David Popa's Ephemeral Earth Murals Offer a Glimpse into the Profound Mysteries of our Existence

Words by Eric David

Location

David Popa's Ephemeral Earth Murals Offer a Glimpse into the Profound Mysteries of our Existence

Words by Eric David

Land artists have always sought unspoilt natural settings for their works; Robert Smithson found his way to the Great Salt Lake in Utah early on in his career, Michael Heizer ended up in the Nevada desert, while Richard Long’s peripatetic practice took him to the Scottish Highlands, Nepal’s forests and India’s tribal lands among other places. Finland-based American artist David Popa takes this practice one step further by creating site-specific earth murals on even more challenging locations such as floating ice sheets in the Baltic Sea and crevasse-ridged glaciers in Norway.

Like most land artists, and prehistoric cave painters, Popa only uses natural pigments found on-site such as charcoal, earth and ground shells, mixed only with source water, which means that his work’s longevity depends on the whims of mother nature—with some works having dissolved in a matter of a few days or months. In fact, their transience is part of what drew the artist to land art in the first place. For Popa, the ephemerality of his painstakingly painted pieces, which he evocatively captures through the eye of a drone, shines a light on the nature of our brief existence and the profound mysteries it holds.Unlike the pioneers of the land art movement though, who purposefully took their work out of traditional art spaces like galleries and museums to underline the commodification of art inspired by the tenets of Minimal and Conceptual Art, Popa’s background in street art attests to a more primal connection with the outdoors.

As he confessed in a recent chat with Yatzer, his fondest childhood memories are intimately connected with nature, which may also explain how the creation of every piece is also a deeply emotional experience. As his friend and videographer Jean-Paul Mannon says, when Popa paints on location, the spray-can becomes part of himself, an extension of his soul. In our conversation below (edited for brevity and clarity), the artist talks about his artistic practice, street art origins and why he left his native New York to move to Finland.

(Answers have been condensed and edited for clarity.)

Lauttasari.

Photography © David Popa

Inceptus.

Photography © David Popa

Tell us a bit about your background. Did you always want to be an artist?

Actually, I didn’t want to become a professional artist. I was good at painting and drawing growing up due to the fact that my father was/is a professional artist in NYC. That exposed me to plenty of art growing up—so much so that I went to a specialised arts high school in NYC and even majored in painting in college—however the lifestyle of sitting in a studio working on a painting all day didn’t appeal to me. I was involved with a lot of sports growing up and knew that I wanted to participate in something more kinetic that allowed a level of exploration. Stumbling onto street art dramatically shifted everything for me.

Your artistic practice was forged through your involvement with street art. How did this phase influence you as an artist?

As mentioned, it changed everything for me. To be more specific, my involvement with street art early on fell along the lines of creating large murals in legal graffiti spots, also called free-walls. When you paint at such a location your work can be painted over at any time, so there’s a rush to finish a large-scale piece in a day or two and then document it with photos and videos, a process that became addicting.

Power of the Earth.

Photography © David Popa

Le Pouvoir De La Terre

Cinematographer, Director- Nathan Popa- popacreative.com/about

Editor, Artist- David Popa- davidpopaart.com

Head Winemaker at Cantenac Brown- José Sanfins

Power of the Earth.

Photography © David Popa

Power of the Earth.

Photography © David Popa

What drew you to land art? What inspired you to begin using the natural landscape as your canvas and natural pigments as your medium?

It was a rather slow evolution over a period of around six years before I fully committed to ephemeral land art works in nature. A key part of my childhood was escaping the city nearly every weekend with my family to a nature reserve on Long Island where almost all of my fondest memories took place. As I got older, my desire to merge nature into my work only grew. On a trip with my wife to the Lofoten Islands in Norway, all I could think about was how I could go about creating a work of art straight onto the mountainside. To make it happen I ended up looking both backwards and forwards—in essence I appropriated the medium of early cave painters. By using natural pigments from the earth like chalk, ochres and charcoal mixed with water, the work became ephemeral due to the lack of a binding agent. Instead of another painter covering up my work as was the case in my street art days, now nature would have the last say.

With what criteria do you select the locations for your work? How difficult is it to pinpoint the exact spot? What factors do you take into account?

I mainly look at locations with incredible textures where it seems that some kind of latent life is calling out to be revealed. I never know exactly what I’m going to create at a specific location and I can alter the location at any time if I don’t feel emotionally compelled to it. I also look for locations that look like they have the possibility of something unexpected occurring.

Do more challenging conditions such as remoteness, poor accessibility and harsh weather make a place more thrilling to engage with? Was the glacier in Norway the most challenging location so far?

You said it. It’s as much about the thrill of exploration and adventure as it is about the final work. My most recent piece on a glacier in Norway was certainly very challenging, from how remote the spot was, to the dangerous crevasses and the small window of time to pull it off (4 hours). This was also the case with my recent series on ice floes which can float away or crack in a matter of a few hours.

Born of Nature II.

Photography © David Popa

Redemption.

Photography © David Popa

Fractured- Short Film

Shot and edited by David Popa with camera help from Samuel Putkonen.

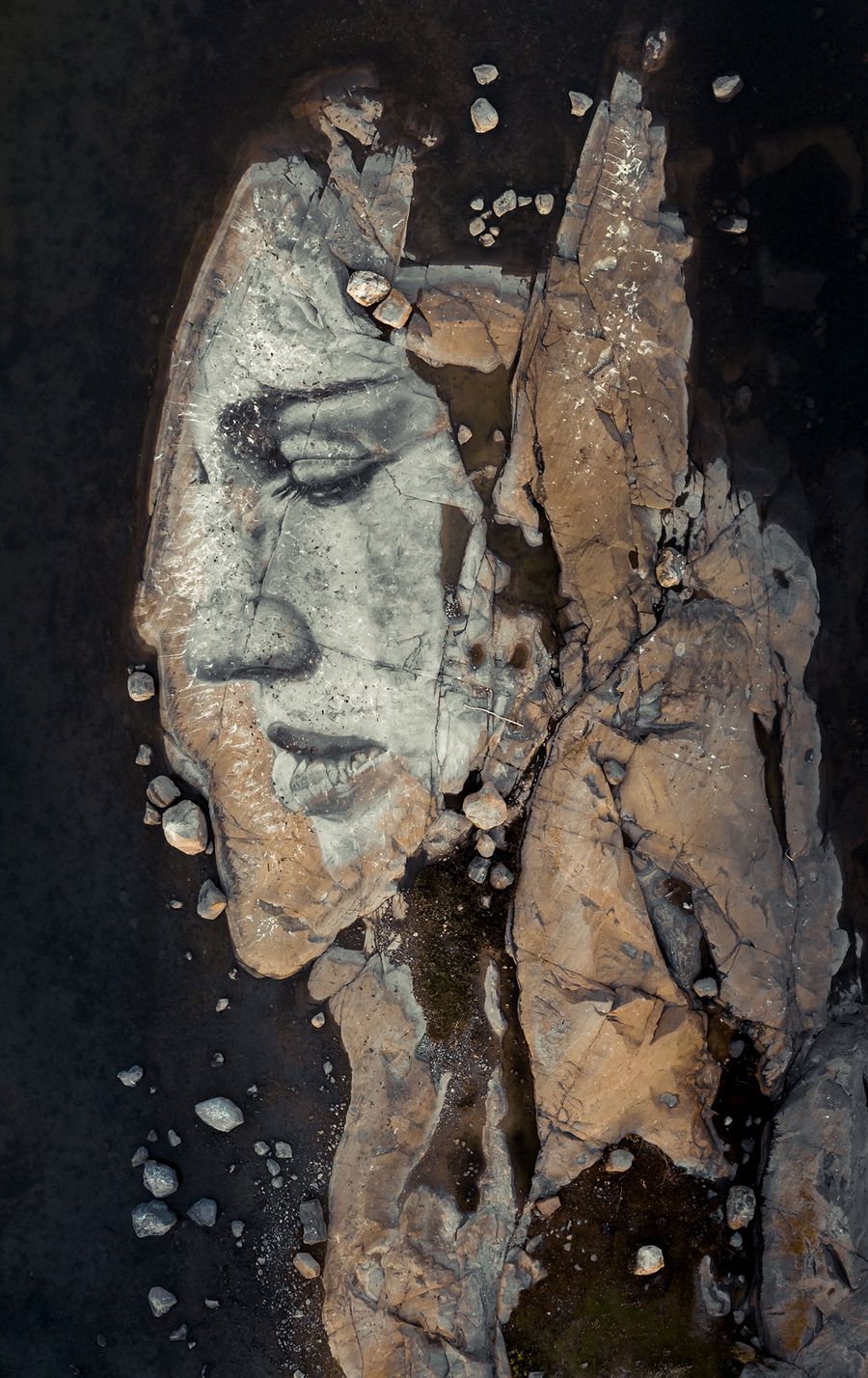

Fragment 1. From the Fractured series.

Photography © David Popa

Fragment 2. From the Fractured series.

Photography © David Popa

Talk us through your creative process. How much preparation is required for each project? Do you plan everything ahead or is there also room for spontaneity?

The first step is always scouting for an amazing location. I fly my drone and take photographs of potential spots and then use the images, right there on site, in combination with various photographs from image banks using an app on my phone to see how various subjects fit with the location. It could be a portrait, an animal or even an image of my new-born daughter, it really varies. At this stage I feel like I’m an archaeologist unearthing something buried long ago. In the end, I follow my gut—often the real reason I chose the subject is revealed to me later—getting to work when the “photoshopped sketch” elicits a deep emotional reaction. I either use the existing landscape textures to guide me regarding the proportions or I make marks on the surface and re-photograph the location in order to use the marks as reference points.

Although every piece is well documented, their inherent ephemerality imbues your land murals with a mystical sensibility, especially since their eventual effacement is part of a natural process. How important is this aspect of your work?

This is perhaps the prime theme in my work. We live in an ephemeral world. The transience of our lived existence is possibly the greatest mystery. These larger themes however were unbeknown to me when I first began; I became aware of them later on when working on location. The beauty of the raw natural materials, the animals and huge expansive spaces that surround me often make me cry—it’s in these moments that I realise there is so much more to our existence than mere survival and preservation. It’s as if our hearts were meant for much more, for eternity.

Is it a bittersweet feeling to know that the outcome of your hard work is going to eventually fade away? Have there been a case where you had wished the piece was permanent?

Funnily enough I got over this feeling early on when doing street art. My first few works were painted over rather quickly by other artists and I was heartbroken. I thought I might have offended the graffiti writer in some way. After I realised it’s just part of the street art world, I came to love the ephemerality of the work and the fact that only my video and photos remained.

Fragment 4. From the Fractured series.

Photography © David Popa

Fragment 3. From the Fractured series.

Photography © David Popa

The whale-like figure in “Adrift” brings to mind the biblical tale of Jonah and thoughts about the elusive quest for meaning and (self) fulfilment. How personal was this project for you?

Yes, the theme of the story on Jonah was at the forefront of my mind and how relevant it is to so many of us today. If we don’t follow who we are meant to be the inevitable result is to end up “Adrift” and ultimately swallowed. However, the subject was primarily inspired by the location—it was another one of those very mysterious experiences.Being in the presence of such a beautiful yet dangerous force of nature made me feel so insignificant yet so blessed for being able to be present to witness it. We hadn’t seen anyone for days during the expedition, barely an insect. As I walked to the glacier I just started to repeat in my mind, I am adrift, I am adrift.. I was then overcome with a very strong wave of emotions that I can’t link to any specific experience or personal event. It became clear that a figure swallowed by a whale was the subject of the piece. Unfortunately, I didn’t have the time to paint the figure within the whale so I spontaneously laid down on the glacier “within the belly of the whale”.

Adrift.

Photography © David Popa

Prometheus.

Photography © David Popa

Eagle's Eyes.

Photography © David Popa

You are a born and bred New Yorker currently living in Finland. What made you decide to move to Europe? Is Finland’s diverse natural landscapes part of the reason?

I actually moved to Finland for love! I visited during the summer of my junior year in college to build up my street art portfolio as there are plenty of walls to legally paint murals on in Helsinki. I ended up falling in love with a Finnish girl and the next year I moved there and proposed. I have lived here my entire adult life and have 2 kids (third on the way)!

What are you working on right now?

I hope to create another series on the ice this winter and perhaps create my first desert series.

What is your dream location to create an earth mural?

The moon.

Exodus.

Photography © David Popa