Ben Johnson

Room of the Niobids II

2013

Acrylic on canvas

71 x 98 in / 180 x 252 cm.

Ben Johnson

Patio de los Arrayanes

2015

Acrylic on canvas

220 x 220 cm.

Ben Johnson

Approaching the Mirador

2013

Acrylic on canvas

89 x 59 in / 225 x 150 cm.

To achieve the accuracy observed even in the minutest details of his paintings, Johnson follows a process that involves drawing, multiple layers of stencilling and meticulous colour-mixing. The sheer effort and time required to complete these paintings is put into perspective only when one listens to the artist himself describe his process: in a recent BBC documentary, Johnson explains that no less that 25 layers of stencilling were required to complete a single column in one of his elaborate Alhambra palace paintings, and that it took ten people three years and approximately 60,000 hours of work to complete the monumental Liverpool Cityscape painting (2008) noting that if a single person were to do the same amount of work, it would have taken them 17 years to complete the massive five-meter-wide painting.

Ben Johnson

The Liverpool Cityscape (progress)

2008

Acrylic on canvas

96 x 192in / 244 x 488cm.

Photo courtesy of the artist.

Ben Johnson

Room of the Revolutionary (progress)

2014

Acrylic on canvas

89 x 59 in / 225 x 150 cm.

Photo courtesy of the artist.

Ben Johnson

Looking Back to Richmond House (progress)

Photo courtesy of the artist.

What strikes us most about Johnson’s paintings is their flatness: even though they depict densely-built urban landscapes and the elaborate geometry of real, three-dimensional spaces, their details are rendered with the same care and clarity whether they are in the foreground or the background. This elimination of distance and acute perception of a vast area depicted with the same intensity is something that the human eye is normally unable to do (only the eye of a god or some superhuman entity could possible take all this detail in with a single glance). It is therefore perhaps no coincidence that one of Johnson’s more recent undertakings is the study and depiction of sacred geometry in Islamic architecture, in turn an art that consciously aims to reveal the limitations of human perception and the vastness of the natural world —and therefore, God’s own infinity. Through their overwhelming detailing and unthinkable amount of labour required to complete them, Johnson’s paintings give us the opportunity to step out of our normal perception of time and space, and become, even if for a moment, divinely omnipresent.

Ben Johnson

Hong Kong Panorama

1997

Acrylic on canvas

6x12ft / 1.83x3.66m.

Ben Johnson

Jerusalem, The Eternal City

1999 / 2000

Acrylic on canvas

90x180in / 2029x 4057cm.

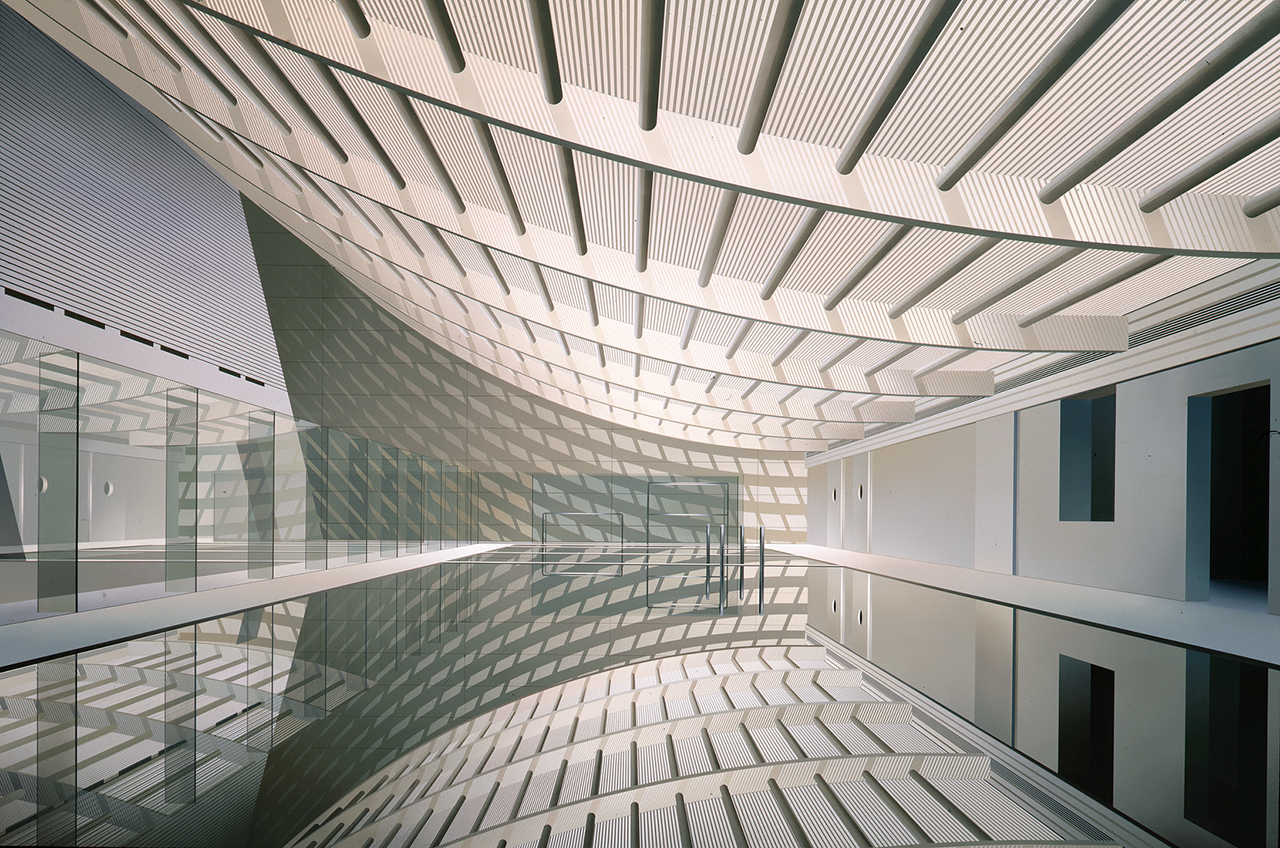

Ben Johnson

The Inner Space

2001

Acrylic on linen

40 x 60 in / 102 x 152 cm.

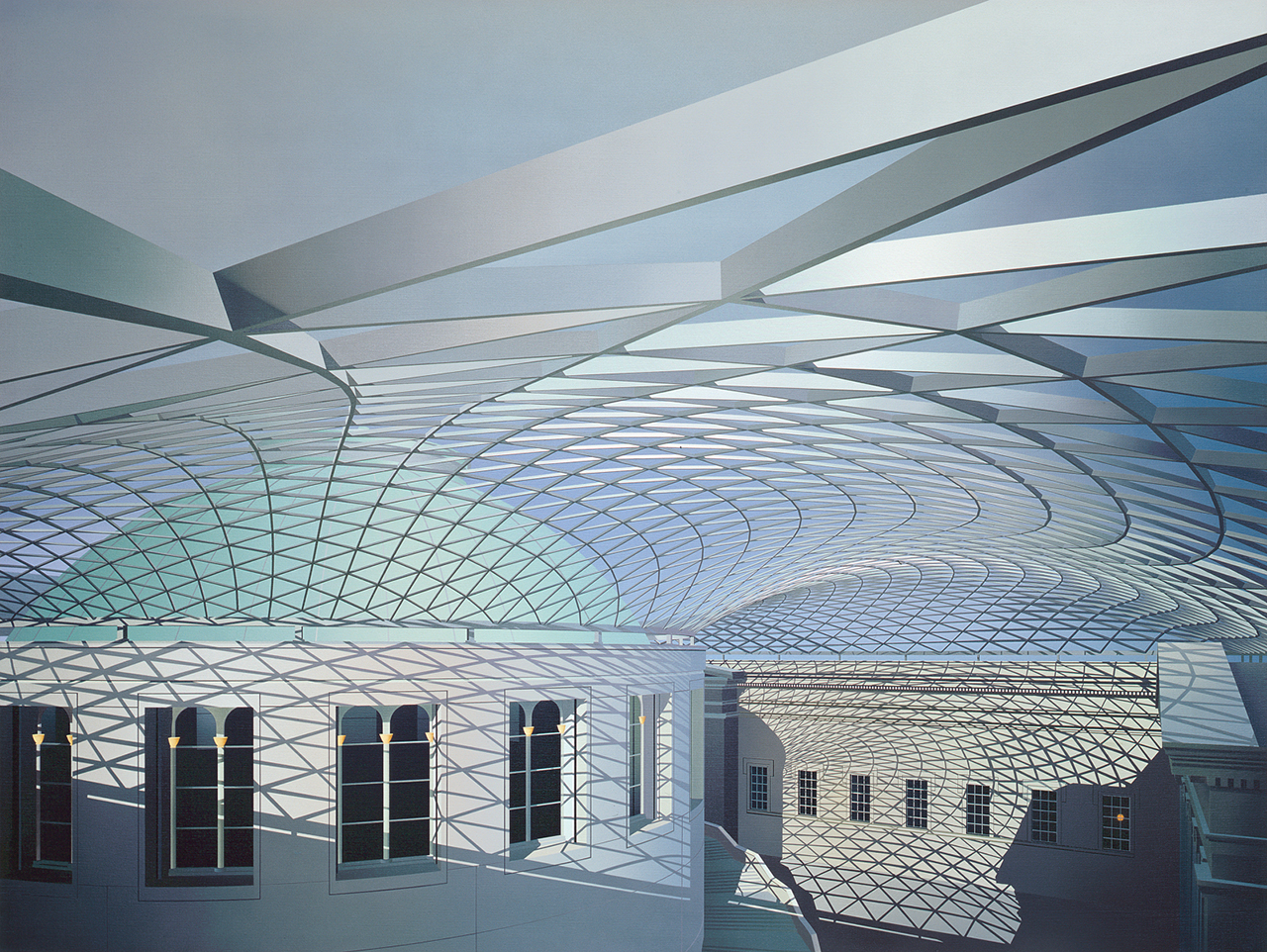

Ben Johnson

British Museum Great Court

2002

Acrylic on linen

59x79in / 150x200cm.

Ben Johnson

Study for Far Horizons I

2009

Acrylic on canvas

20 x 20 in / 50 x 50 cm.

Ben Johnson

Tokyo Pool

2006

Acrylic on canvas

54x81in / 137 x 206 cm.

Ben Johnson

IBM North Harbour

1984

Acrylic on canvas

78x117in / 198x297cm.

Ben Johnson

The Unattended Moment

1993

Acrylic on canvas

72x96in / 184x243cm.

Ben Johnson

The Rookery, Chicago

1995

Acrylic on canvas

91x91in / 231x231cm.

Ben Johnson

Double Doors, France

1979

Acrylic on canvas

84x56 1/4in / 213x104cm.

Ben Johnson

Three Moments of Illumination

1998

Acrylic on canvas, triptych

108x170in / 2740x4320cm.

Ben Johnson

Through Marble Halls

1994

Acrylic on canvas

55x72in / 139x183cm.

Ben Johnson

Reflections on Past and Present, Paris

1996

Acrylic on canvas

100x80in / 254x203cm.