Brutalist Plants: A Photography Book Showcases the Wondrous Fusion of Brutalist Architecture and Nature

Words by Yatzer

Location

Brutalist Plants: A Photography Book Showcases the Wondrous Fusion of Brutalist Architecture and Nature

Words by Yatzer

Brutalist architecture is known for its cold and austere aesthetic, but what happens when the harshness of raw concrete meets the softness of green foliage? This is the fascinating subject of “Brutalist Plants”, a new photobook by Instagrammer Olivia Broome that showcases a curated selection of over 150 images of Brutalist structures flirting with nature, sourced from hundreds of professional and emerging photographers around the world. Released by Hoxton Mini Press, the book is based on Broome’s Instagram account of the same name which, since its launch in 2018, has grown into a vibrant community of ‘Brutalist plant’ enthusiasts. From iconic buildings like the Barbican Centre in London and its Babylonian-style cascading courtyard gardens, to war memorials in the former Soviet and Yugoslavian states, to forest cabins in Mexico, Broome's book takes readers on a sweeping journey across various epochs and locales, highlighting the curious and oft-overlooked intersection between nature and Brutalist architecture.

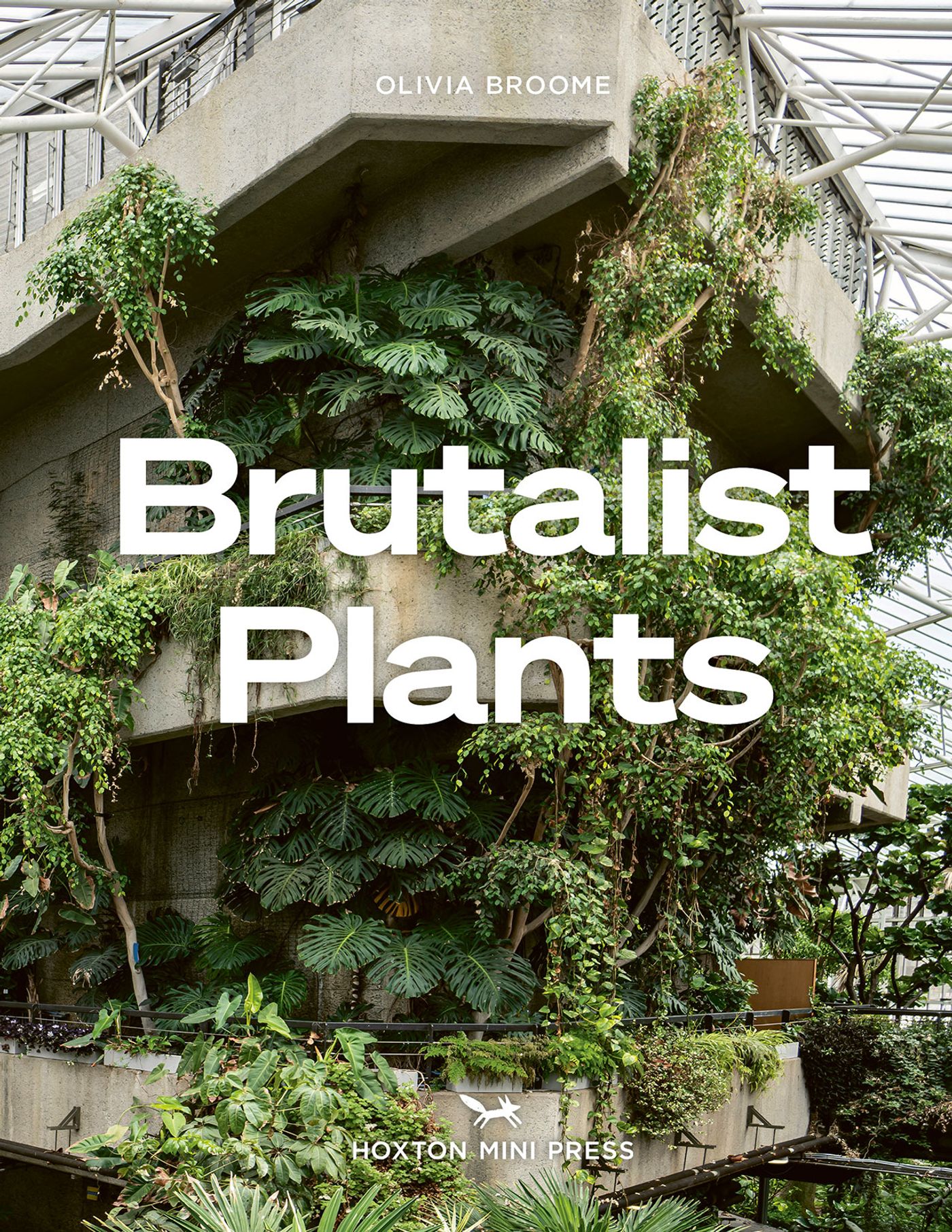

Book Cover. Brutalist Plants by Olivia Broome. Cover photo by Architectonic Travels UK. Published by Hoxton Mini Press.

Les Étoiles d’Ivry, Paris, France.Architect: Jean Renaudie Photo © pp1 / Shuterstock

Growing up in Switzerland, a country with a rich Brutalist legacy, Broome developed a deep fascination with this architectural style. The term Brutalism originates from the French phrase béton brut, translating to 'raw concrete.' Coined by Le Corbusier to describe his revolutionary Unité d'Habitation in Marseille, France, the term gained wider recognition in 1955 when architectural historian Reyner Banham applied it to the British Brutalist movement. Emerging as a stark departure from the ornate architectural trends preceding it, Brutalism symbolized a vision of radical urban renewal in post-World War II Europe. By the 1960s and 1970s, its influence had spread beyond Europe to warmer regions, particularly Latin America.

While it fell out of fashion in later years, Brutalism has experienced a resurgence of admiration from a new generation using social media. This revival transcends mere aesthetics, fuelled by environmental consciousness and a desire to repurpose and adapt heritage structures, as evidenced by the viral hashtag #ecobrutalism. For Broome, the intervention of nature carries both ecological and existential messages: it serves as a reminder of our planet's fragility and transience, as even the most imposing concrete edifices can be eroded by encroaching vegetation.

UNTITLED, 2013. Reinforced concrete, 7 trees. La Vallée, Basse-Normandie, France.Artwork by Karsten Födinger.

Monument to the Revolution, Kozara National Park, Prijedor, Bosnia and Herzegovina.Architect: Dušan DžamonjaPhoto © Alexey Bokov - Balkan Stories.

Mailman Center for Child Development, University of Miami, Miami, FL, United States.Architect: Hilario CandelaPhoto © Felix Torkar.

Reinforced hillside, Aogashima, Tokyo, Japan.Photo © Yasushi Okano.

The Barbican Conservatory, London, United Kingdom.Architect: Chamberlin, Powell and BonPhoto: © Taran Wilkhu

From residential complexes and private dwellings, to theatres, libraries and churches, to water towers and electricity pylons, Brutalist structures demand attention, yet unlike their contemporary counterparts, they do so with an understated dignity and steadfastness. As Broome eloquently notes, they are "loyal, unwavering, stoic: the ultimate shelter." While their stern monumentality may evoke dystopian sentiments, their symbiotic relationship with nature offers a more optimistic perspective: humanity can coexist harmoniously with the natural world if afforded the opportunity for mutual adaptation.

The abandoned Haludovo Palace Hotel, Krk Island, Croatia.Architect: Boris MagašPhoto: © Maciek Leszczelowski.