Title

Bodys Isek Kingelez: City Dreams at MoMAPosted In

ExhibitionDuration

26 May 2018 to 01 January 2019Venue

MoMAOpening Hours

Daily 10:30 a.m.–5:30 p.m.Location

Telephone

+1 212 708 9400More Info

Curated by Sarah Suzuki

| Detailed Information | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title | Bodys Isek Kingelez: City Dreams at MoMA | Posted In | Exhibition | Duration | 26 May 2018 to 01 January 2019 |

| Venue | MoMA | Opening Hours | Daily 10:30 a.m.–5:30 p.m. | Location |

11 West 53 Street New York, NY 10019

United States |

| Telephone | +1 212 708 9400 | More Info | Curated by Sarah Suzuki | ||

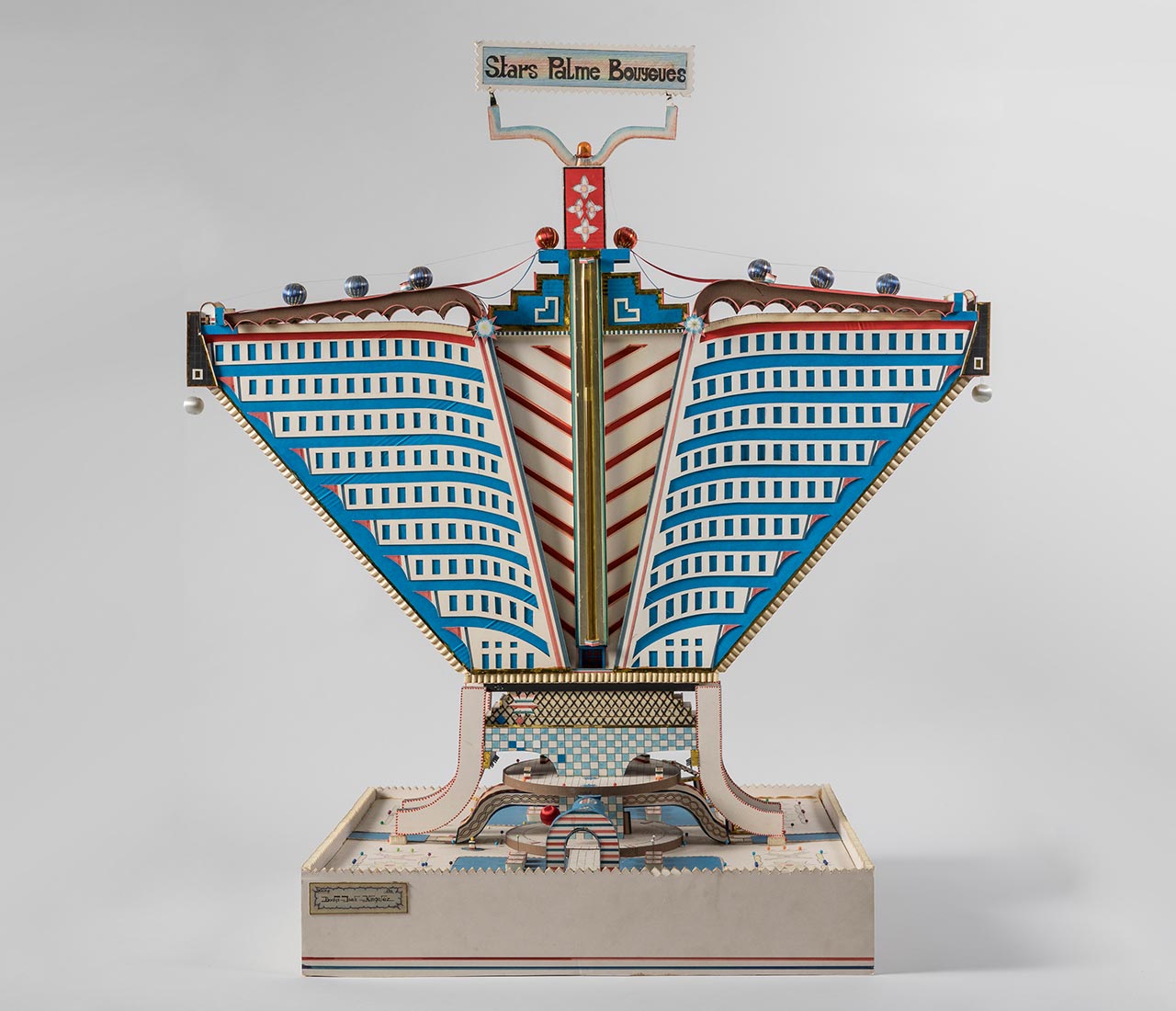

Bodys Isek Kingelez,. Stars Palme Bouygues, 1989. Paper, paperboard, and other various materials, 100 × 40 × 40 cm. van Lierde collection, Brussels. Vincent Everarts Photography Brussels

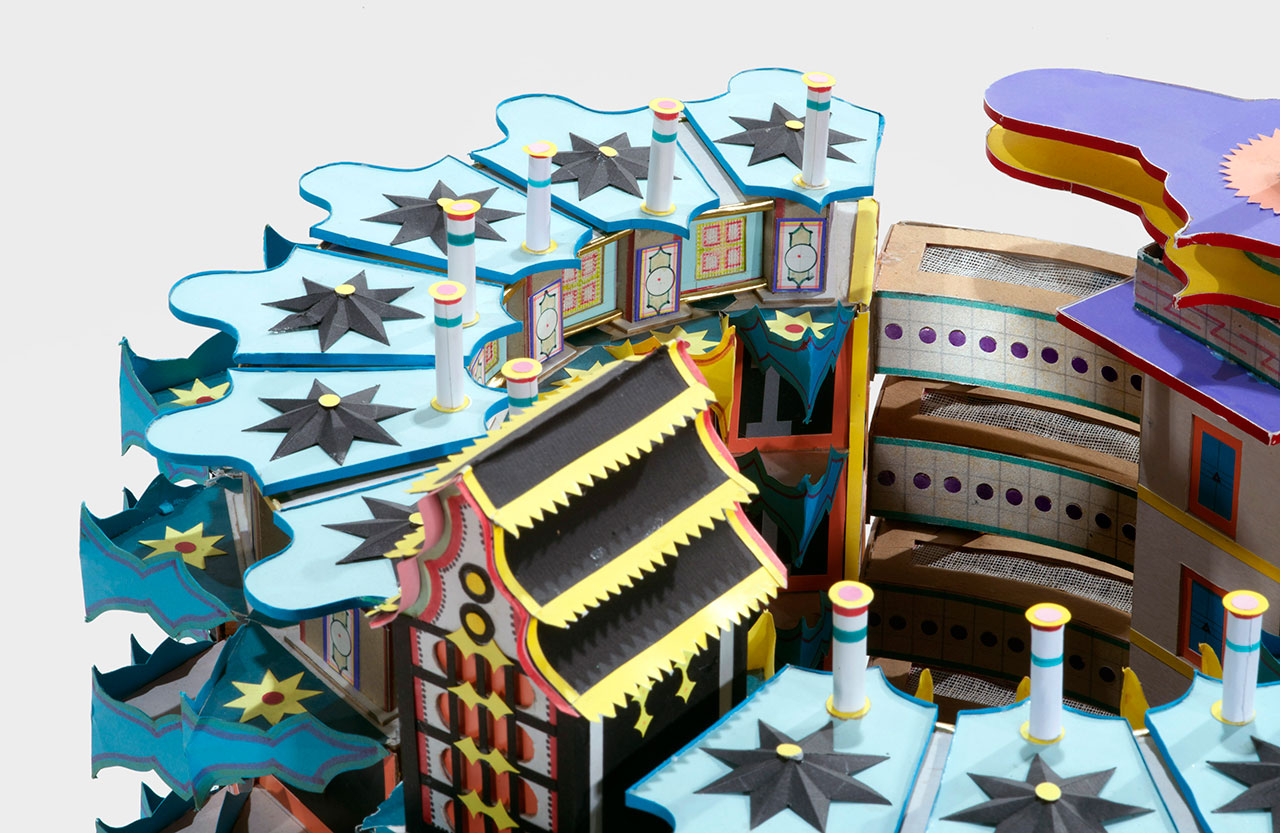

Bodys Isek Kingelez, Stars Palme Bouygues (detail), 1989. Paper, paperboard, and other various materials, 100 × 40 × 40 cm. van Lierde collection, Brussels. Vincent Everarts Photography Brussels.

Bodys Isek Kingelez,. Kimbembele Ihunga, 1994. Paper, paperboard, plastic, and other various materials, 130 × 185 × 320 cm. CAAC – The Pigozzi Collection, Geneva. © Bodys Isek Kingelez / Photo: Maurice Aeschimann. Courtesy CAAC – The Pigozzi Collection

Bodys Isek Kingelez, Paris Nouvel (detail), 1989. Paper, paperboard, and other various materials, 85 × 61 × 70 cm. Long-term loan from the Centre national des arts plastiques, France to the Château d’Oiron, France, FNAC 981003. © Cnap (France) / droits résérves; photograph by Frédéric Pignoux, Studio Ludo.

Born in 1948 in Kimbembele-Ihunga, a village in what was then the Belgian-Congo, Kingelez began his artistic endeavours in the late 1970s when he moved to Kinshasa, the capital of Zaire (the country's new name that would last until 1997). At the time he was also working as a restorer of masks and other tribal relics at the Institute of National Museum, an occupation quite different in sensibility from his artistic aesthetic but which nevertheless helped him perfect his craftsmanship skills and enhance his eye for detail.

In the mid-eighties, he left his job at the museum and devoted himself to art full time. His big break came in 1989 when he took part in a hugely influential 1989 group exhibition in Paris, “Magiciens de la Terre” which showcased Western and Third World artists with equal fervour. Meanwhile, his six month stay in the French capital, his first trip abroad, enriched his artistic sensibility and broadened his material palette.

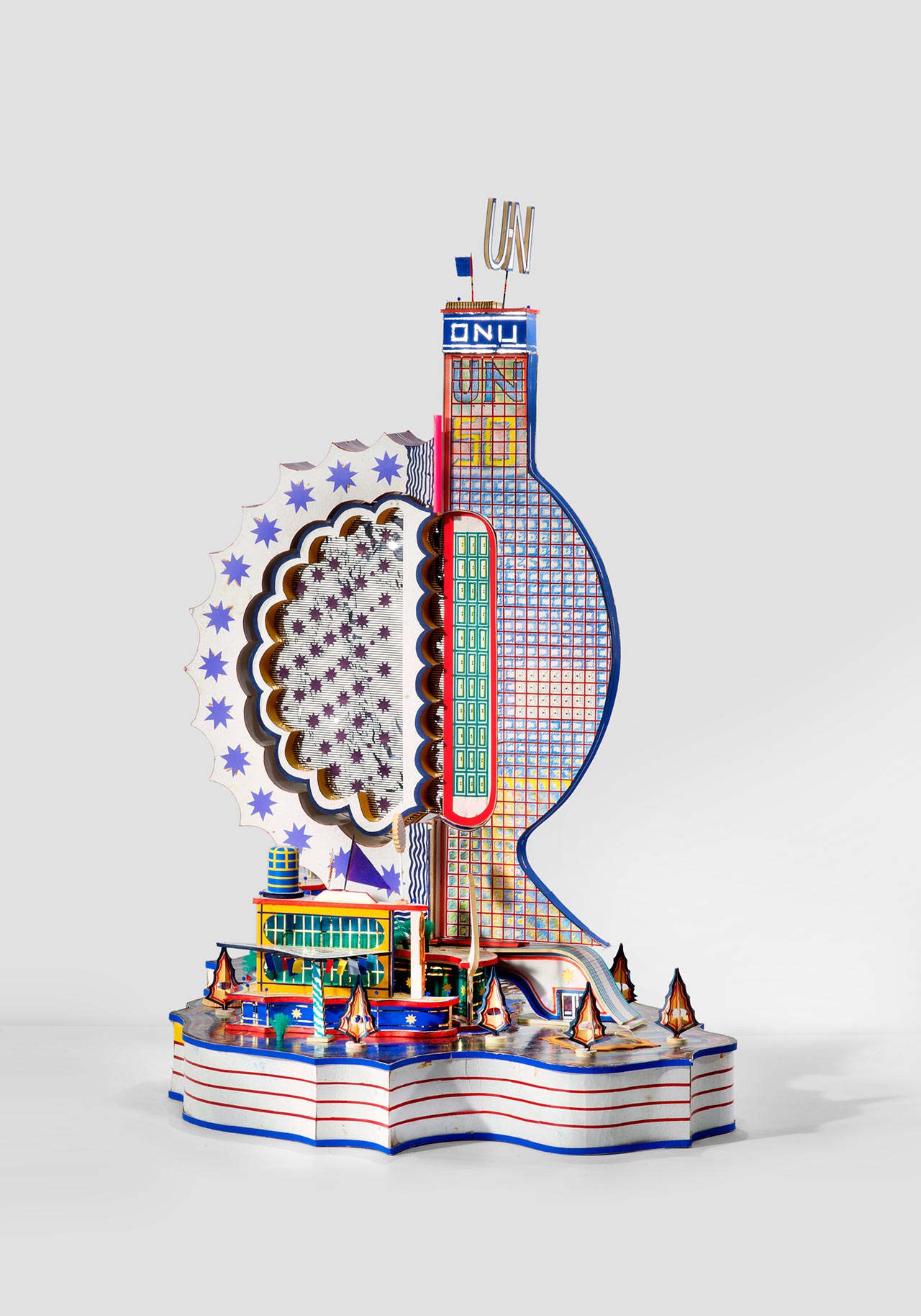

Bodys Isek Kingelez, U.N., 1995. Paper, paperboard, and other various materials, 91 × 74 × 53 cm, irreg. CAAC – The Pigozzi Collection, Geneva. © Bodys Isek Kingelez / Photo: Maurice Aeschimann. Courtesy CAAC – The Pigozzi Collection.

Bodys Isek Kingelez, Ville Fantôme, 1996. Paper, paperboard, plastic and other various materials, 120 × 570 × 240 cm. CAAC – The Pigozzi Collection, Geneva. © Bodys Isek Kingelez / Photo: Maurice Aeschimann. Courtesy CAAC – The Pigozzi Collection.

Bodys Isek Kingelez, Ville Fantôme (detail), 1996. Paper, paperboard, plastic and other various materials, 120 × 570 × 240 cm. CAAC – The Pigozzi Collection, Geneva. © Bodys Isek Kingelez / Photo: Maurice Aeschimann. Courtesy CAAC – The Pigozzi Collection.

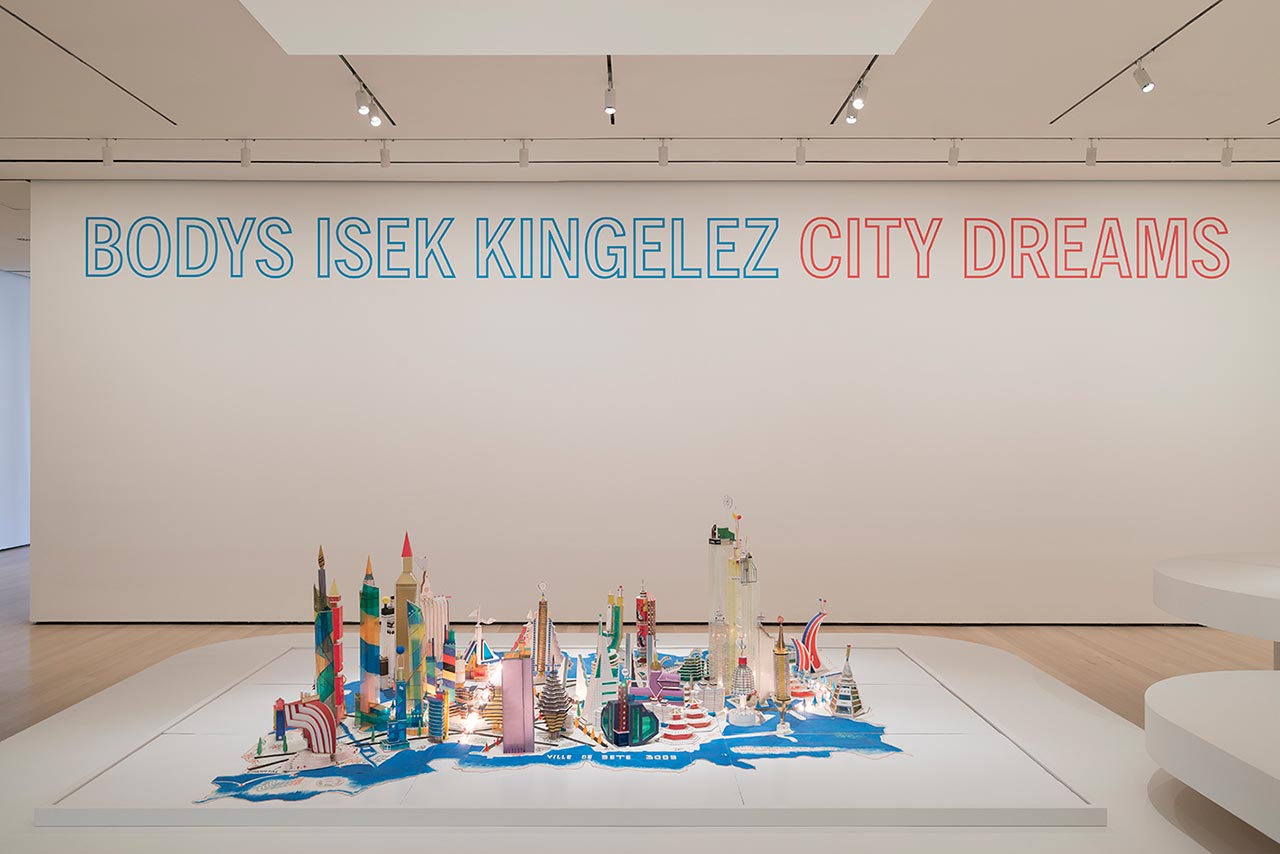

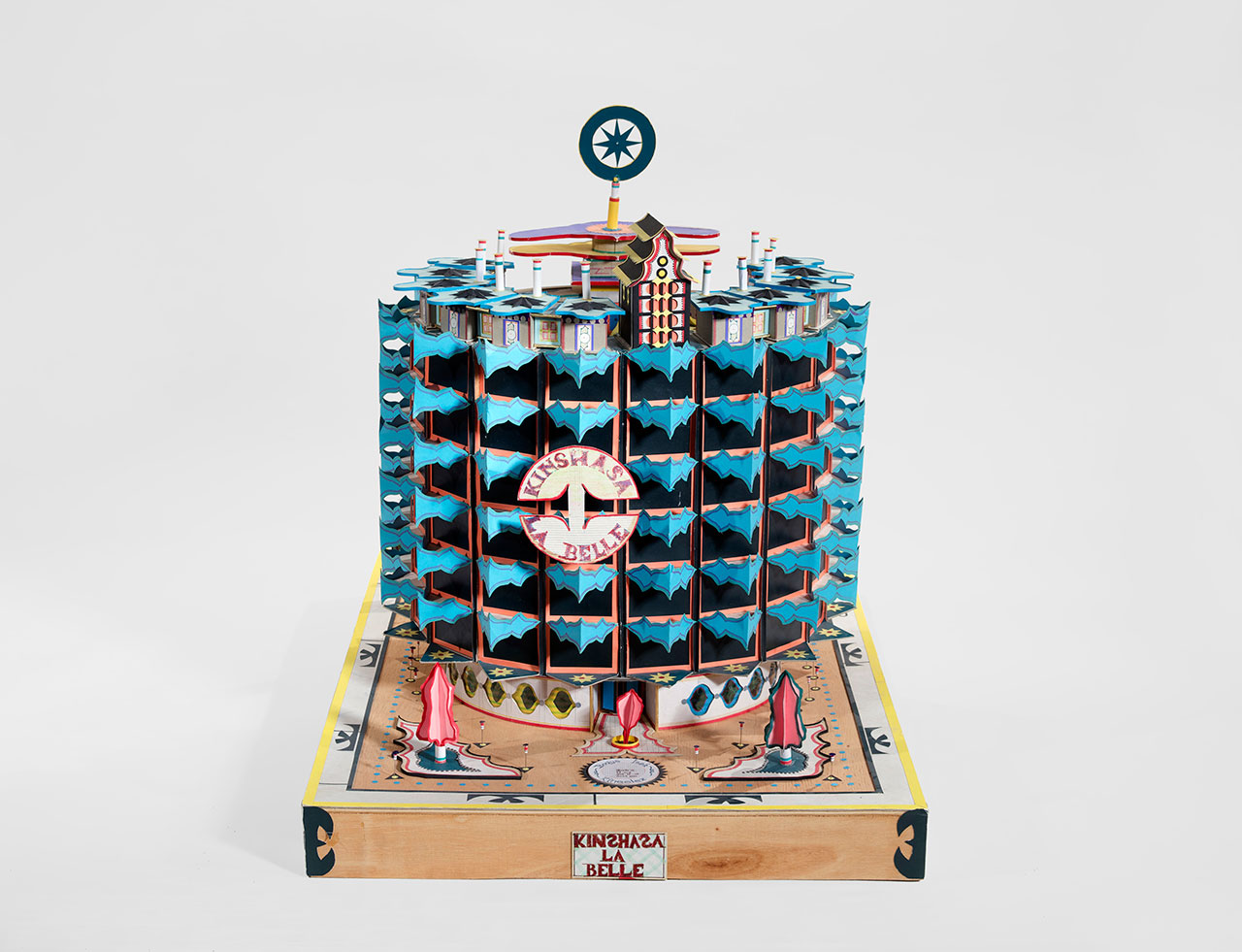

The 33 exhibits on display at MoMA, which range from single-building models, to spectacular sprawling cities, and to futuristic late works created out of increasingly unorthodox materials, constitute Kingelez’s visionary blueprint for the cities of his country and the world at large. Featuring sleek skyscrapers, majestic office buildings, fanciful train stations and ostentatious banks, bristling with fins, lanterns, parapets and colonnades, and adorned with ingenious decorative motifs of geometrical and floral intricacy, the models constitute an enthralling wonderland of kaleidoscopic pizzazz.

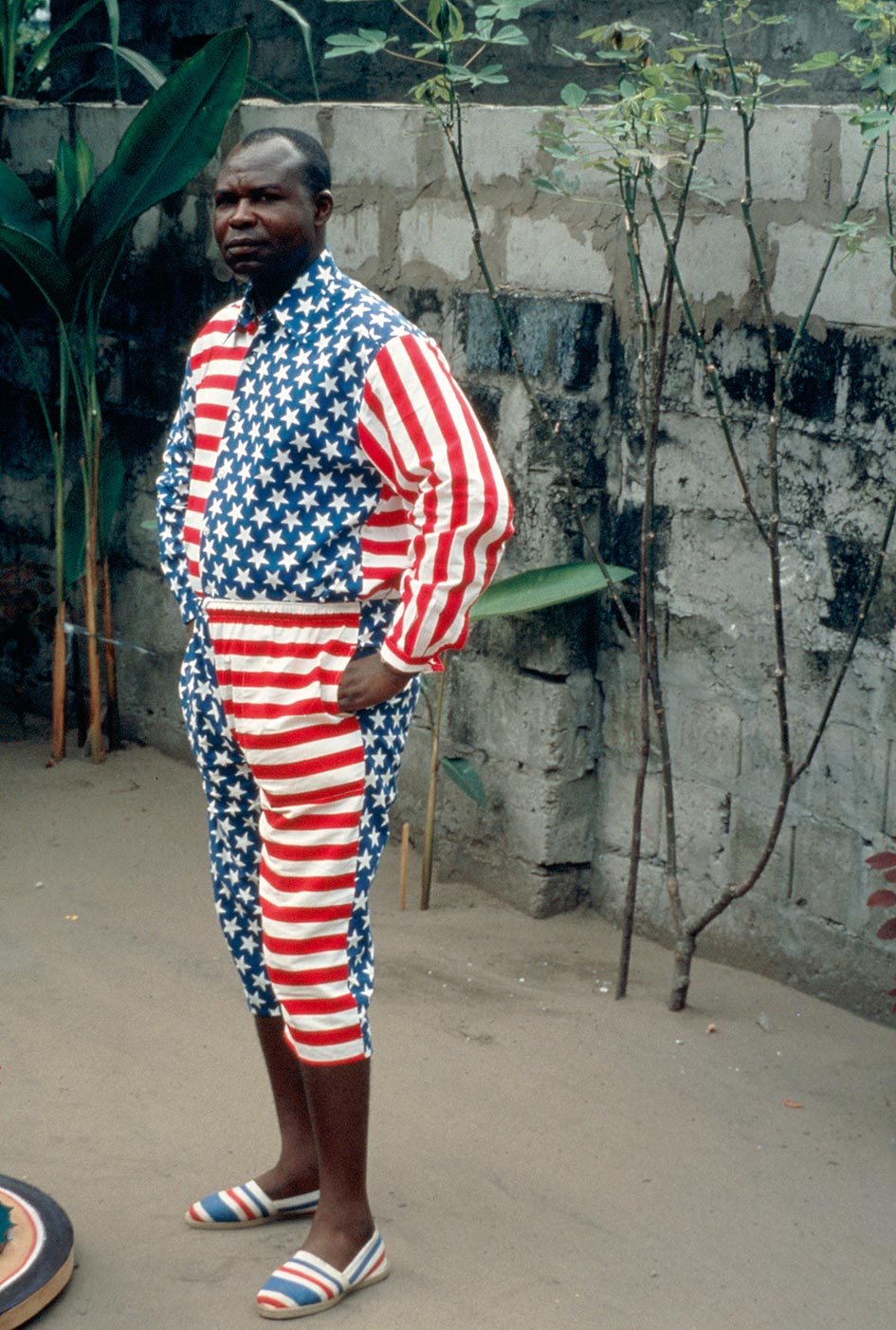

“A building without colour is like a naked person”, Kingelez famously said, and true to his word the maquettes are characterized by an exuberant colour palette based on red, yellow, and green, the colours of the national flag at the time (the flag has since changed), which is both carnivalesque and sophisticated. Interestingly, his chromatic flamboyance was also reflected in his eccentric fashion sense despite the fact that he was somewhat of a recluse.

Bodys Isek Kingelez, Ville de Sète 3009 (detail), 2000. Paper, paperboard, plastic, and other various materials, 80 × 300 × 210 cm. Collection Musée International des Arts Modestes (MIAM), Sète, France. © Pierre Schwartz ADAGP; courtesy Musée International des Arts Modestes (MIAM), Sète, France.

Bodys Isek Kingelez, Nippon Tower, 2005. Paper, paperboard, plastic, and other various materials, 67 × 34 × 22 cm, irreg. Courtesy Aeroplastics Contemporary, Brussels. Vincent Everarts Photography Brussels.

Undoubtedly the most impressive of the artist’s works, which is also widely considered to be his masterpiece, is “Ville Fantôme” (1996), a nearly six metre sprawl of about 50 structures, including a bridge and an airport, serviced by a network of roads, pathways, train tracks and bridges. Enhanced by an overhead mirror that reveals even more of the astounding complexity of this work which took two years to complete, the miniature city can be also explored through a headset that offers visitors the opportunity to take a self-guided virtual-reality tour. Closer to home, in “Kimbembele Ihunga” (1994), the artist re-imagined the rural village he grew up in as a futuristic metropolis complete with banks, restaurants, and a soccer stadium, while in “The Scientific Center of Hospitalisation the SIDA” (1991), he references an AIDS epidemic in Zaire without succumbing to gloom.

Installation view of Bodys Isek Kingelez: City Dreams, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, May 26, 2018–January 1, 2019. © 2018 The Museum of Modern Art. Photo by Denis Doorly.

Installation view of Bodys Isek Kingelez: City Dreams, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, May 26, 2018–January 1, 2019. © 2018 The Museum of Modern Art. Photo by Denis Doorly.

Installation view of Bodys Isek Kingelez: City Dreams, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, May 26, 2018–January 1, 2019. © 2018 The Museum of Modern Art. Photo by Denis Doorly.

Following Congo’s independence from Belgium in 1960, there was great hope for building a free, just and prosperous African society, centred on the development of the new nation’s capital, aspirations which were soon eclipsed by dictatorship, corruption and civil unrest. In this respect, Kingelez’s work embodies more than anything the lofty plans of post-independence Congo, as well as the universal desire for a brighter future, with the artist himself having boastfully claimed that his work contributed towards ‘‘lasting peace, justice and universal freedom”. And yet, one cannot help but detect in his exuberant, over-the-top visions of the future a satirical commentary on his country’s dashed ambitions as well as the excessive consumption of modern societies.

More observant visitors will detect that Kingelez often worked his name or initials into the buildings’ facades or signs—modesty was not one of the artist’s strong suits, after all he described himself at one time as “a small god”—which in the age of the Trump presidency makes his work ever more relevant today. Viewed in conjunction with the sleek Trump Tower and the other swanky eponymous venues that have become newsworthy settings for backroom deals, corruption and authoritarianism, Kingelez’s architectural flights of fancy are both a skit on and a warning against the excess of power and money, but on a more visceral level they offer a joyful reprieve from our anxiety-laden lives.

Bodys Isek Kingelez, Kinshasa la Belle, 1991. Paper, paperboard, and other various materials, 63 × 55 × 80 cm. CAAC – The Pigozzi Collection, Geneva. © Bodys Isek Kingelez / Photo: Maurice Aeschimann. Courtesy CAAC – The Pigozzi Collection.

Bodys Isek Kingelez,Kinshasa la Belle (detail), 1991. Paper, paperboard, and other various materials, 63 × 55 × 80 cm. CAAC – The Pigozzi Collection, Geneva. © Bodys Isek Kingelez / Photo: Maurice Aeschimann. Courtesy CAAC – The Pigozzi Collection.

Bodys Isek Kingelez, Belle Hollandaise, 1991. Paper, paperboard, and other various materials, 55 × 80.5 × 56 cm. Collection Groninger Museum. Photograph by Marten de Leeuw.

Bodys Isek Kingelez in Kinshasa, 1990. Courtesy André Magnin, Paris. Photo by André Magnin.