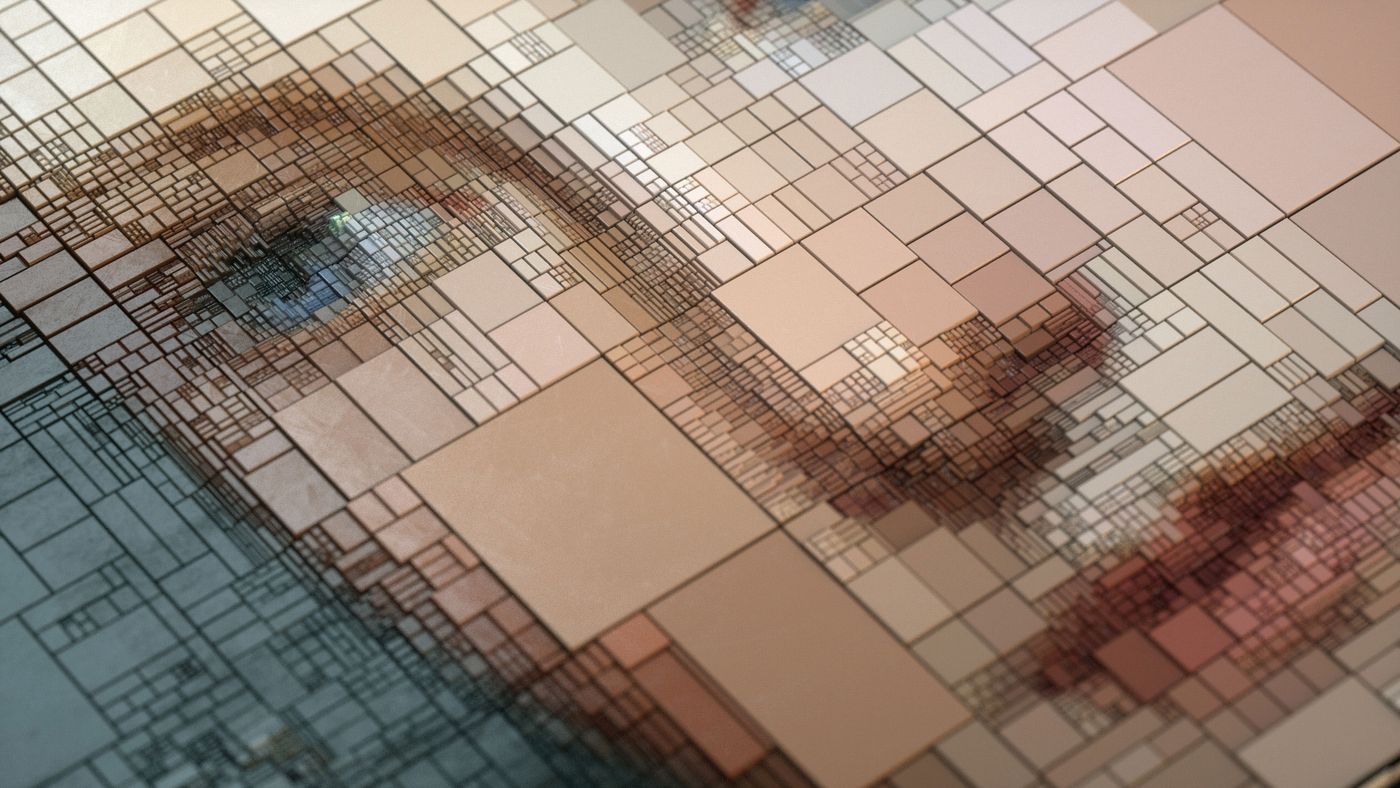

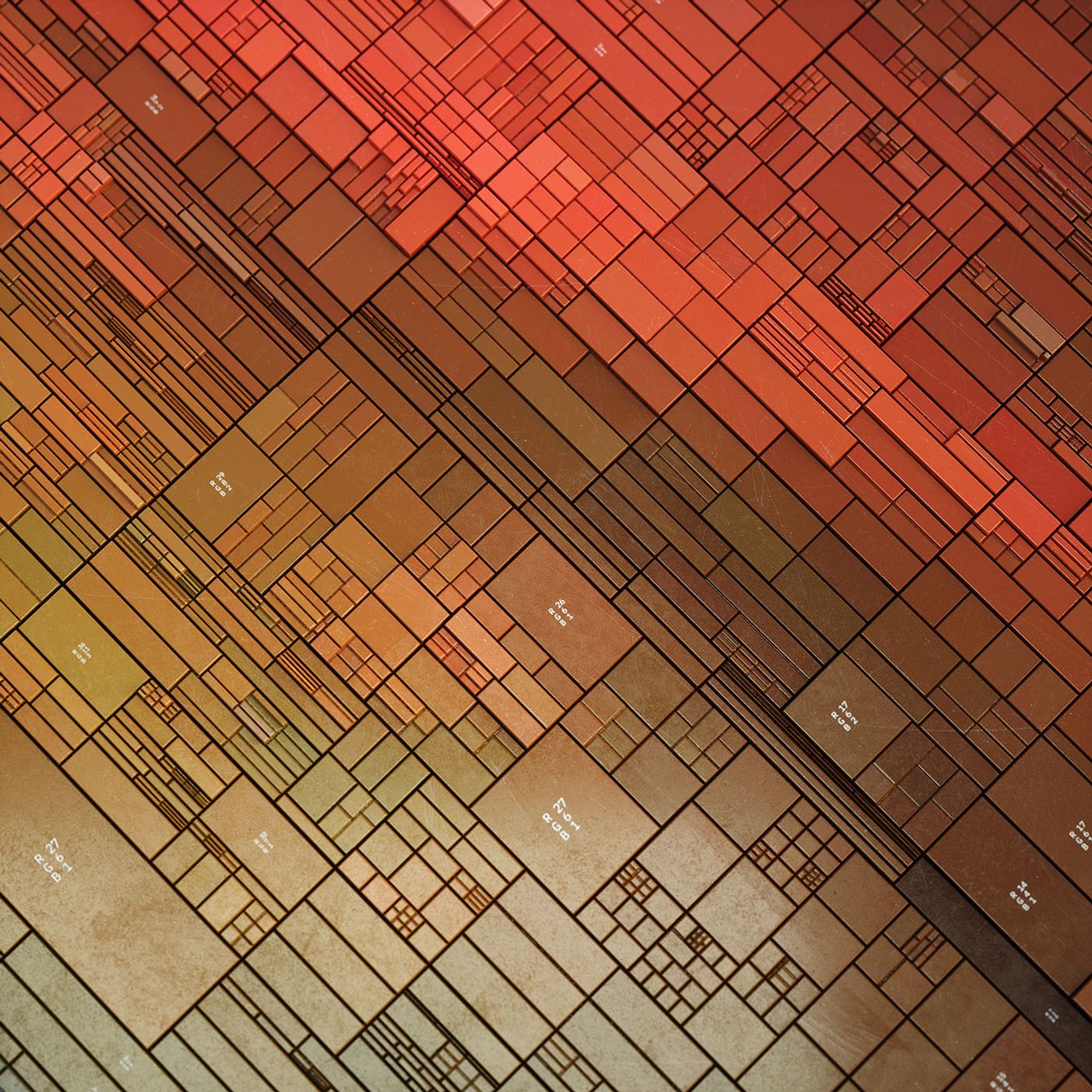

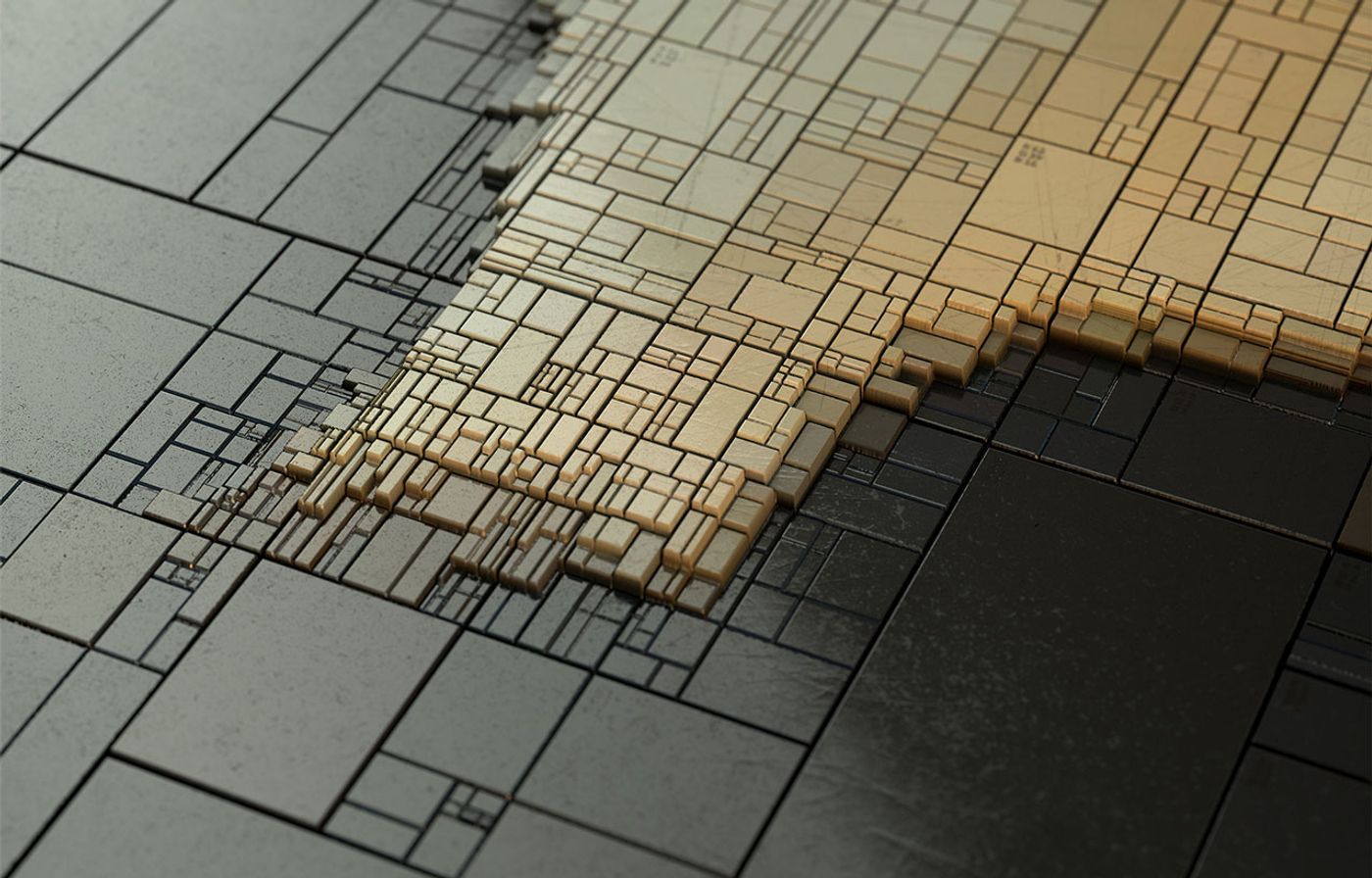

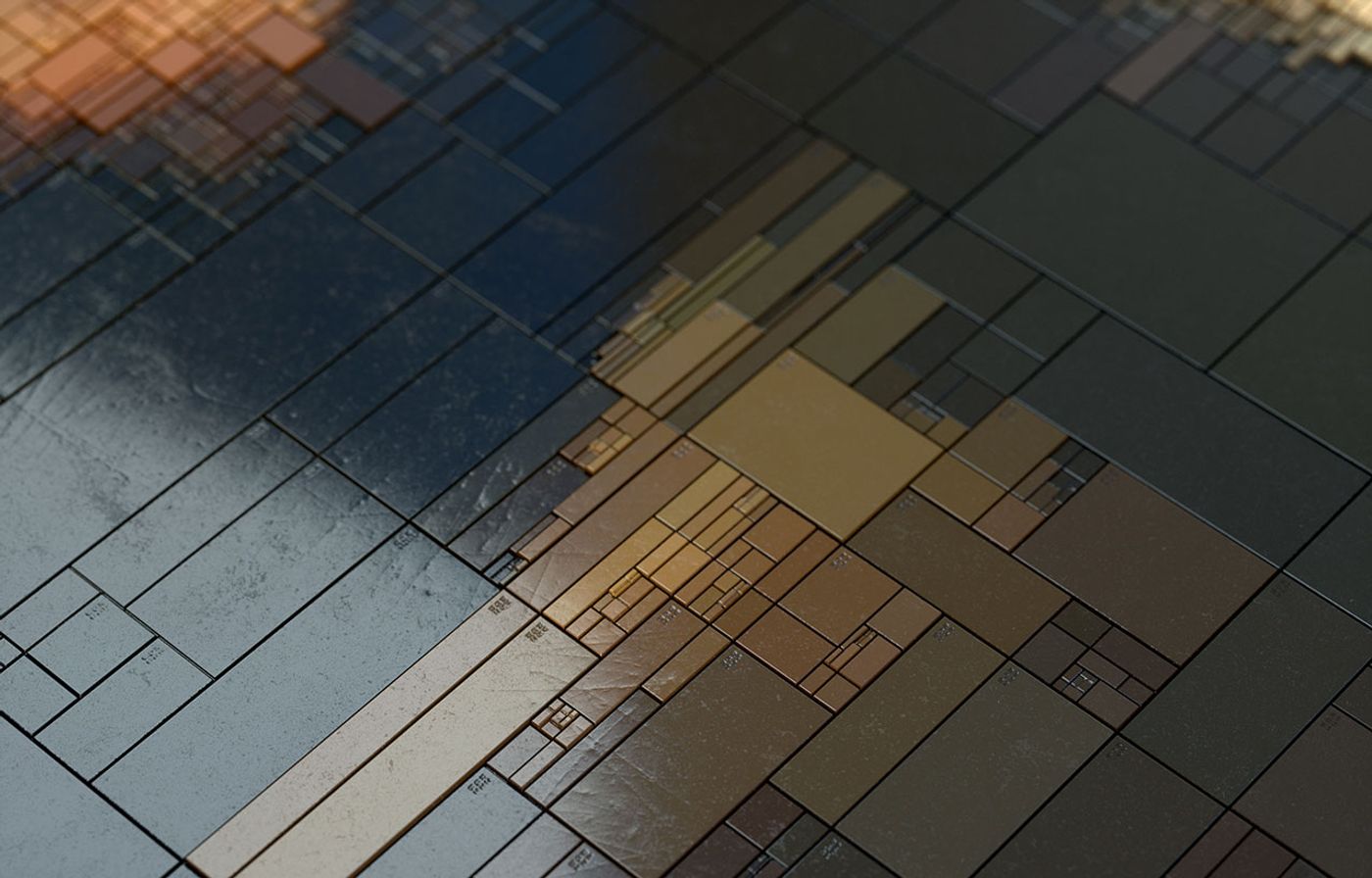

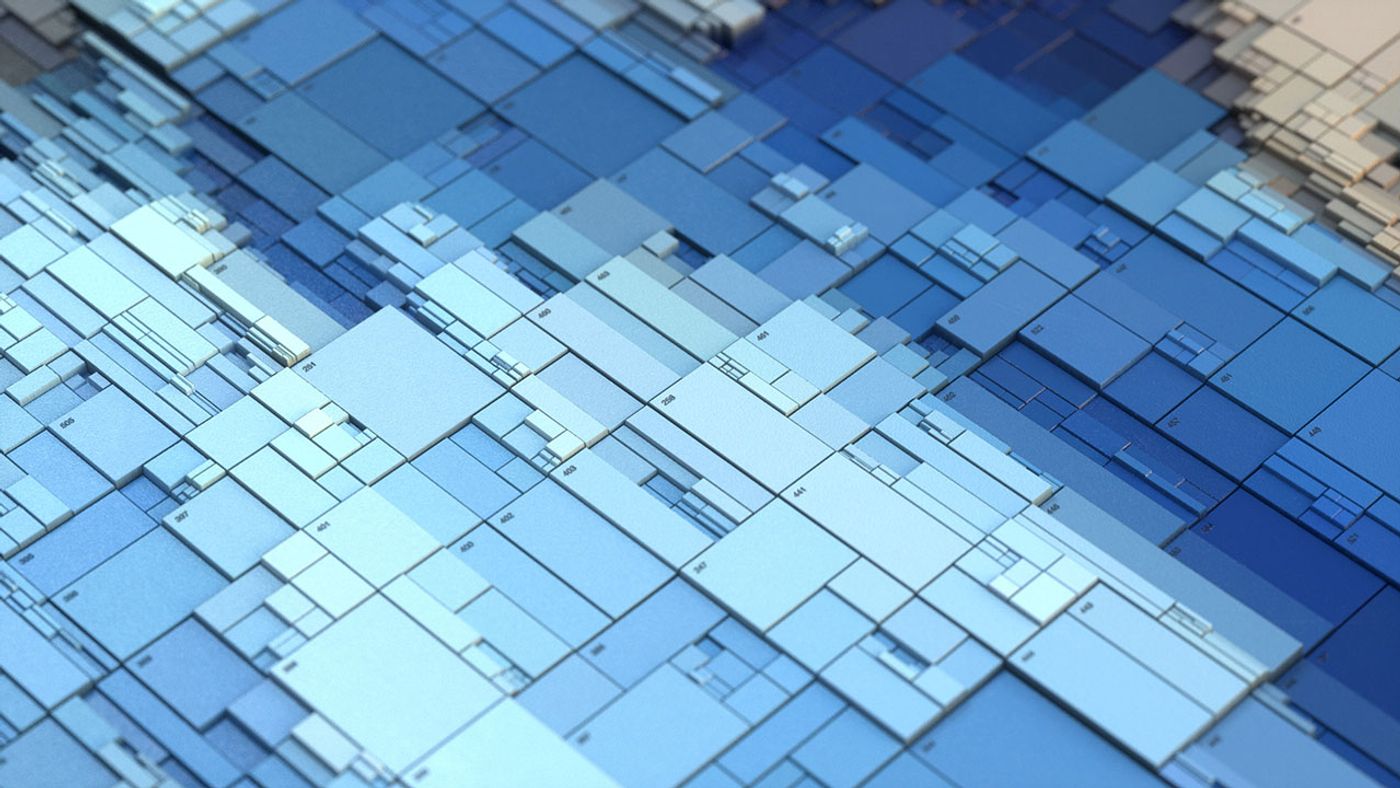

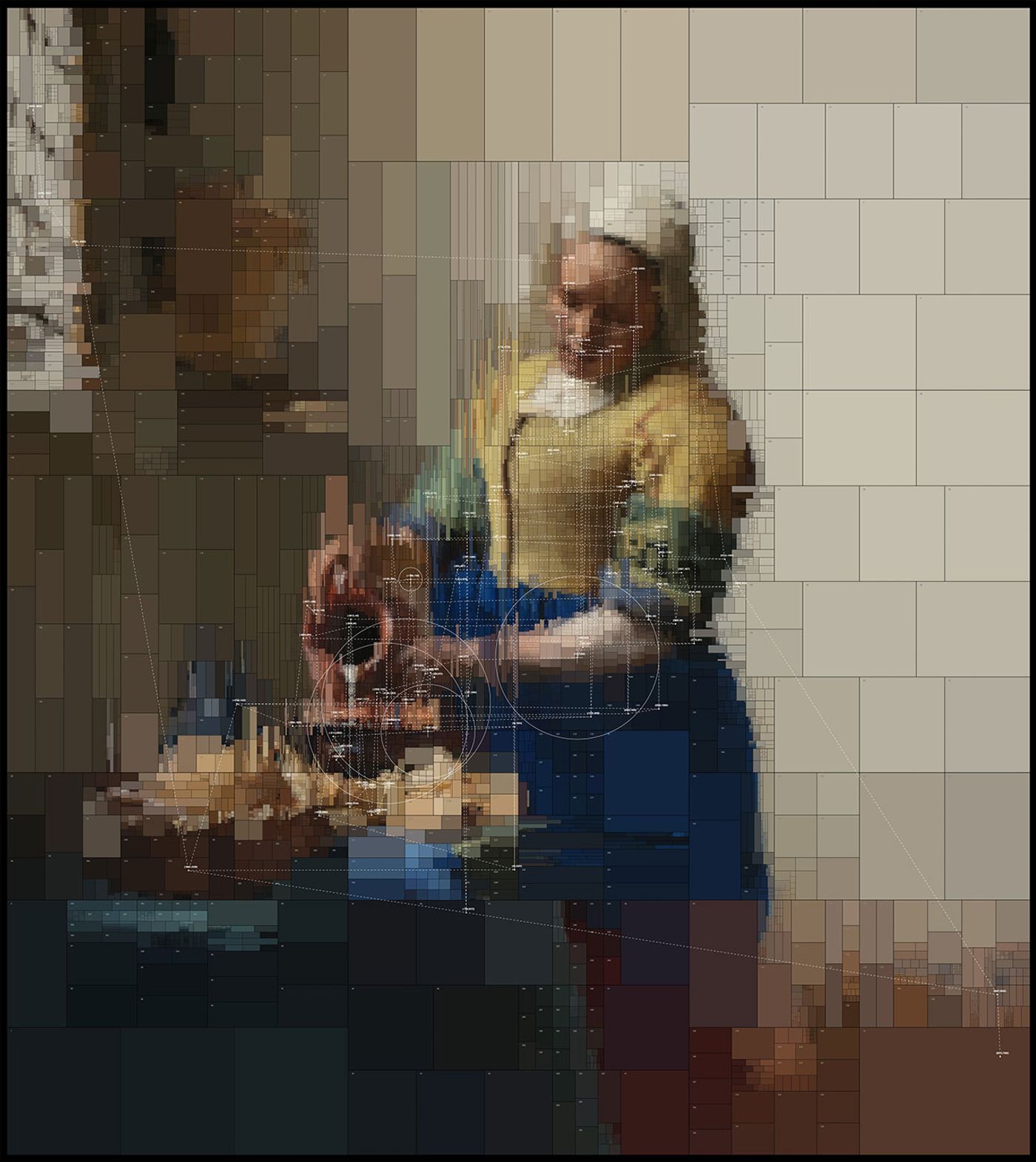

The project stems from Ladopoulos’ fascination with “treemapping”, an information visualisation method for displaying hierarchical data using nested rectangles, and involved the creation of an algorithm in Houdini, a 3D animation application software. The experimental algorithm, which took four days to initially develop and which is being continuously revised and fine-tuned, calculates the density of the information of a given image, and then, based on a few user-controllable parameters, subdivides it into a kaleidoscopic array of monochromatic rectangles of varying sizes—the less information, the larger the rectangle area, “similar to the painters’ approach of using broader and finer strokes” as Ladopoulos describes it. The result is a geometrical mosaic of colour blocks that hovers between the impressionism of Pointillism and the starkness of computer pixelation.

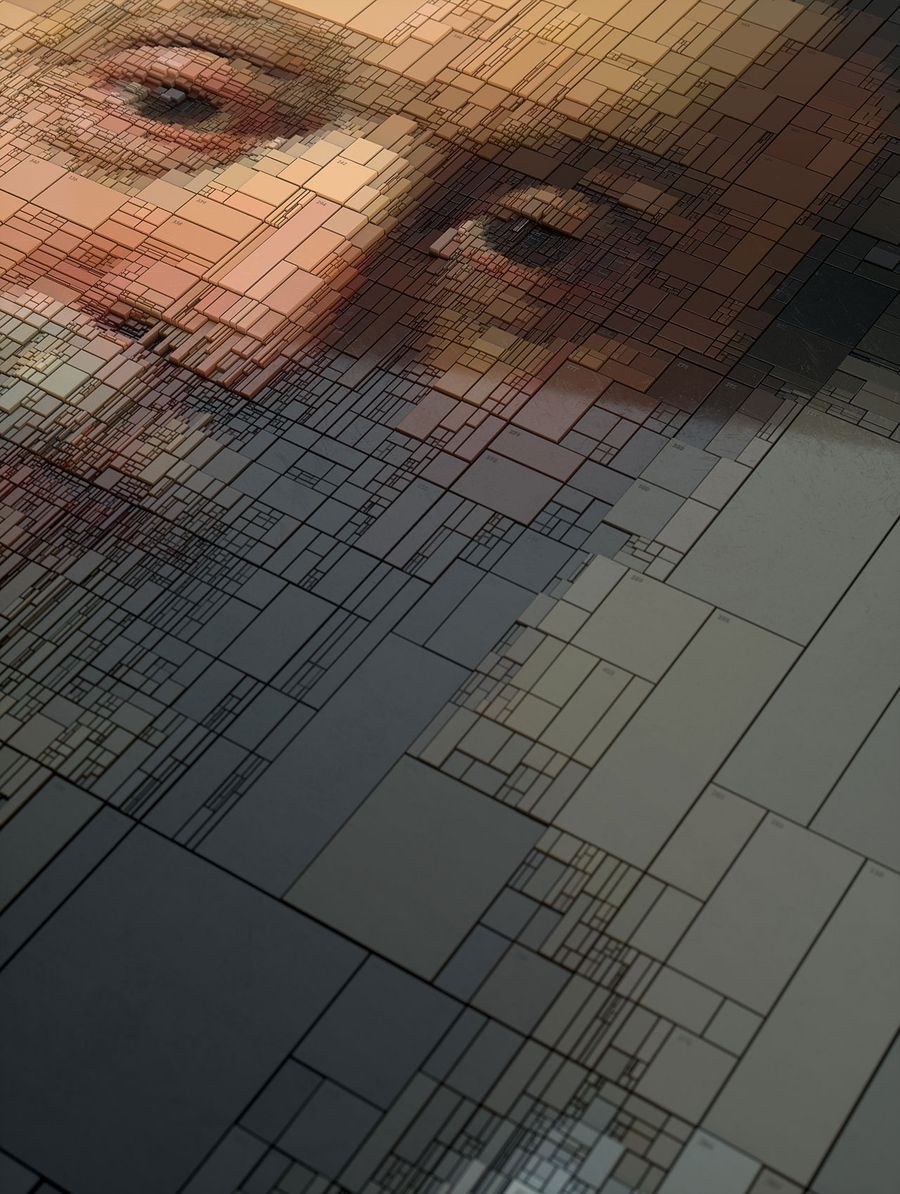

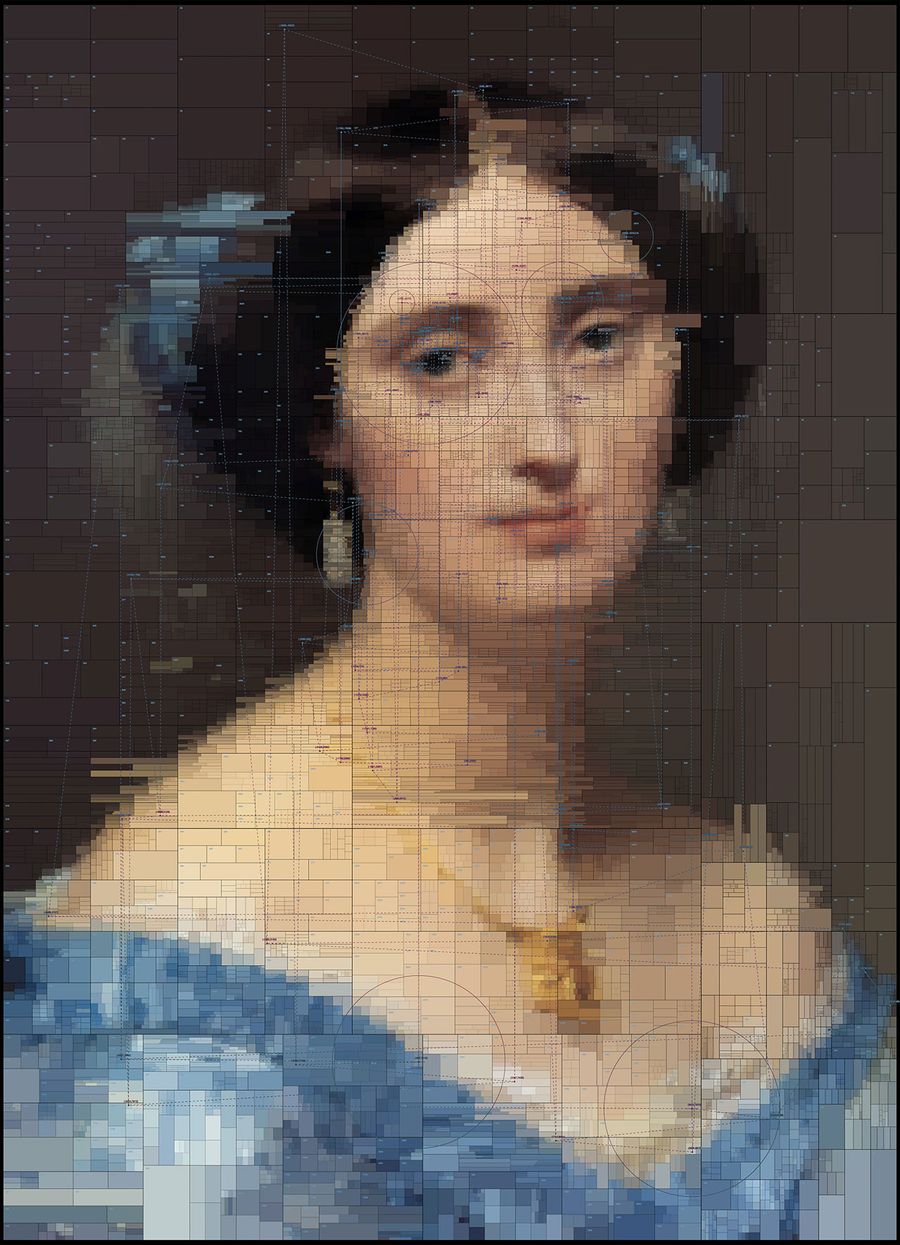

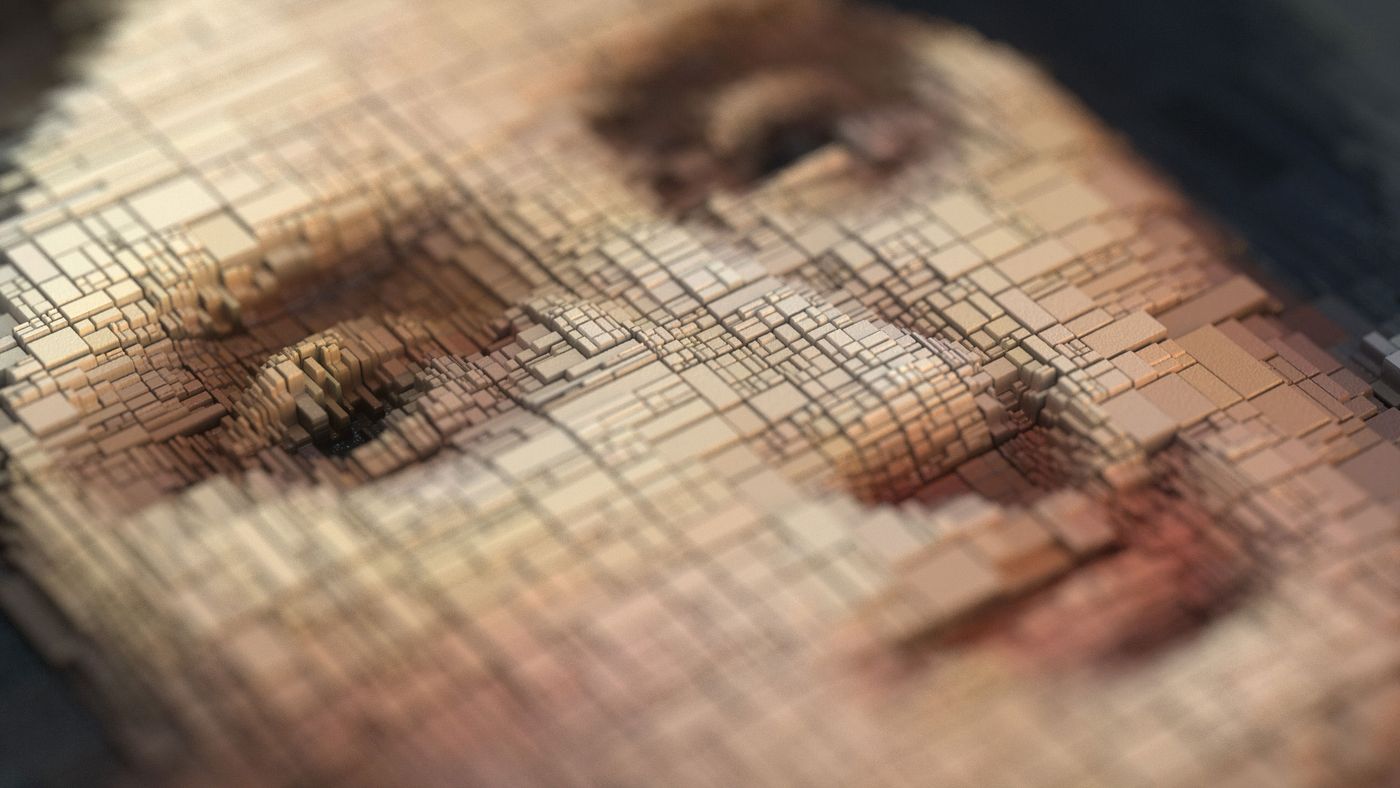

Rosalba (detail), from Portraits series by Dimitris Ladopoulos (Original painting - Portrait of Rosalba Peale by Rembrandt Peale, 1820).

Rosalba, from Portraits series by Dimitris Ladopoulos (Original painting - Portrait of Rosalba Peale by Rembrandt Peale, 1820).

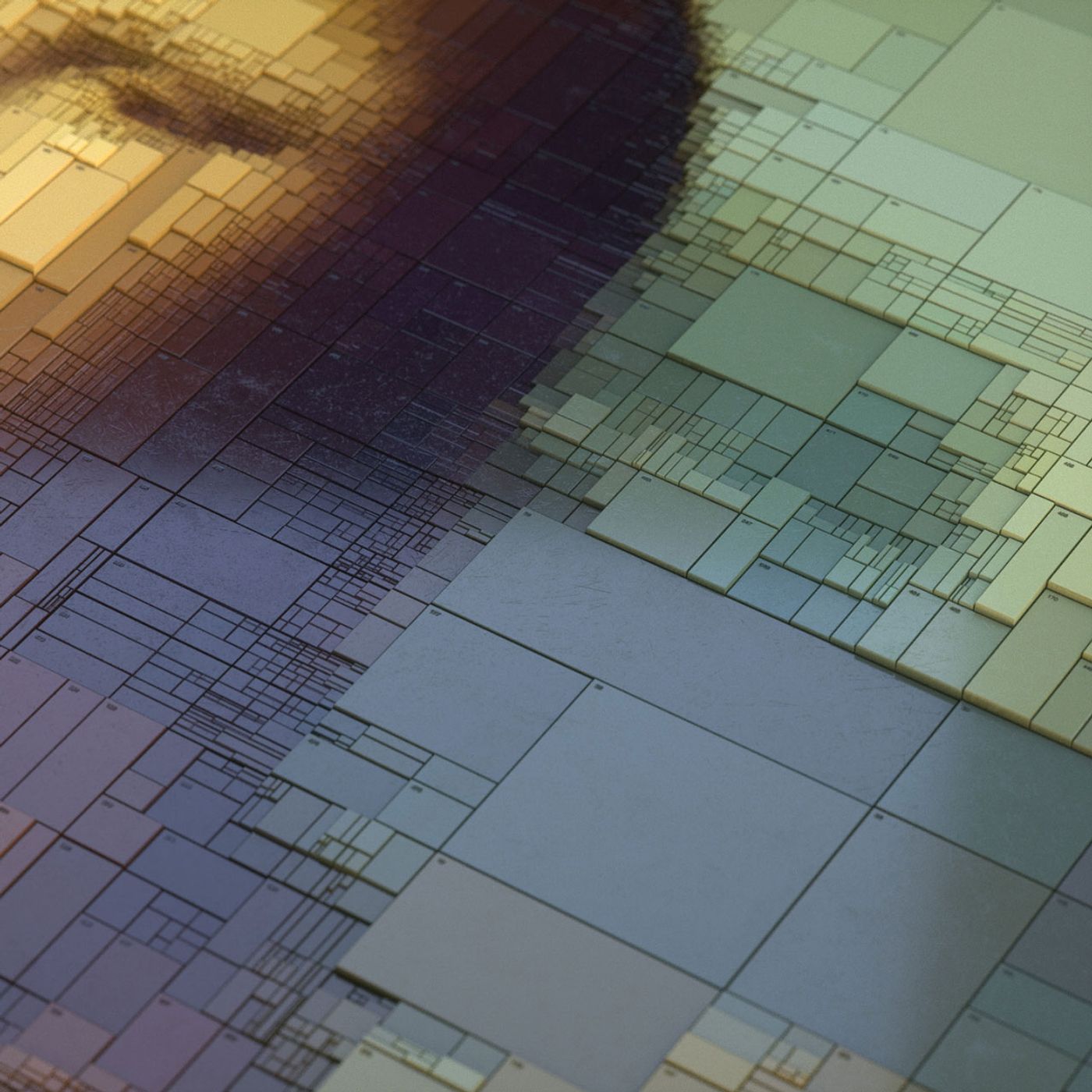

Rosalba (detail), from Portraits series by Dimitris Ladopoulos (Original painting - Portrait of Rosalba Peale by Rembrandt Peale, 1820).

Rosalba (detail), from Portraits series by Dimitris Ladopoulos (Original painting - Portrait of Rosalba Peale by Rembrandt Peale, 1820).

Rosalba (detail), from Portraits series by Dimitris Ladopoulos (Original painting - Portrait of Rosalba Peale by Rembrandt Peale, 1820).

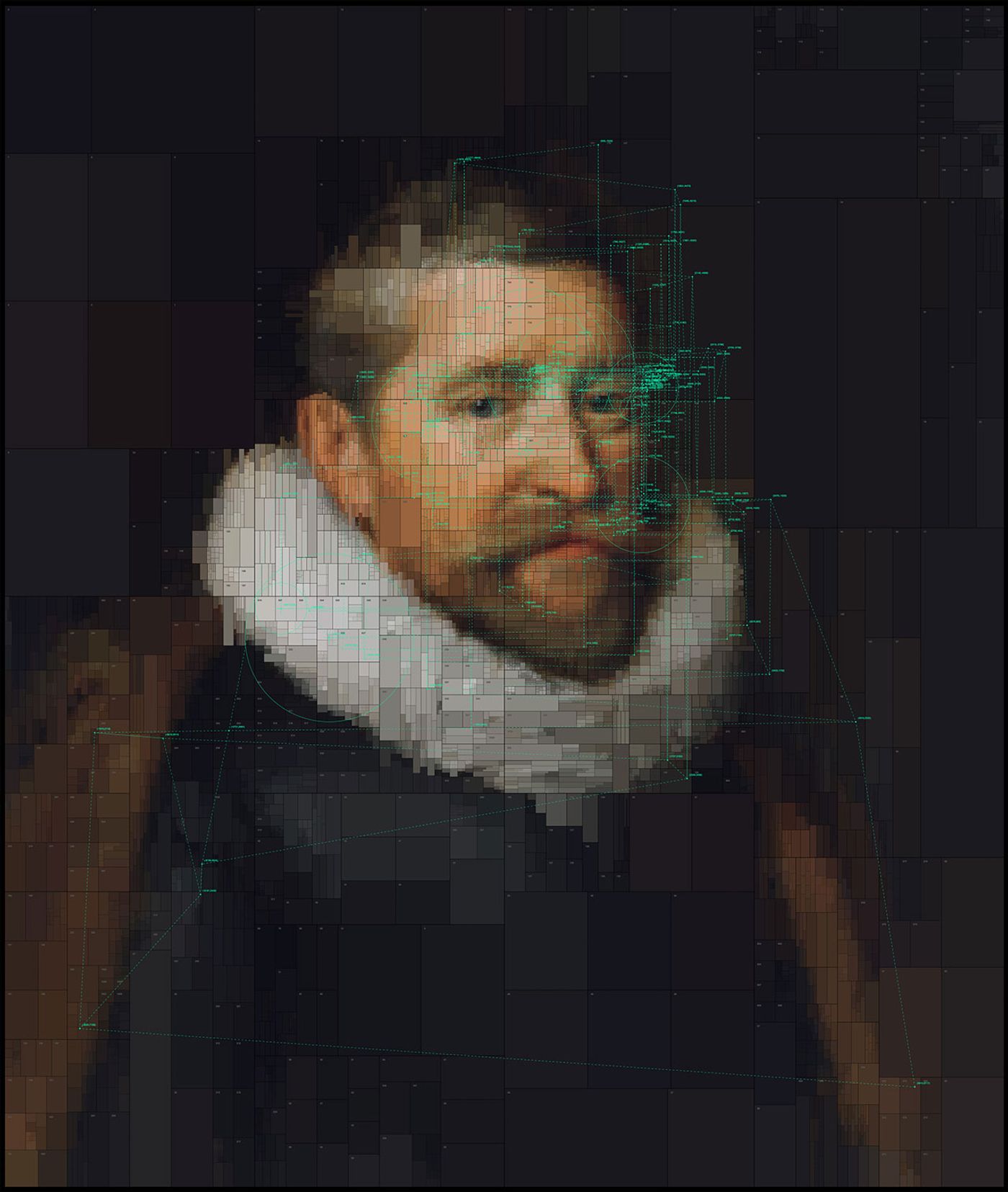

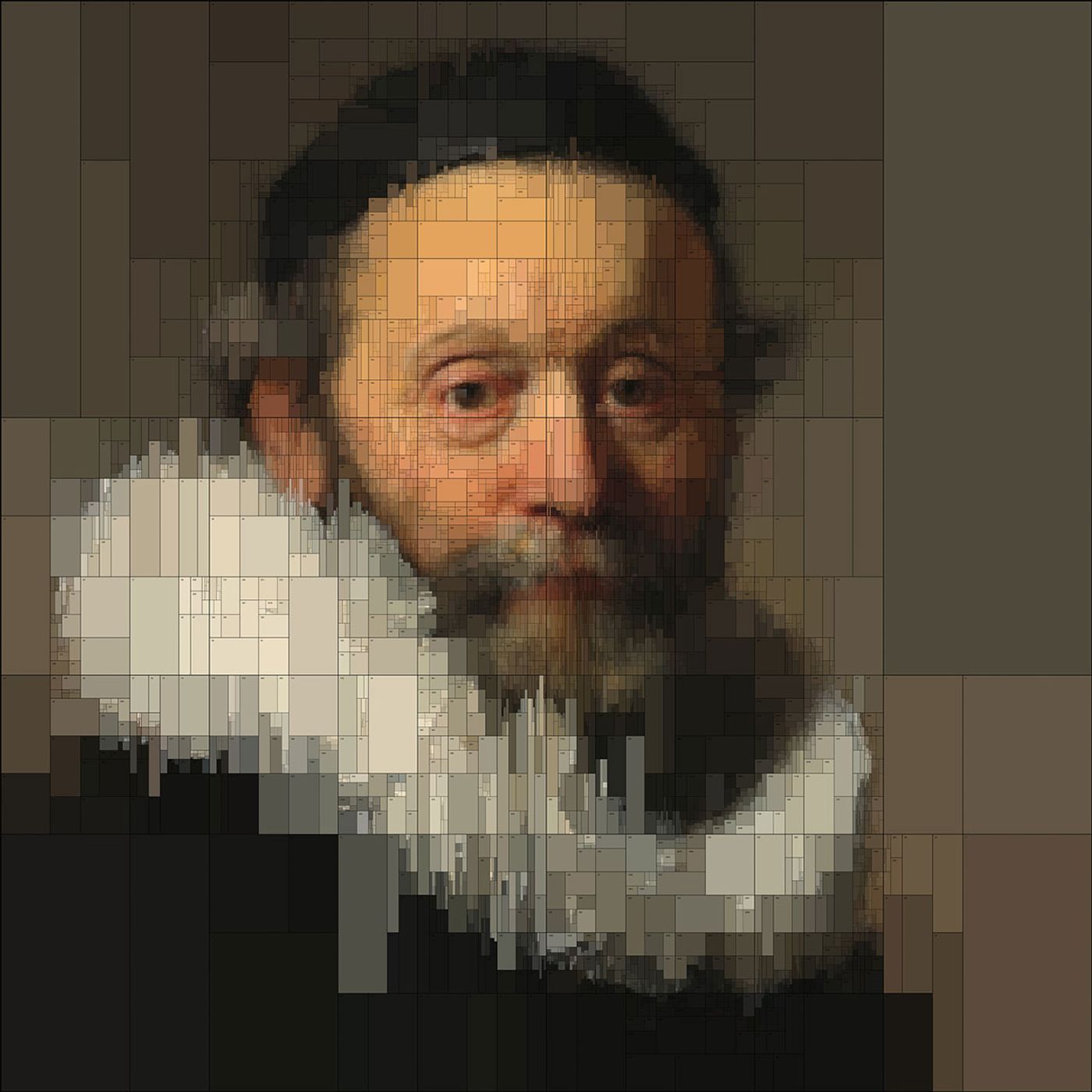

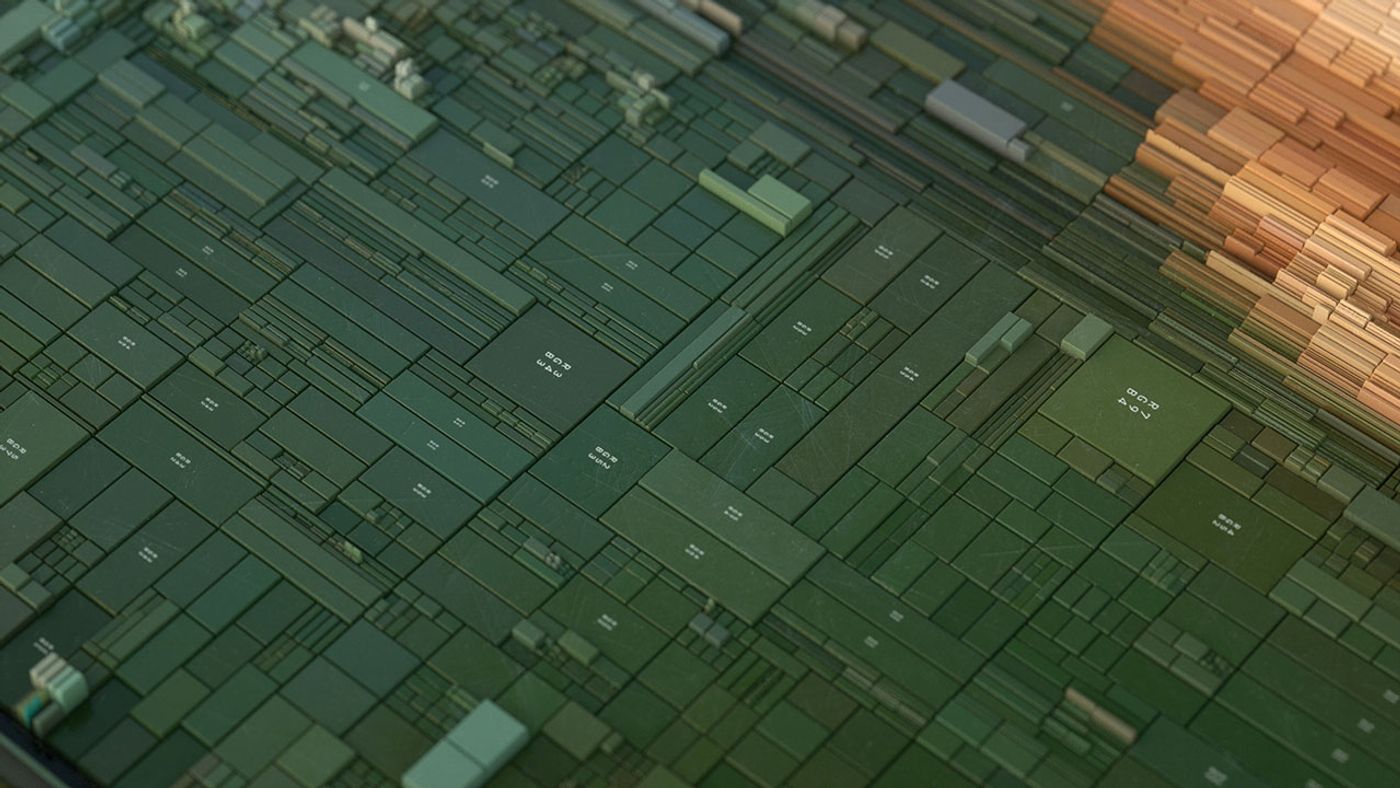

Johannes, from Portraits series by Dimitris Ladopoulos (Original painting - Portrait of Johannes Wtenbogaert by Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn, 1633).

Johannes (detail), from Portraits series by Dimitris Ladopoulos (Original painting - Portrait of Johannes Wtenbogaert by Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn, 1633).

The stark geometry and mechanical sensibility of the resulting images stands in direct contrast with the organic softness and human nature of the original portraits, which explains why Ladopoulos was drawn to these kinds of paintings as opposed to landscapes or still lifes. Moreover, it was an intriguing challenge to investigate how much deconstruction a portrait could sustain before its humanity was lost.

When it came to choosing which classical artworks to feed into his algorithm, the designer turned to one of his favourite portrait painters, the Dutch master Rembrandt, and in particular his 1633 portrait of Johannes Wtenbogaert. While searching for the right Rembrandt portrait, the artist came across Rembrandt Peale, a 19th century American painter whose 1820 portrait of his daughter Rosalba was the perfect female counterpart to that of Johannes. Despite being separated by about two centuries, the two paintings are characterized by a similar palette of earthy hues and sombre composition, while their two subjects, regardless of their age difference—Rosalba was in her early twenties when her father painted her whereas Johannes was 76—share the same pensive demeanour.

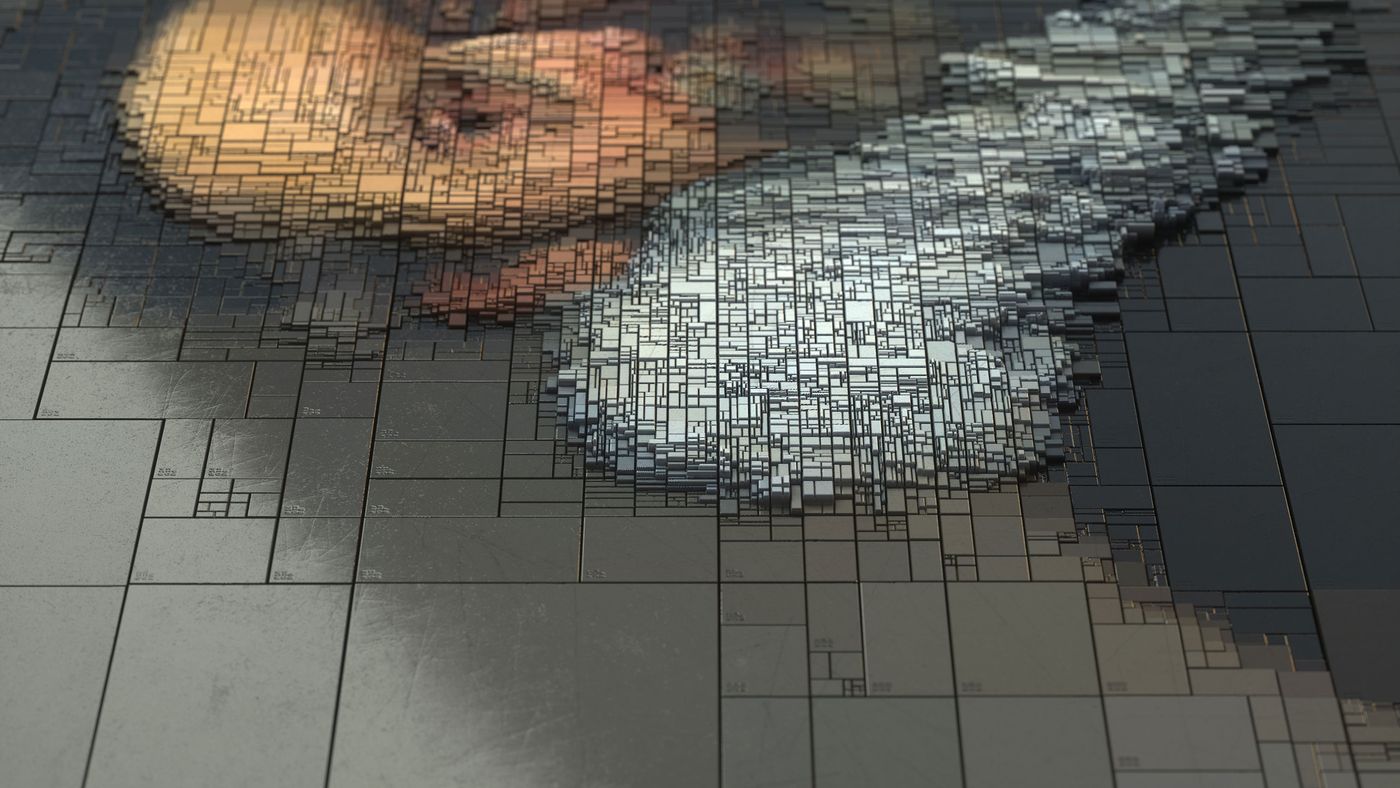

Johannes (detail), from Portraits series by Dimitris Ladopoulos (Original painting - Portrait of Johannes Wtenbogaert by Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn, 1633).

Johannes (detail), from Portraits series by Dimitris Ladopoulos (Original painting - Portrait of Johannes Wtenbogaert by Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn, 1633).

Johannes (detail), from Portraits series by Dimitris Ladopoulos (Original painting - Portrait of Johannes Wtenbogaert by Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn, 1633).

Johannes (detail), from Portraits series by Dimitris Ladopoulos (Original painting - Portrait of Johannes Wtenbogaert by Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn, 1633).

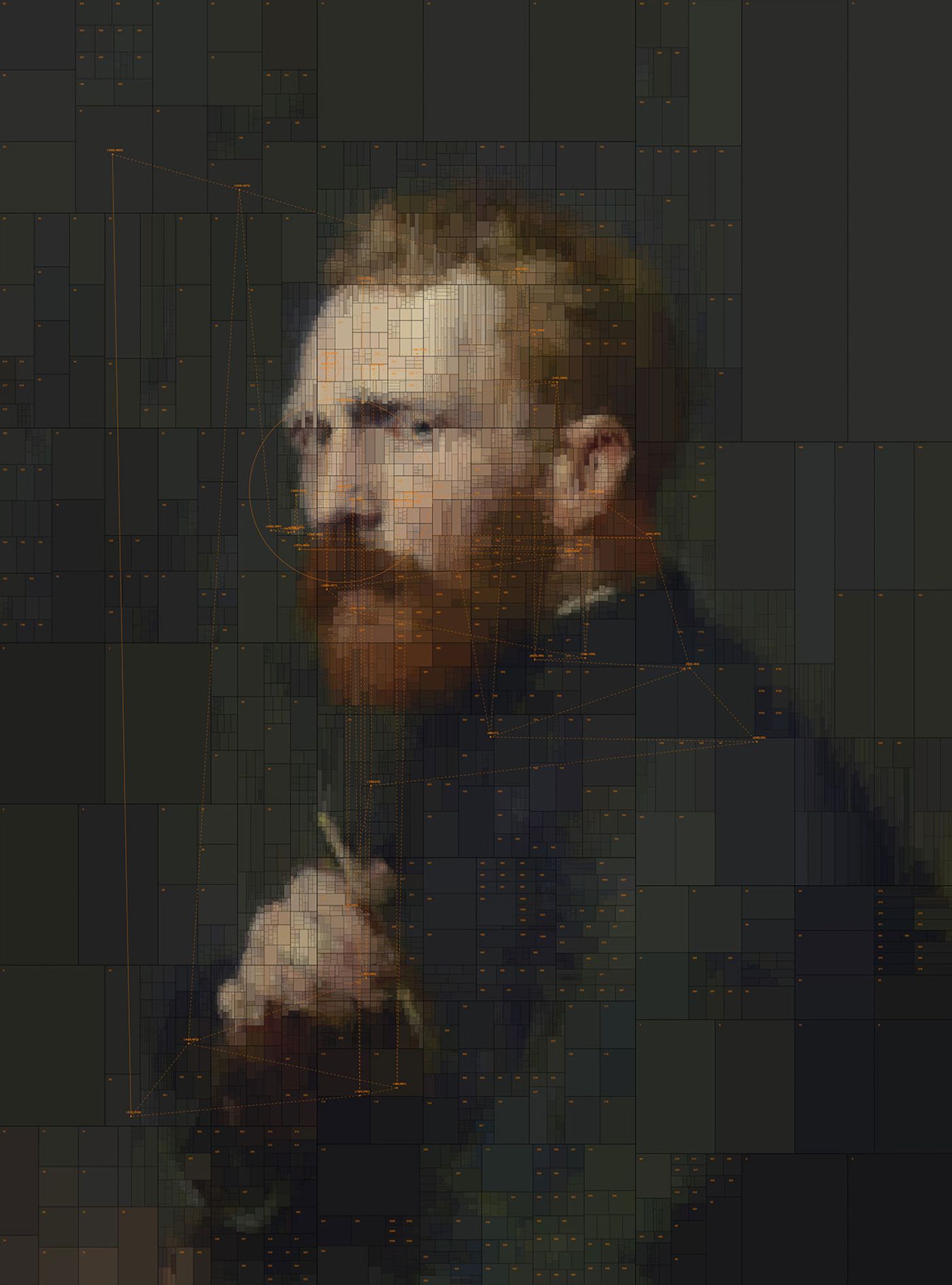

Joining this eccentric pair are ten more portraits that span the age of classical portraiture, from the iconic plasticity of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa and the exquisite photorealism of Vermeer’s Milkmaid, to the neoclassical austerity of The Princesse de Broglie by Ingres and the haunting imprssionism of Vincent van Gogh’s portrait by Australian painter John Peter Russell.

As you zoom in on the faces, the rendered portraits reveal great depths of detail, with some rectangular swatches being almost hair-like in stark juxtaposition to larger blocks found in the paintings’ backgrounds. What’s even more intriguing though is the software’s ability, guided by the designer’s preferences, to render the images in three-dimensional relief. The potential of this unique feature hasn’t been lost on Ladopoulos who is currently researching, in consultations with a few manufacturers, the most efficient way to produce his computational renderings, which will eventually grow to about ten images, in three-dimensions.

Albert, from Portraits series by Dimitris Ladopoulos (Original painting - The Princesse de Broglie by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, 1851–53).

Albert (detail), from Portraits series by Dimitris Ladopoulos (Original painting - The Princesse de Broglie by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, 1851–53).

Since the Renaissance, painters have oftentimes used technological means, from drawing frames and perspective machines to camera obscuras and curved mirrors, in order to perfect their highly detailed and realistic paintings. In fact, artist David Hockney has actually postulated that many of the old masters primarily relied on such optical instruments to realistically depict their subjects. So there is a kind of poetic justice to Ladopoulos’ project, which uses technology not to enhance the realism of the paintings but to subvert it.

Albert (detail), from Portraits series by Dimitris Ladopoulos (Original painting - The Princesse de Broglie by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, 1851–53).

Albert (detail), from Portraits series by Dimitris Ladopoulos (Original painting - The Princesse de Broglie by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, 1851–53).

Elizabeth Winthrop Chanler, from Portraits series by Dimitris Ladopoulos (Original painting by John Singer Sargent, 1893).

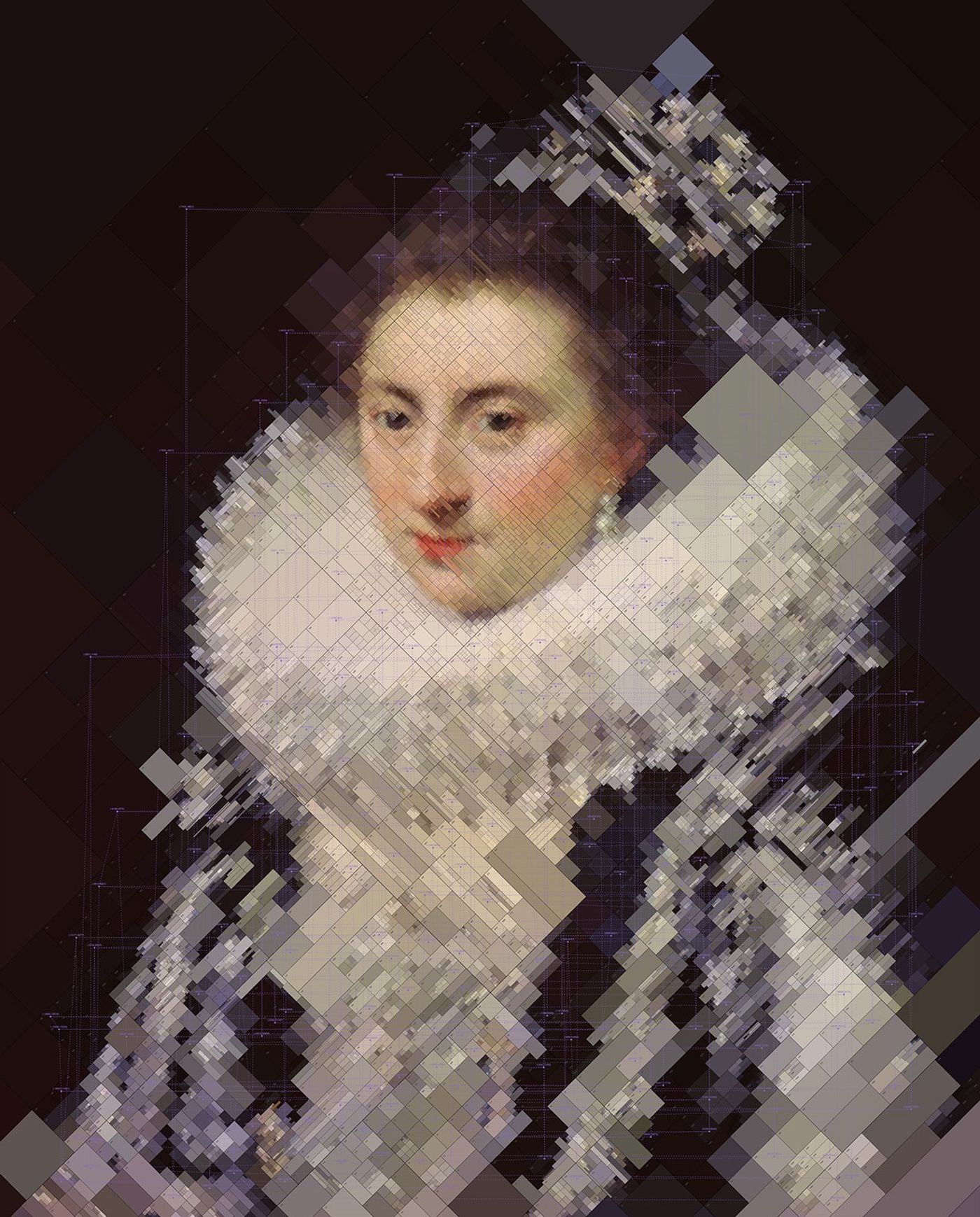

Portrait of Ernestine Yolande, from Portraits series by Dimitris Ladopoulos (Original painting by Jan Anthonisz van Ravesteyn, 1594-1663).

Rosalba (detail), from Portraits series by Dimitris Ladopoulos (Original painting - Portrait of Rosalba Peale by Rembrandt Peale, 1820).

Mona Lisa, from Portraits series by Dimitris Ladopoulos (Original painting by Leonardo da Vinci, 1503–06, perhaps continuing until 1517).

Mona Lisa (detail), from Portraits series by Dimitris Ladopoulos (Original painting by Leonardo da Vinci, 1503–06, perhaps continuing until 1517).

The Milkmaid, from Portraits series by Dimitris Ladopoulos (Original painting by Johannes Vermeer, 1657–1658).