BRILLIANT BEIRUT - A Chronological Journey Through Lebanon's Capital from the 50’s till today curated by Rana Salam

Words by Costas Voyatzis

Location

Dubai, United Arab Emirates

BRILLIANT BEIRUT - A Chronological Journey Through Lebanon's Capital from the 50’s till today curated by Rana Salam

Words by Costas Voyatzis

Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Location

The first edition of Dubai Design Week was also the springboard for ICONIC CITIES, a new series of annual exhibitions that explore the culture and design scene of the Middle East's urban centres. The exhibition, which was housed in one of the brand new Dubai Design District’s buildings from the 26th to the 31st of October, was dedicated to “the Paris of the East”, namely Lebanon’s capital, Beirut. Designed and curated by designer Rana Salam, the BRILLIANT BEIRUT exhibition explored the impact of local urban dynamics in architecture and the fields of interior, graphic and product design, while touching upon present-day design education and the processes of creating cultural trends in the region.

The Carlton Hotel in Beirut, built by Polish architect Karol Schayer in 1957.

The Spinneys Center in Beirut, built by Polish architect Karol Schayer, 1975.

Organised as a chronological journey, the exhibition was a showcase of the city’s most prominent design and architecture achievements, illustrating all the important milestones of the city’s design history. The visitor's journey (which was staged as a series of long boulevard-like corridors) began in the flourishing 1950s, when the Hotel Carlton (1957) and the Pan-American Building (1953) rose to dominate Beirut’s skyline and the Cinema al-Hamra was constructed on Hamra Street (1958); also the same time when Lebanon’s first group of architects such as George Rais, Assem Salam, Khalil Khoury and Karol Schayer emerged. Moving forward to the maturing era of the 1960s, which came hand-in-hand with an economic boom and the formation of new companies, the first “starchitects” such as the Finnish Alvar Aalto and Polish Karol Schayer arrived in the city.

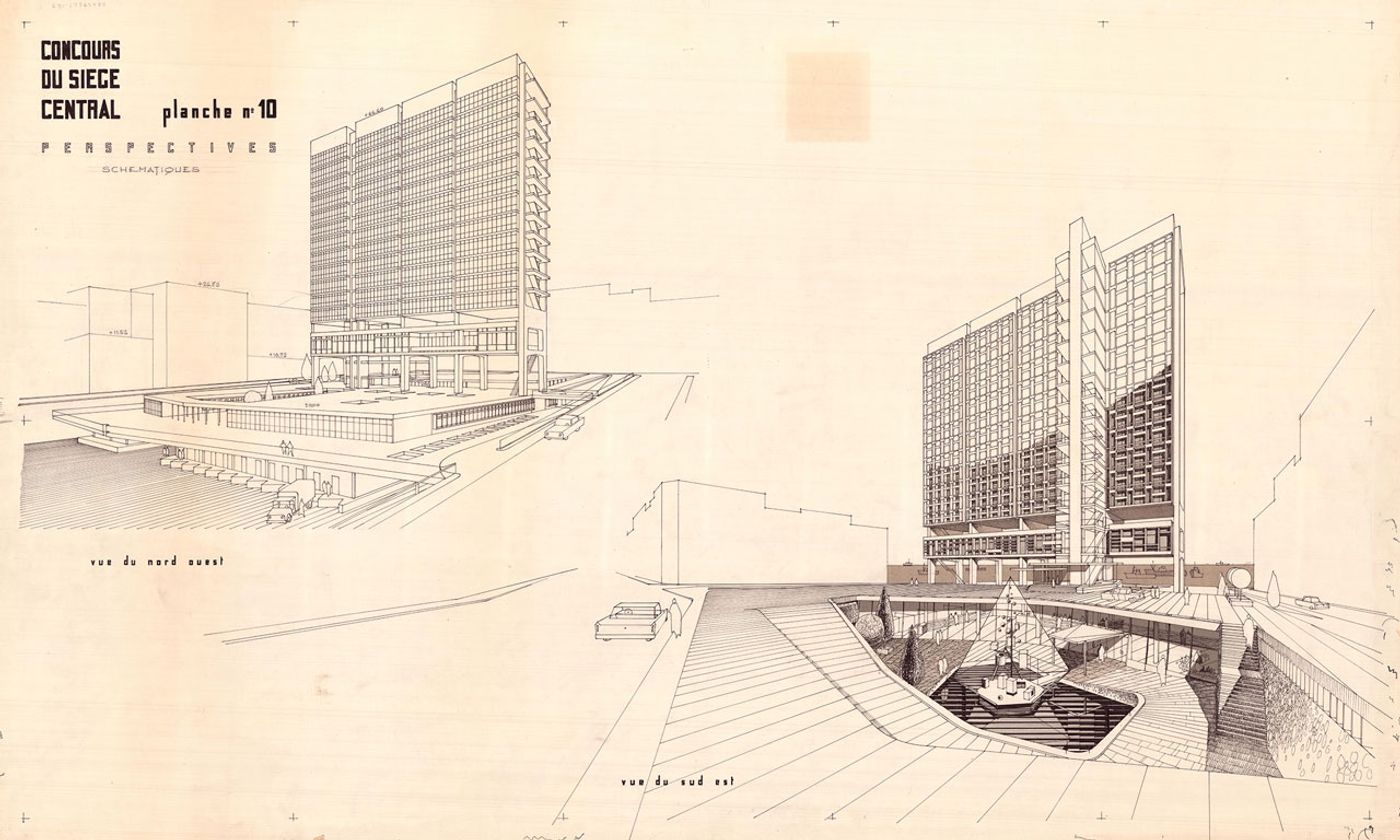

Électricité du Liban Headquarters, by J. Aractingi, J. Nasser, P. Neema and J.N. Conan (CETA), Beirut, Lebanon, 1965-1972. © Arab Center for Architecture, Pierre Neema Collection.

The year 1967 marking the Arab-Israeli war which shook the entire Arab world led to many designers in Lebanon and across the region shifting towards a more pronounced articulation of a distinct Arab modernity in response to the Arabs’ defeat in the war. Assem Salam and Pierre Khoury for example attempted to form a Lebanese-Arab modern architectural language through their construction of religious buildings: Salam’s mosque and Khoury’s cathedral both served as models of a regional modern architectural style. In 1975, with the eruption of the devastating Lebanese civil war followed by fifteen long years of conflict; however, design activity continued. As Zeina Maasri notes: “during the 15 years of civil war, political posters filled the streets and charged the walls of cities all over Lebanon. As the ongoing war formed an intrinsic aspect of everyday life in Lebanon, the graphic signs and political rhetoric of posters became a prevalent sight that shaped the cityscape.”

Liwan, Copper Bowl, Product Design, 1980.

KOUJAK-JABER by Victor Bisharat, 1964. Photo by Serge Najjar, 2013, © Galerie Tanit Beirut.

When I started taking photographs, creation came instinctively and architecture imposed itself on me because of how rich the field is. It became the best possible playground for a ‘lines and shadows’ amateur like me. I am not necessarily about grand architecture. I found that what people consider as boring places or common spaces were not as boring as they said. As a result, I was interested in showing how thin was the line between art, architecture and reality. - Serge Najjar Photographer

Gandour Logo evolution from left to right: 1857, 1940, 1980 and 2014 {designed by Mash Creative & SocioDesign}. Established in 1857 “Gandour is one of the largest confectioners in the Middle East delivering quality food products to satisfied consumer for over 150 years.” They produce gums and candies, chocolates, wafers, cakes, biscuits, and snacks.

Political Posters of the Lebanese Civil War

by Zeina Maasri, 1980.

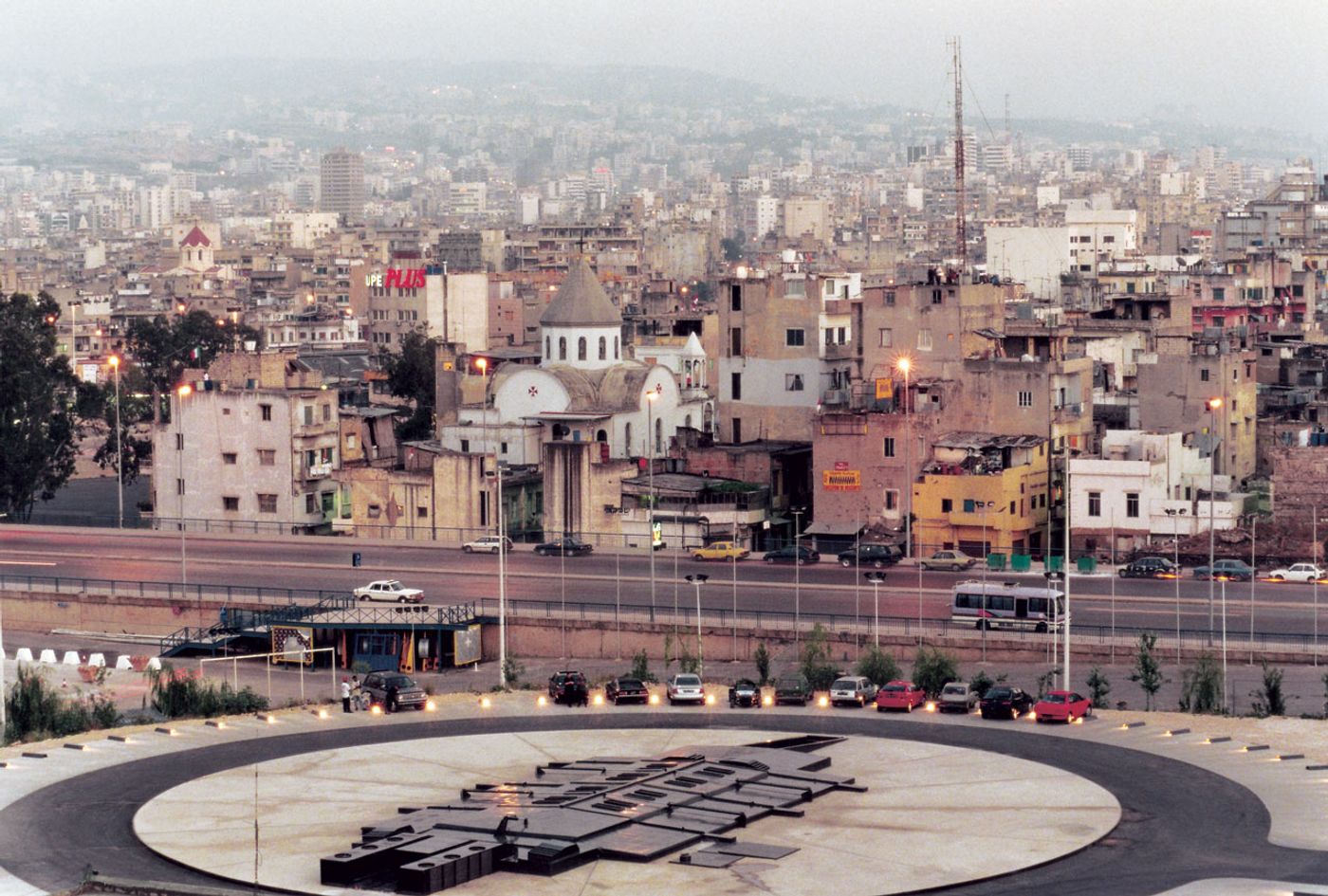

In the 1990s, the country’s rebuilding process recommenced; an era during which Lebanese architect Bernard Khoury designed the famous nightclub B018, considered as one of Beirut’s most important contributions to international architecture in the post-war era: the venue is built underground and has an articulated roof structure made of heavy metal slabs which retracts hydraulically to expose the club’s interior that “bring it to life” in the late hours of the night. In 2000, although the project for the reconstruction of downtown Beirut initiated by Solidere was met with controversy, nevertheless Lebanon was gradually returning to its pre-war state. Today, and despite new and overwhelming political and social problems, the city's evolution continues with remarkable examples of architecture and interior design, such as: the famous Lebanese restaurant LIZA, owned by Liza Soghayar, the Aïshti Foundation building designed by British architect David Adjaye, and the Issam Fares Institute at the American University of Beirut designed by Zaha Hadid Architects. More recently, the architecture practice of Wilmotte & Associés in collaboration with local architect Jacques Aboukhaled has produced a remarkable revival of the Sursock Museum, which reopened last month.

B018 nightclub by Bernard Khoury, 1998. Photo © DW5 Bernard Khoury.

B018 nightclub by Bernard Khoury, 1998. Photo by Ieva Saudargaite © DW5 Bernard Khoury.

B018 nightclub by Bernard Khoury, 1998. Photo by Ieva Saudargaite © DW5 Bernard Khoury.

I resist the notion of condensing the essence of any city into an image, a sound, a smell, a taste… and I will certainly not venture into depicting Beirut through consensual and reductive representations of any form. However, I can say that my dear city is certainly not the prettiest – she is loud, she can smell pretty bad in some areas, but I certainly like my acquired taste of her. - Bernard Khoury

B018 nightclub by Bernard Khoury, 1998. Photo by Ieva Saudargaite © DW5 Bernard Khoury.

B018 nightclub by Bernard Khoury, 1998. Photo by Ieva Saudargaite © DW5 Bernard Khoury.

AUB IOEC ENGINEERING LAB by Nabil Gholam Architects. Photo © Ieva Saudargaitė.

The refurbishment and the extension of the Sursock Museum, designed by French design practice Wilmotte & Associés and Libanese architect Jacques Aboukhaled. Photo © Wilmotte & Associés / Jacques Aboukhaled.

Brand Identity for Falafel Aboulziz by Wondereight.

Starch is a non-profit organization that helps launch Lebanese emerging designers. Designed by Ghaith Abi Ghanem & Jad Melki / Ghaith&Jad.

STARCH by GHAITH&JAD. Video by Christian Moussa.

Beirut is borderline. I look at Beirut and I see inherent demarcation lines and uncertain boundaries; geographical, political, religious and social. But then I look at Beirut again, my city, my line, my border and I have this ecstatic feeling that somehow everything is possible, all lines could be distorted, all borders could be cracked but I’m gonna have to fight for it. Hard. - Karine Fakhry, Principal Architect, FaR Architects

Lebanese architect's Karim Bekdache showrrom, specializing in custom made projects as well as selling vintage furniture from the 50's , 60's and 70's.

LISA restaurant in Beirut, photo © LISA Beirut.

"Camille" cake stand by Marc Dibeh. Hardcut Brass | French Oak | Maple | 29 × 49 cm | 2014. Photo © Art Factum Gallery Beirut.

A coffee-table from the LOULOU/HODA series of products by david/nicolas for Art Factum Gallery Beirut. The collection is inspired by the furniture of the designers' grandmothers’ houses.

Arthropod lamp by Ghassan Salameh, 2015.

Why Beirut is brilliant? Because Beirut does not imitate other cities. Beirut is not a replica. It is a special combination of people, lifestyles and architecture that result in an authentic city with a unique modern identity. Beirut is convinced it can be to be the most advanced, trendy and cutting edge city. Without copying any other city. Because Beirut is ambitious. Too ambitious sometimes. Even arrogant. Because many people in Beirut decided to live here after trying London, Paris or New York. Because Beirut is always moving forward. To forget the past that is full of wars. Because Beirut has been wounded so many times that it lives every day like if it was her last. - Karim Bekdache. Architect, Karim Bekdache Architects

Installation view. Brilliant Beirut, photo © Dubai Design Week 2015.

RED CHAIR by Lebanon's most prominent modernist architects Assem Salam (1955). Brilliant Beirut exhibition, photo © Dubai Design Week.

Curator Rana Salam’s love for her birthplace is evident on the panels of the exhibition’s corridors, since even me -someone who has not visited this city yet! - had the impression of walking through its streets, all the while exploring its design evolution and tracing its development from the nation’s independence in the 1950s to the present day. Brilliant indeed! Although the exhibition is now sadly over, we hope that its well-curated chronological journey will be published as a coffee-table book in the near future.

Assem Salam, the renowned Lebanese modernist architect and father of Brilliant Beirut’s curator Rana Salam, bought her a scooter as a gift when she was 15 years old, thus giving her the opportunity to explore her city in a way that was to prove to be powerful enough to shape her personality and aesthetics - in turn, forming the Middle-Eastern pop-culture signature style that she has today. With no facility for formal design education in Lebanon, she left Beirut in 1986 to pursue her BA at Central St. Martins, followed by an MA from the Royal College of Art. Soon afterwards, in 2002, she opened her first studio in London before relocating to Beirut eight years later in 2011 and establishing the Rana Salam Design store, featuring her own line of products, including a home collection and accessories, as well as fine art, prints and one-of-a-kind objects (all also available through her online store). Throughout her career, Rana Salam has produced distinctive designs for clients as diverse as Harvey Nichols, Villa Moda, Liberty of London, Boutique 1, the Victoria & Albert Museum and Paul Smith.

BRILLIANT BEIRUT - An exhibition Designed and Curated for Dubai Design Week 2015 by Rana Salam.

Brilliant Beirut's curator Rana Salam. Photo © Dubai Design Week 2015.