A Conversation with Marcin Rusak: An Alchemist of Time, Material and Memory

Words by Eric David

Location

A Conversation with Marcin Rusak: An Alchemist of Time, Material and Memory

Words by Eric David

Flowers have always been a rich source of inspiration for artists and designers throughout the ages. From the floral motifs of Roman mosaics and Art Nouveau’s nature-inspired ornamentation, to the lush still lifes of the Dutch Golden Age painters, the vibrant paintings of Georgia O’Keeffe and the sensual photographs of Robert Mapplethorpe, flowers have been immortalized as symbols of beauty, fragility, and the passage of time across cultures and centuries. Polish multidisciplinary artist and designer Marcin Rusak takes this enduring fascination to an entirely different level where flowers are not only a source of inspiration but the very fabric of his creations.

Raised in a family of flower growers, Rusak has long been captivated by the fleeting nature of flowers—how they bloom, wither, and ultimately vanish. This awareness of time and transience informs both his creative process and conceptual explorations. What began as an experiment in repurposing floral waste evolved into a signature practice where organic matter is transformed into extraordinary sculptures, furniture pieces and installations that challenge our perceptions of value, consumption, and time, as well as attempt to redefine our relationship with nature—not as something to simply admire, but as something to embrace in all its imperfection and transformation.

Marcin Rusak portrait. Photography by Kasia Bielska. © Marcin Rusak - Swidno Foundation.

Swindo Foundation. Photo by Ada Zielinska. Courtesy of Marcin Rusak Studio.

Swindo Foundation. Photo by PION Studio. Courtesy of Marcin Rusak Studio.

At the heart of his practice lies a relentless spirit of experimentation. His Warsaw-based studio operates as a laboratory where botany meets craftsmanship, and scientific inquiry fuels artistic expression. Whether embedding leaves into resin, turning flowers into ash and then encasing them in glass, oxidizing metal surfaces, or designing objects that evolve over time, Rusak embraces nature’s cycles as both a concept and a medium. His hybrid approach—merging traditional crafts, industrial techniques, and digital fabrication—results in one-of-a-kind pieces that blur the boundaries between art, design, and material research.

Rusak's vision extends to larger explorations of space and experience. His Swidno Foundation, housed in a once-abandoned 18th century villa an hour’s drive from Warsaw, serves as a site for artistic experimentation and ecological reflection, reinforcing his commitment to sustainability and material storytelling. Yatzer recently caught up with Rusak to talk about his ever-evolving body of work, the challenges of material innovation and his return to Milan Design Week after a three-year hiatus.

Answers have been condensed and edited for clarity.

Swindo Foundation. Photo by Bill Stamatopoulos for Yatzer. Courtesy of Marcin Rusak Studio.

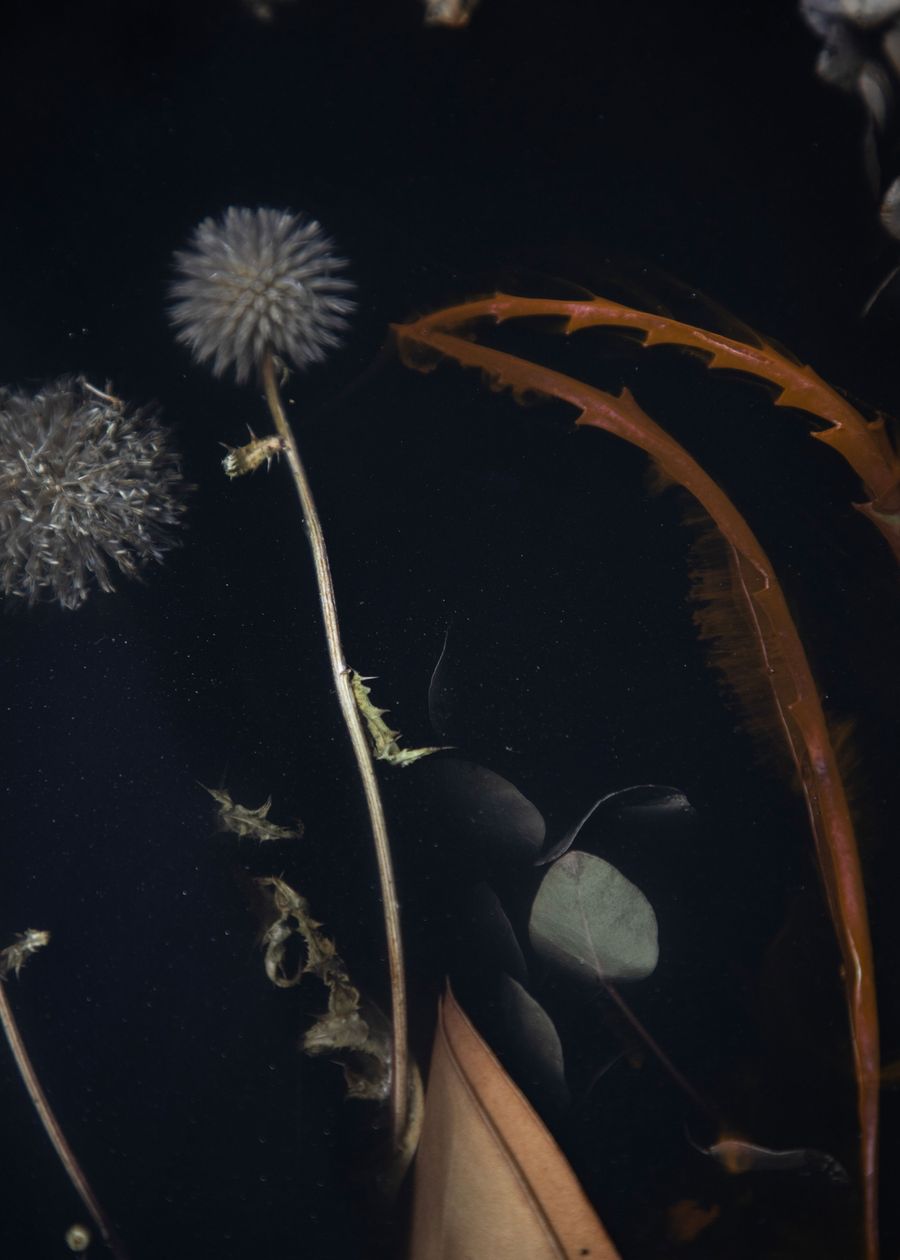

Protoplasting Nature, 04 (detail). Selected and processed leaves, resin, steel. Photo © Marcin Rusak Studio.

Where did your fascination with the natural world originate, and how has it shaped your evolution as an artist and designer?

It all boils down to rediscovering my heritage whilst studying at the RCA in London. When a tutor asked me to think of a piece that struck an emotional cord, I immediately thought of the giant, carved baroque wardrobe, or Danziger Schapp, that belonged to my grandfather. As a flower grower, he committed himself entirely to breeding new species: he would sleep all day and work at night, following the vital cycles of the flowers. I tried to retrace his fascination, wandering around the famous London flower markets after hours, collecting dead plants that went unsold and experimenting with them in the studio. I started asking myself: what is it that compels us to manipulate nature? And why are we so fascinated with plants to the point that we immortalise them in our creations? This led me to explore the cut flower market further, and how it worked behind-the-scenes. After all, flowers are highly manipulated commodities that we either buy out of vanity, or to fulfil our needs for sensual pleasure, status, style… etc.

On the other hand, there is the wilderness that has attracted me ever since I was a little boy wandering around my grandfather’s glasshouses which, by the time I was an adolescent, had been closed down, lay derelict and abandoned, overgrown with weeds. This self-replicating system of growth and decay which is both hostile and extremely appealing is something I find solace and inspiration in.

Photo of orchids from the family archives of Marcin Rusak's grandfather. Courtesy of Marcin Rusak.

Photo of orchids from the family archives of Marcin Rusak's grandfather. Courtesy of Marcin Rusak.

Flora, Credenza 276. Selected and processed real flowers and leaves, resin, oak. Photo © Marcin Rusak Studio.

Flora, Credenza 183 (detail). Selected and processed real flowers and leaves, resin, oak. Photo © Marcin Rusak Studio.

Monster Flower 01. Cast aluminium, stainless steel. Photo © Marcin Rusak Studio.

Flowers feature prominently in your work, both in terms of materiality and decoration. What do you find most fascinating about them, and how do they serve as both a subject and a medium in your artistic narrative?

The research I conducted on genetic manipulations, and the whole global market system related to plants has very much informed my practice, resulting in works such as the Monster Flower, which symbolises all the genetic manipulations that flowers are subjected to in order to meet the various contradictory assumptions of flower growers, sellers and consumers, be it a straight stem that enables transportation, a more vivid colour or a longer vase life.

Flowers allow me to speak about what is important for me: about why we create, and what and why we collect. The works I create depict ephemerality, preservation and decay; taking real plants as a means to talk about what is important to me underlines these notions, framing it in a poetic and aesthetic context. Floral ornamentation is something that dates back to the ancient times, it’s been part of our civilisation, but with the crises we face related to both climate change and consumerism, it no longer serve as mere decoration–it now takes so much more meaning and contexts.

Exhibition view, Unnatural Practice, Milan, 2022. Photo by DSL Studio.

Tephra Credenza 225. Selected and processed flowers and leaves, steel wire, jute fabric, zinc, bronze, brass. Photo © Marcin Rusak Studio.

Tephra Credenza 225 (details). Selected and processed flowers and leaves, steel wire, jute fabric, zinc, bronze, brass. Photo © Marcin Rusak Studio.

Your work explores the tension between permanence and impermanence, preservation and decay. How do you translate these themes when it comes to choosing materials or deciding which artistic process you’re going to adopt?

I am fascinated by nature’s ability to resurrect: it is the constant cycle of creation and decay that I try to recreate and observe within the materials I develop in the studio. You might not know it, but the most successful material I invented, the Flora Temporaria, which I’ve used in my functional pieces, started off as a way to encapsulate the slow decay of plants within a more stable and unchanging material, i.e. resin. I imagined injecting bacteria that would slowly consume the plants within the material, leaving silvery voids filled with sunlight. This changed entirely when I experimented with adding pigment to the mixture, achieving a material that is as decorative as it is symbolic.

I also like to think that through my work I educate the audience to invest more care and attention into the pieces they surround themselves with. For instance, the Perishable Series, made with waste flowers and shellac and often reinterpreting archetypal collectable items such as vases, are totally stable in a controlled environment, but when you expose them to excess sunlight or moisture, they morph, and potentially collapse or disintegrate. It is up to their owner, or custodian, to decide which direction to pursue.

Flora, Coffee Table 218 (detail). Selected and processed real flowers and leaves, resin, steel, bronze in dark patina colour. Photo © Marcin Rusak Studio.

Flora, Coffee Table 218. Selected and processed real flowers and leaves, resin, steel, bronze in dark patina colour. Photo © Marcin Rusak Studio.

Flora, Low Coffee Table 132 (detail). Selected and processed real flowers and leaves, resin, steel. Photo © Marcin Rusak Studio.

Flora, Monolith 190. Selected and processed real flowers and leaves, resin. Photo © Marcin Rusak Studio.

Swindo Foundation. Photo by Bill Stamatopoulos for Yatzer.

Marcin Rusak in his Studio. Photography by Kasia Bielska. © Marcin Rusak - Swidno Foundation.

Experimentation is an integral part of your practice. What drives your curiosity, and how do you balance control with unpredictability in your process?

My work is definitely research-driven, both in terms of the materials I choose or develop for each project, my hands-on involvement in the process, as well as the partnerships I establish with external researchers, scientists or institutions. Most of the time, my self-initiated work starts with open-ended prerogatives, so naturally, we often deviate from the initial idea during the process.

When it comes to unpredictability, for me this is an inevitable part of the trial-and-error mindset. Take my Protoplasting Nature pieces for instance; when we first began experimenting with the metallisation process, the specially processed exotic leaves that we applied onto a hand-welded steel scaffolding caught on fire, an event that was rather spectacular, but also a bit dangerous at the same time. It took me a while to understand the do’s and don’ts, and we’re still learning with every step we take.

Swindo Foundation. Photo by Bill Stamatopoulos for Yatzer.

Swindo Foundation. Photo by Bill Stamatopoulos for Yatzer.

Swindo Foundation. Photo by Bill Stamatopoulos for Yatzer.

Your studio is often described as a laboratory. How do you approach material innovation, and what challenges go hand in hand with developing unique techniques in-house?

I’m constantly exploring new ways to engage with materials, especially those rooted in the natural world. I try to keep an open mind, observing the environment around me, and working closely with my entire team which consists of material specialists, engineers, and humanities majors. Trying out a new material involves not only hands-on manipulation, but also broader research into the cultural or economic aspects of it. This is true, for instance, regarding the recent research we did on amber and tree resins.

We learned, amongst other things, that resin sourcing was an important part of the Polish economy up until the early 1990s, and, perhaps counterintuitively, it helped prevent deforestation which is now affecting the country. Now, with the rise of synthetic alternatives, resin-derived materials such as colophony have mostly been forgotten, and are presently used only in small economic niches. I believe artists and designers highlighting those broad contexts may lead to a rethinking of the strategies that were abandoned in the past.

Swindo Foundation. Photo by Bill Stamatopoulos for Yatzer.

Swindo Foundation. Photo by Bill Stamatopoulos for Yatzer.

Regarding the challenges of developing unique techniques in-house, I often find that not all of the materials or processes that we explore are studied fully—some are left behind at the concept stage, waiting for new opportunities or suitable projects to be developed further. It is a long-term investment where we learn as we go.

Marcin Rusak in his Studio. Photo © Carpenters Workshop Gallery.

Marcin Rusak in his Studio. Photo © Carpenters Workshop Gallery.

Flora, Cabinet 190 (detail). Selected and processed real flowers and leaves, resin, stainless steel. Photo © Marcin Rusak Studio.

Your work bridges traditional craft, industrial manufacturing, and digital fabrication. What drew you to this hybrid approach, and how do these methods shape your creations?

I tend to not differentiate between these categories, to be honest. I treat these methods as a broad palette of possibilities that I make use of freely. Digital fabrication may be as time- and labour-consuming as traditional crafts, or even more so. With the Ghort Orchid project, for instance, we started by 3D-scanning real orchid flowers, and later elaborated their shapes in the digital environment, which took many hours of actual manual labour, pixel by pixel, bit by bit. After they were 3D printed in a weeks-long process, I manually altered the surface of each sculpture, achieving an intriguing effect that suggests visual decomposition. Once the process is kickstarted, I know exactly what to do and which techniques or methods to apply.

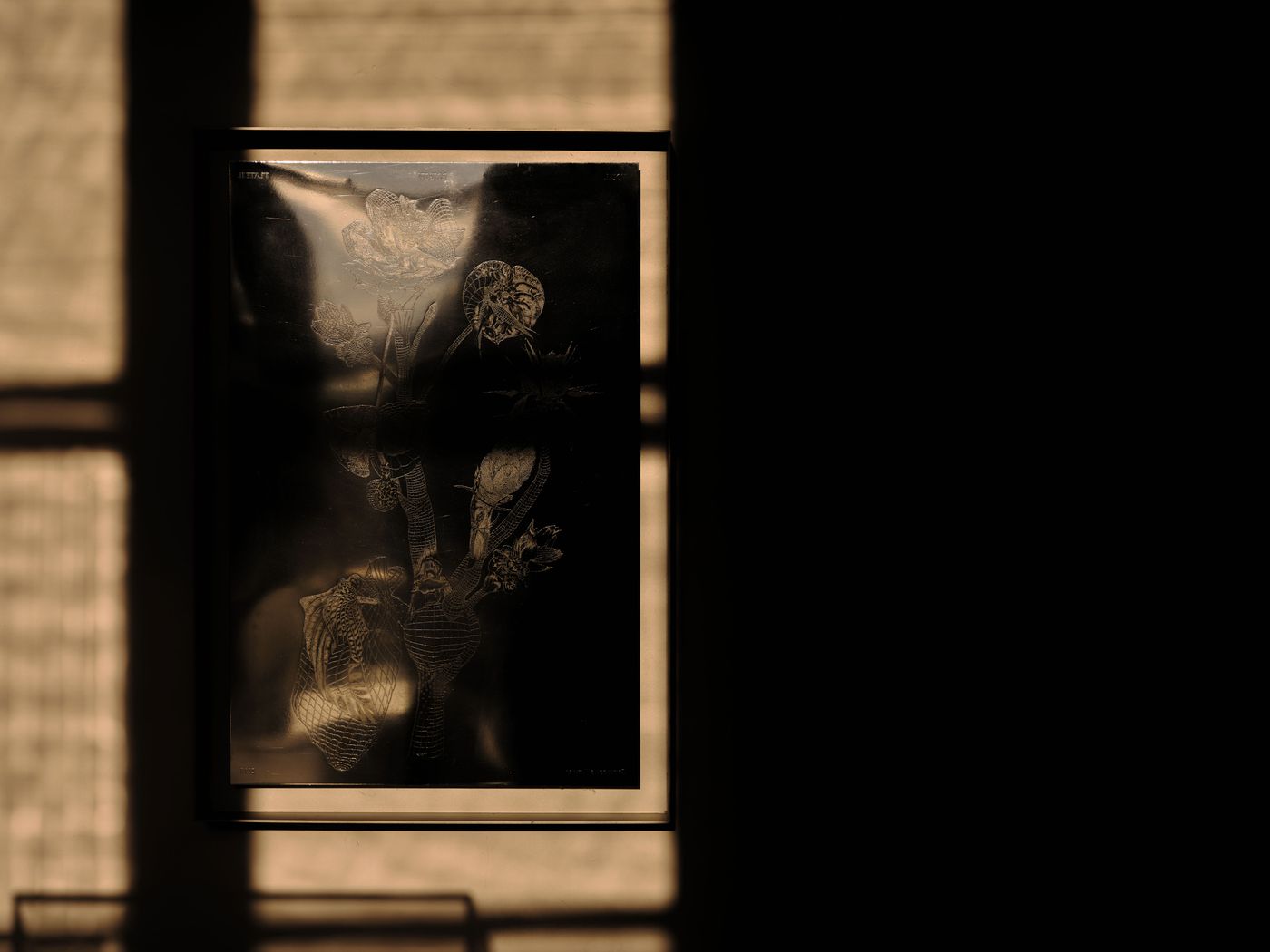

Orchid research. © Marcin Rusak Studio.

Orchid research. © Marcin Rusak Studio.

Swindo Foundation. Photo by Bill Stamatopoulos for Yatzer.

Swindo Foundation. Photo by Bill Stamatopoulos for Yatzer.

Tephra Vase 05. Selected and processed real flowers, steel wire, jute fabric, glass, wood, metal, LED lights. Photo © Marcin Rusak Studio.

In several projects, you upcycle materials like waste flowers and discarded metal as a critique of consumerism. Do you see your work as a form of activism, or is it more about shifting perceptions of value?

It’s definitely about negotiating the perceptions of the value of the things we collect and which arouse a certain kind of emotional attachment. I wouldn’t call it activism; it’s more nuanced and subtle. I am all about opening a conversation rather than preaching and converting others to my worldview.

Walk us through your creative process, from initial concept to finished piece. How much do you plan, and how much do you allow for spontaneity?

Every time I design something new, it begins with my hand sketches or models. And a lot of thinking, dreaming, wandering. Then, there is the 3D modelling, rendering, prototyping and sampling that I work on with my team. The process usually goes from spontaneity and intuition to rigour and deliberate, well-informed choices.

Swindo Foundation. Photo by Ada Zielinska. Courtesy of Marcin Rusak Studio.

What inspired the creation of the Swidno Foundation, and what drew you to the abandoned villa that now serves as its home?

The villa offers a unique environment for me to observe the lifecycle of my works, and how they interact with both historic architecture and overwhelming nature. In a broader perspective, the foundation will allow me to give back to society, bridging the local with the global, art and science, traditional craft and technological innovation. Although we’re not yet established formally yet, Swidno already functions as a meeting place where we invite internationally acclaimed design professionals, collectors and curators to discover Poland through our unique lens.

Swindo Foundation. Photo by Bill Stamatopoulos for Yatzer.

Swindo Foundation. Photo by Bill Stamatopoulos for Yatzer.

Swindo Foundation. Photo by Bill Stamatopoulos for Yatzer.

Swindo Foundation. Photo by Bill Stamatopoulos for Yatzer.

Swindo Foundation. Photo by Bill Stamatopoulos for Yatzer.

Birthday Orchids. Photography © Marcin Rusak Studio.

Birthday Orchids. Photography © Marcin Rusak Studio.

Birthday Orchids. Photography © Marcin Rusak Studio.

After a three-year hiatus, you returned to Milan Design Week with "Ghost Orchid", a new series of light sculptures presented at Alcova Milano. What inspired this project, and what materials and processes did you employ?

The project began as a tribute to my grandfather, who cultivated orchids. In it, I try to inhabit the mindset of a “mad scientist,” replicating the multistep cultivation process through digital means as a way of reconnecting the past with the future. The abstract forms of the sculptures are based on real flowers that we scan in the studio and later manipulate digitally—guided by the same questions I imagine my grandfather might have asked himself: What qualities of the flower am I looking for? Is this the form that I want to bring to life? And if so, which material/means should I use for that?

The first Ghost Orchid sculpture was “planted” last year at Maison Bernard in the south of France, thanks to an invitation from the Genius Loci Foundation. The presentation in Milan, which we staged in collaboration with light director Jacqueline Sobiszewski, engages with the spirit of the place, the Serre di Pasino, a complex of abandoned glasshouses which were once famous for cultivating white orchids.

Installation view, Ghost Orchid by Marcin Rusak at Alcova Milano, Milan Design Week 2025.

Installation view, Ghost Orchid by Marcin Rusak at Alcova Milano, Milan Design Week 2025. The selected greenhouse is nearly identical to the one where Marcin Rusak's grandfather once bred orchids.

This context allowed me to go beyond the act of creating and consider the entire lifecycle of the work. With the help of our partners at Łukasiewicz–IMPiB, a research institute in Poland, we developed a cocktail of microorganisms that enable the sculptures, which are 3D printed using PLA [a recyclable, natural thermoplastic polyester that is derived from renewable resources such as corn starch or sugar cane] to decompose in compost within just a few weeks. It’s not that I want to discredit events like design week—we’re wired to be excited by new things, and that’s perfectly natural. But in a world saturated with stuff, I think it’s worth also thinking about how things end.

Marcin Rusak's grandfather in one of the family's greenhouse. Courtesy of Marcin Rusak.

Installation view, Ghost Orchid by Marcin Rusak at Alcova Milano, Milan Design Week 2025.

Installation view, Ghost Orchid by Marcin Rusak at Alcova Milano, Milan Design Week 2025.

Installation view, Ghost Orchid by Marcin Rusak at Alcova Milano, Milan Design Week 2025.

Installation view, Ghost Orchid by Marcin Rusak at Alcova Milano, Milan Design Week 2025.