Tatoueurs, Tatoués: The Biggest Tattoo Art Exhibition In The World

Words by Rooksana Hossenally

Location

Paris, France

Tatoueurs, Tatoués: The Biggest Tattoo Art Exhibition In The World

Words by Rooksana Hossenally

Paris, France

Paris, France

Location

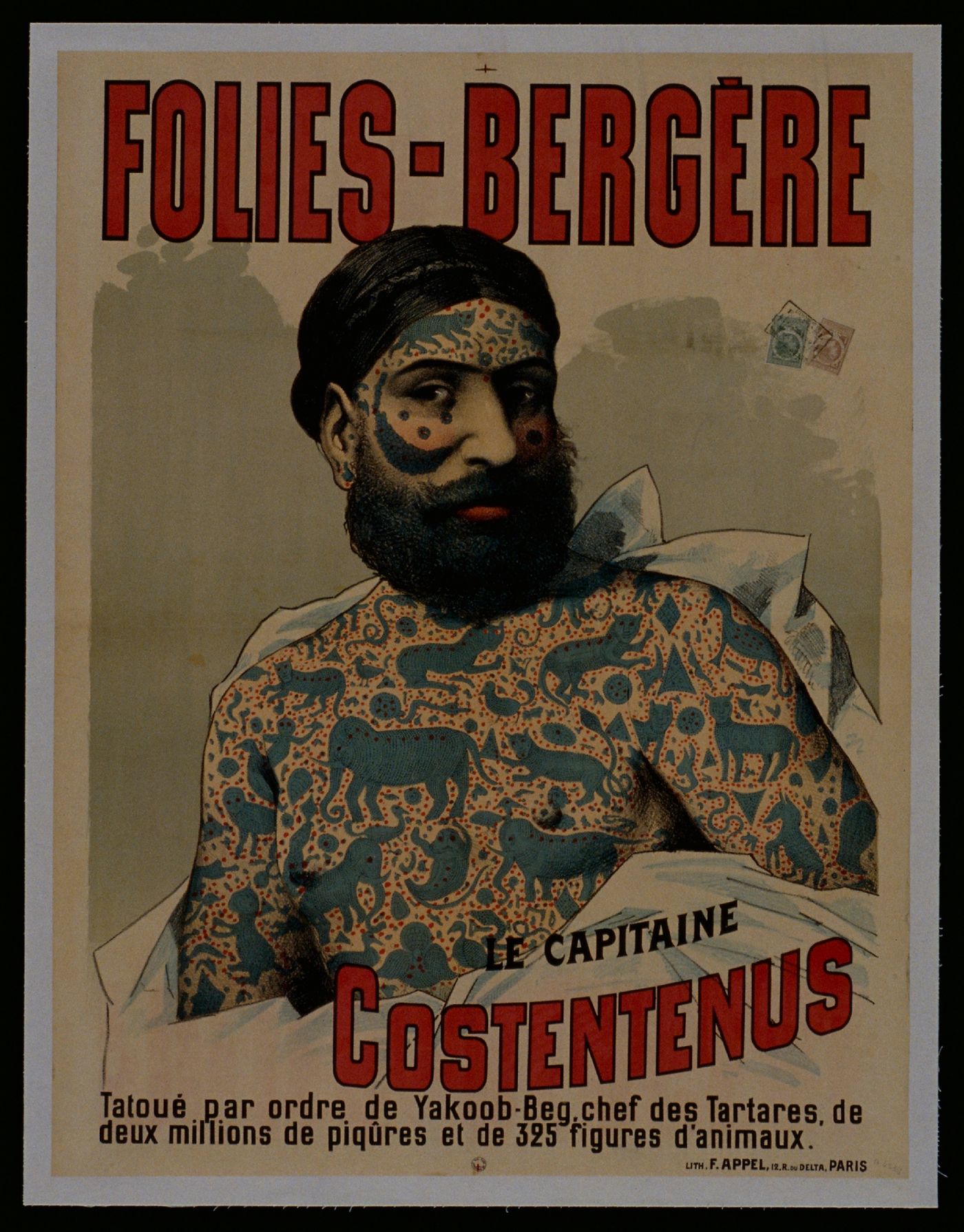

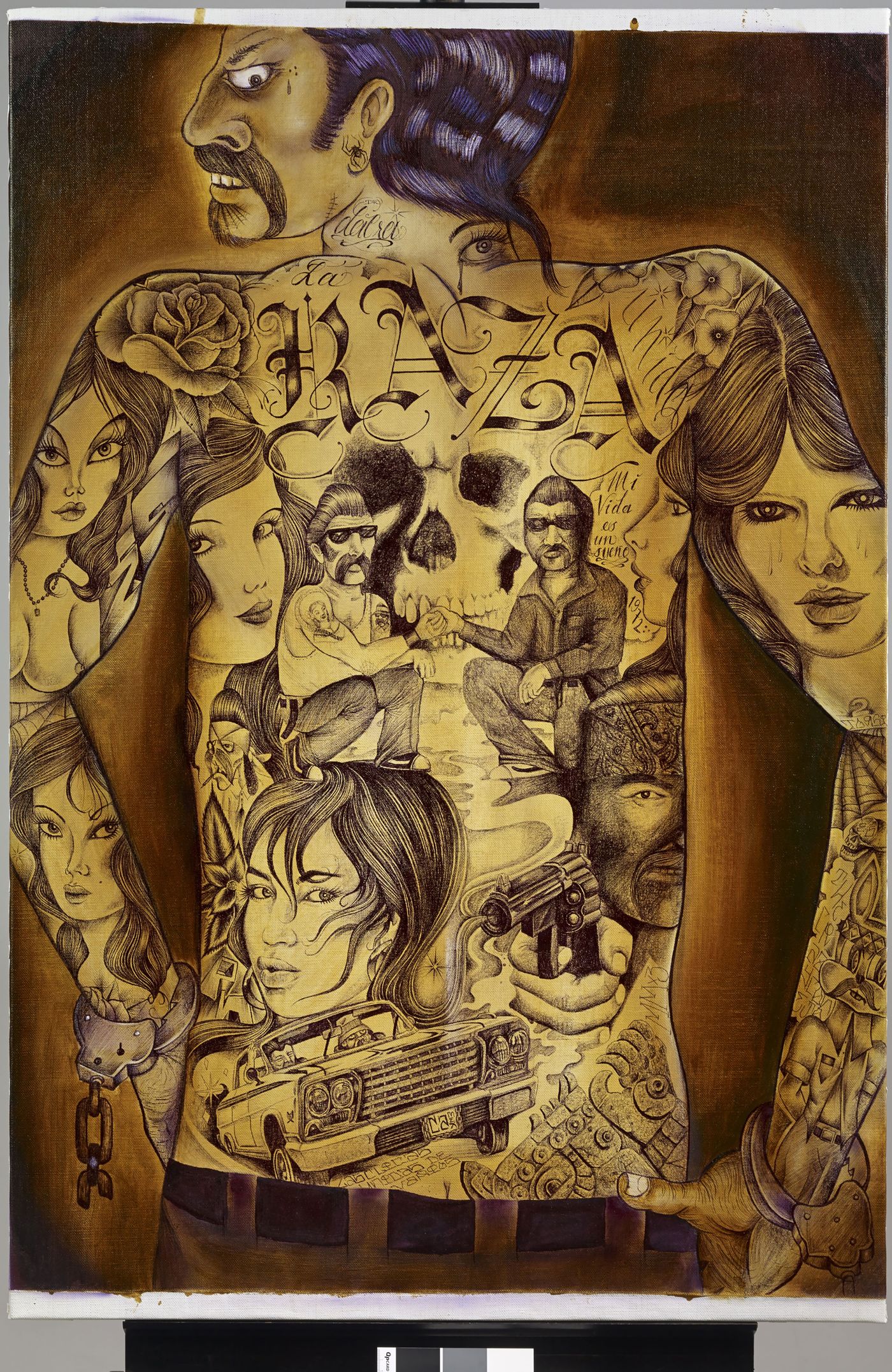

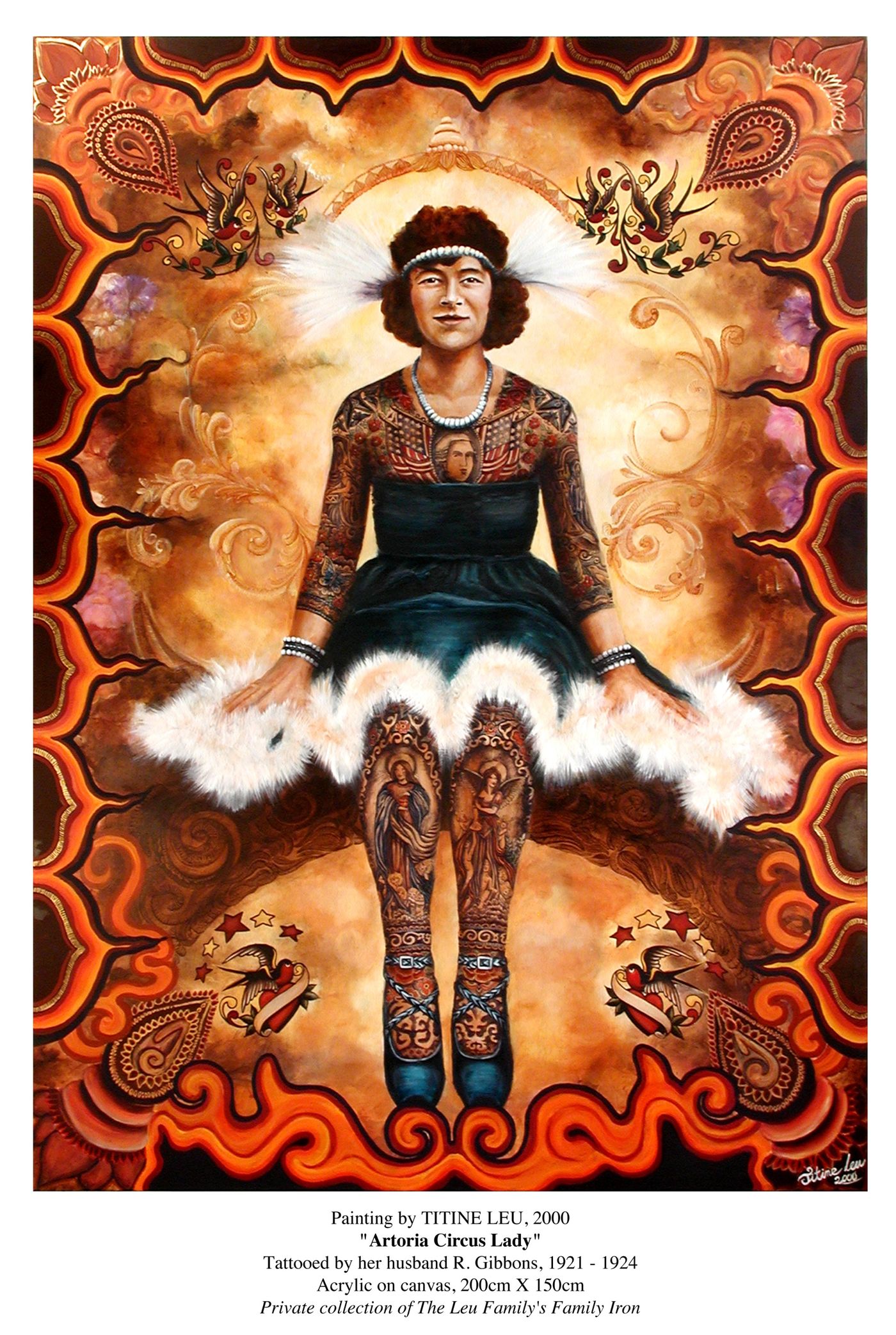

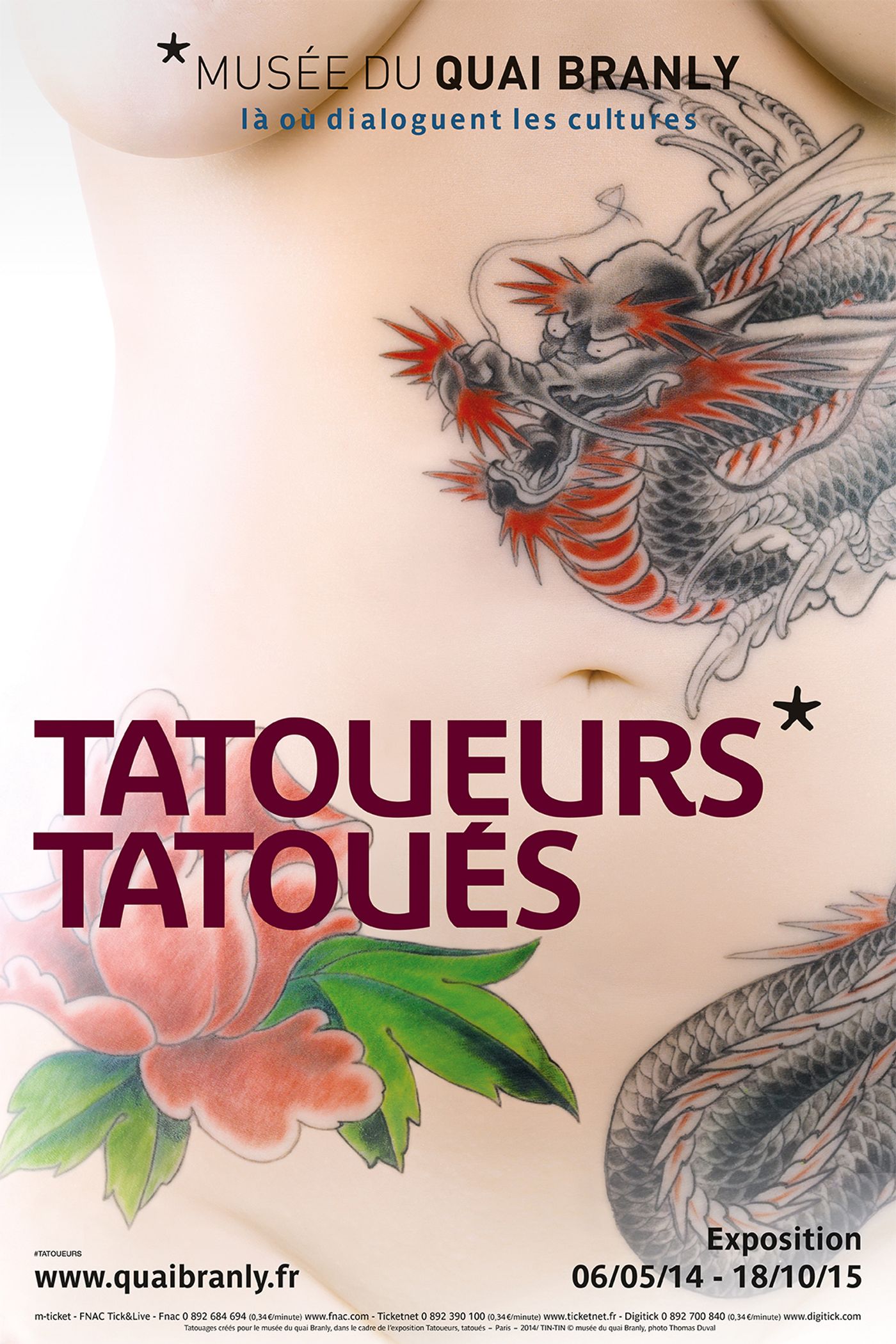

Tattoo art hasn’t always been so cosmopolitan, nor has it been viewed as an art form. That is, until very recently. Curated by Anne and Julien, editors of ‘outsider’ art magazine Hey!, well-known French tattooist Tin-Tin, and experts in their field, Pascal Bagot and Sébastien Galliot, the exhibition ''Tatoueurs, Tatoués'' (tattooists, tattooed) traces the history of the tattoo from the 18th century to the present-day. Set to begin on 6th May at the Quai Branly Museum in Paris, the exhibition will comprise some 300 works making it one of the most significant tattoo shows in the world and will feature tattoo art from around the world spanning Japan to Europe.

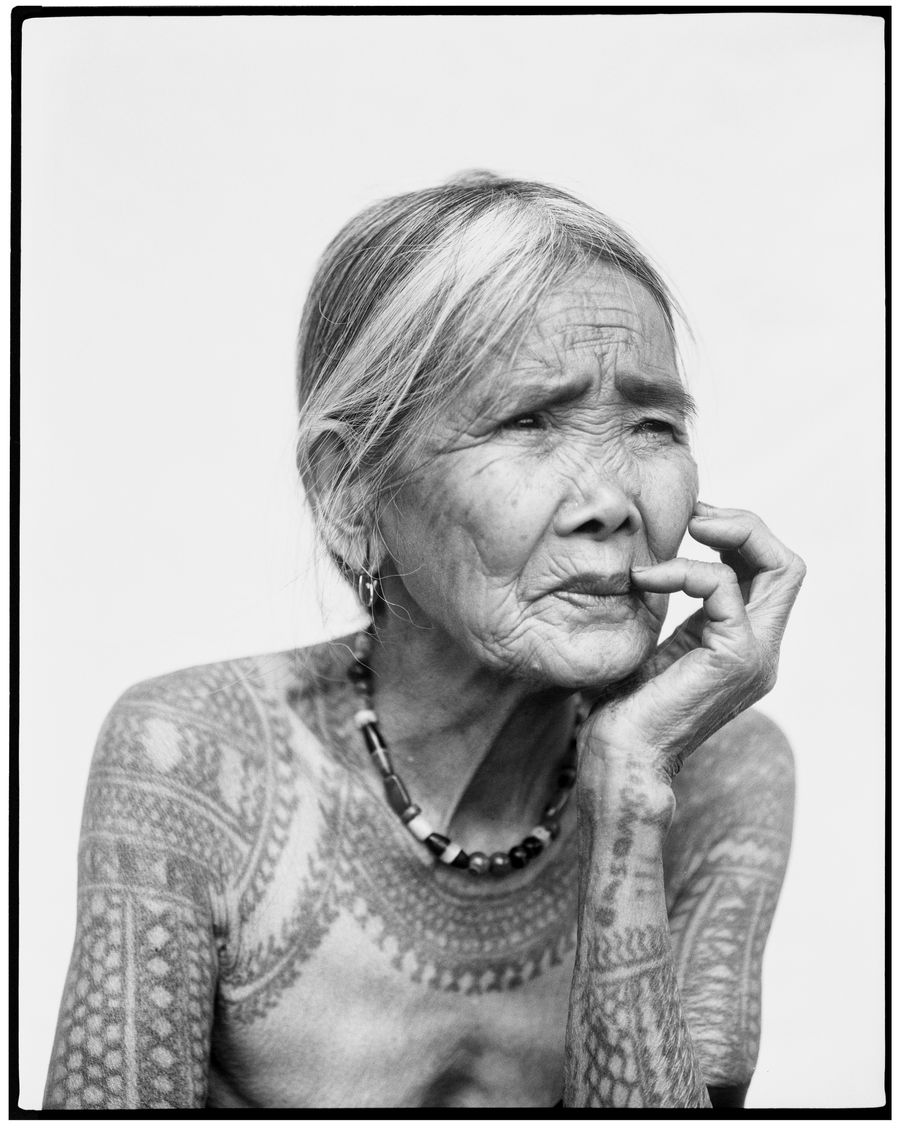

The last tattooed Kalinga woman, Philippines, 2011. © Jake Verzosa, artist’s private collection.

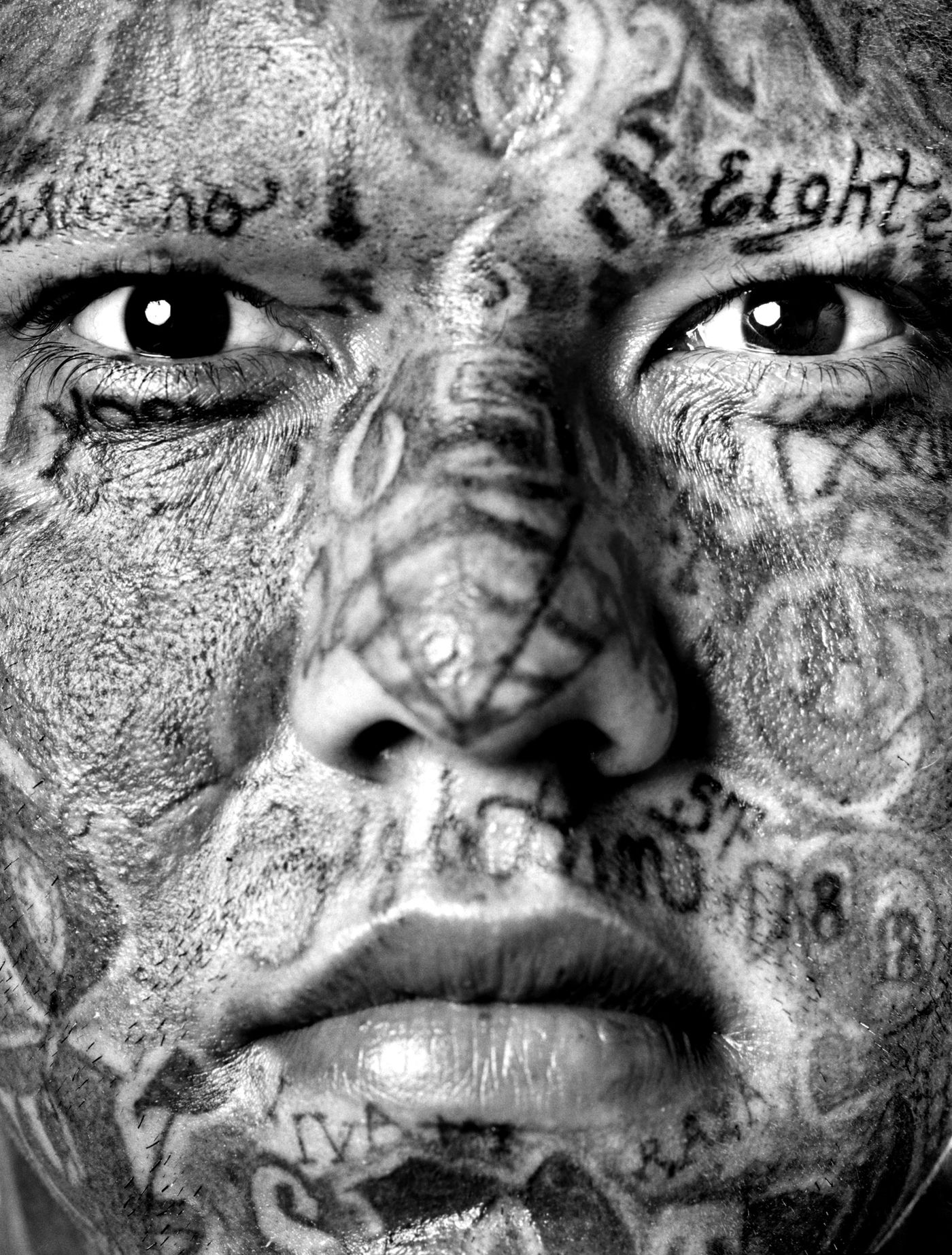

Maras portrait, 2006 © Serie Maras, 2006. Isabel Muñoz.

Pascal Bagot, journalist, film director and curator of the Japan section for the Tatoueurs, Tatoués exhibition, talked to Yatzer about this first major homage to tattoo art and the significance of Japanese tattoo as an art form.

Sitting in a dark corner of a wood panelled bar close to République in central Paris, wearing a woolly navy hat and a distressed denim jacket, the heavily bearded Pascal Bagot looks up as I approach the polished mahogany table. His blue eyes smile from behind a pair of half-rimmed glasses before he offers an assertive handshake. Born in Toulouse and having lived in Paris for 16 years, the 36-year-old’s passion for Asian tattoo art began when he first came across the work of Paris-born tattooist Filip Leu in the French tattoo publication Tatouage Magazine. ''I was immersed in metal music and tattoo art was something I was already familiar with, but it wasn’t until I saw Leu’s dragon on a woman’s arm that something clicked. When I saw the images of Tokyo-based master tattooist Horitoshi I’s work, I decided I wanted to be tattooed.''

Traditional Japanese tattoo © Photo: Tatttooinjapan.com / Martin Hladik.

Traditional Japanese tattoo © Photo: Tatttooinjapan.com / Martin Hladik.

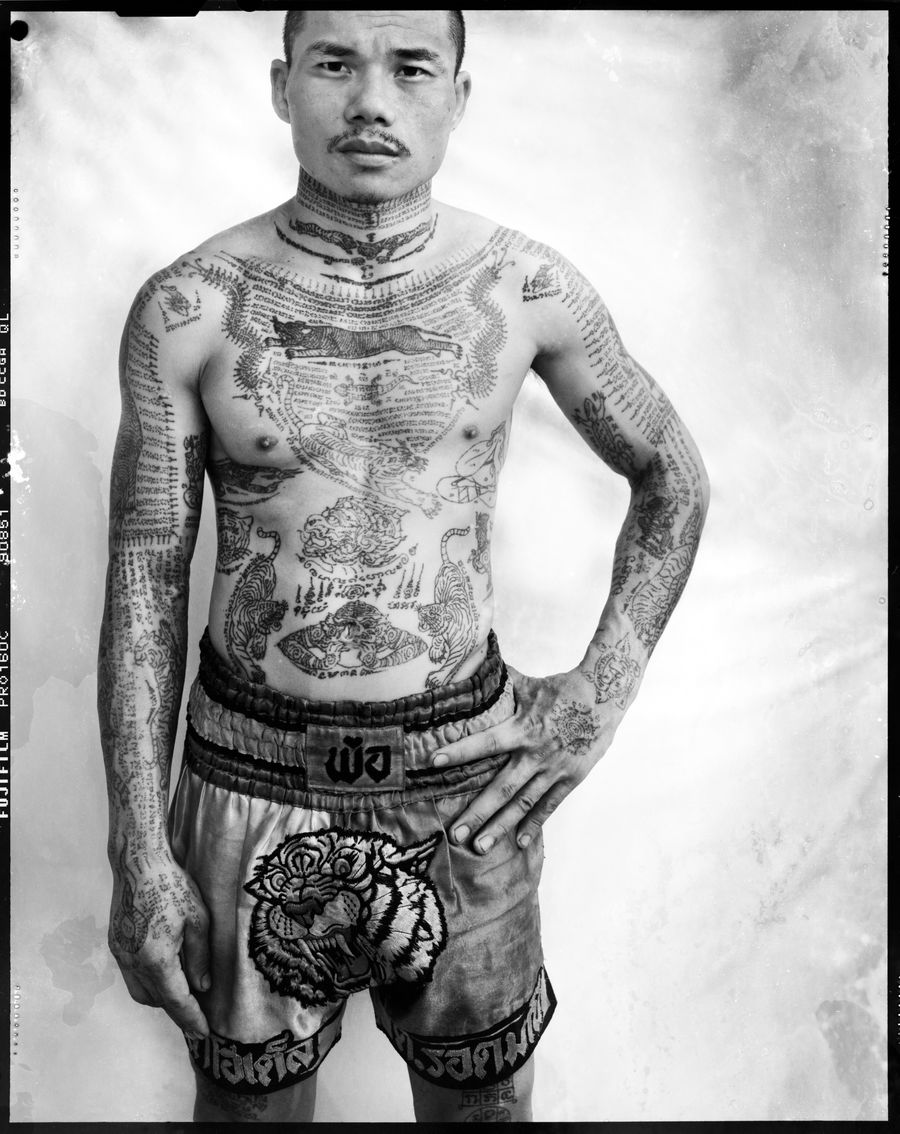

Yantra, Muay Thai boxer, Bangkok. Photography, montage on ‘kapa-board’, France, 2008-2011 © Photo: Cédric Arnold.

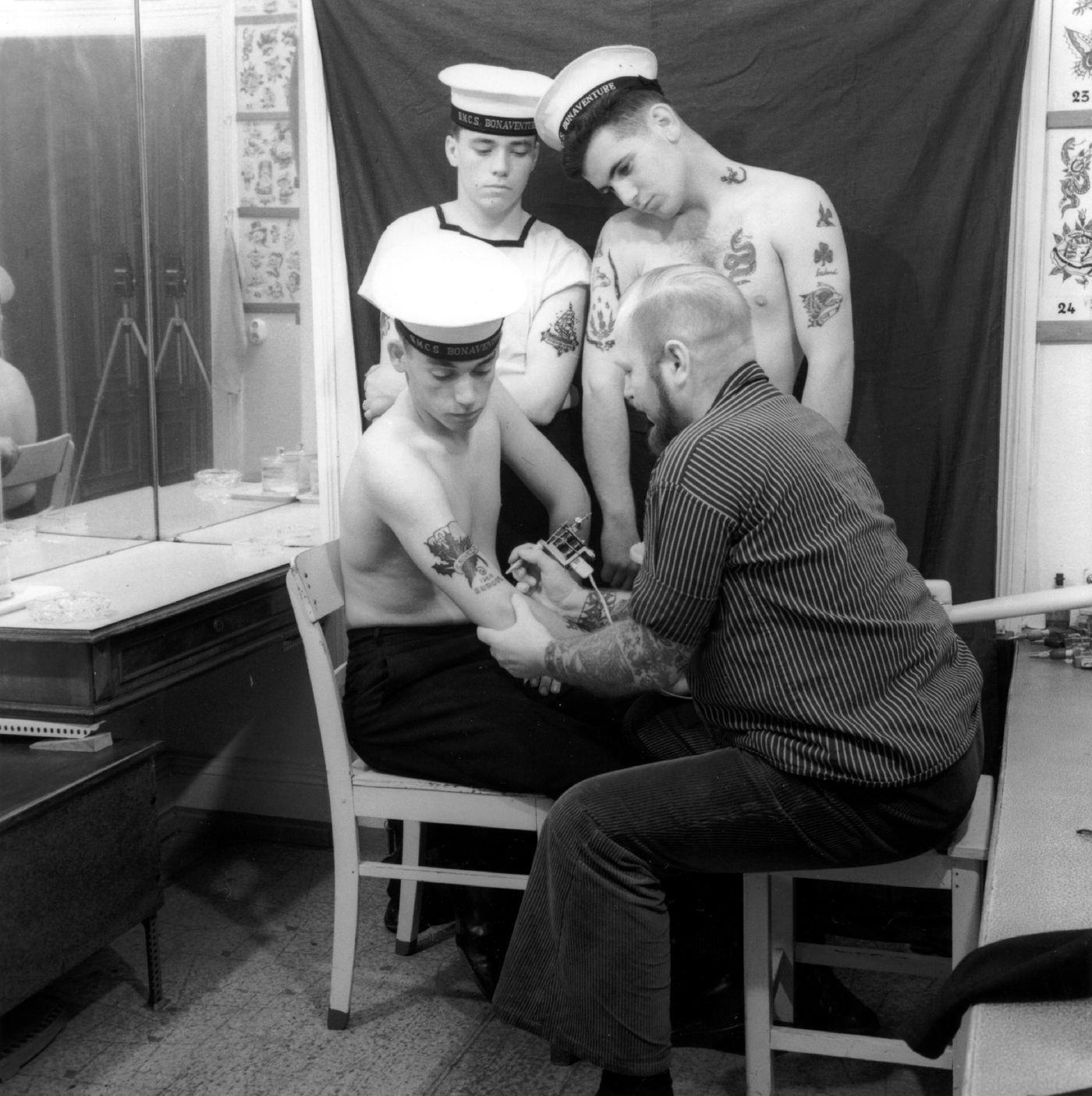

Flottenbesuch in Hamburg 1966. Photo: Schwarz-Weiß © Courtesy Herbert Hoffmann and Galerie Gebr. Lehmann Dresden/Berlin.

Although Pascal Bagot had already travelled around Asia and despite his growing fascination with Japanese tattoo art, he was reluctant to confront Japan right away which he explains: ''Japan had a mystery element to it, something to be revealed, which I was utterly drawn to. Although I had travelled around Southeast Asia, I didn’t want to explore Japan as a backpacker.''

This was all to change in 2006 when Bagot found the door that would take him right to the core of Japan as well as the age-old art form and went to Japan for the first time. ''I had fallen in love with Japanese tattoo art and decided that I wanted to be tattooed - that would be the context I had been looking for to learn about the country. I didn’t want to stay on the surface of Japanese culture; I wanted to try and go to the very heart of the country.''

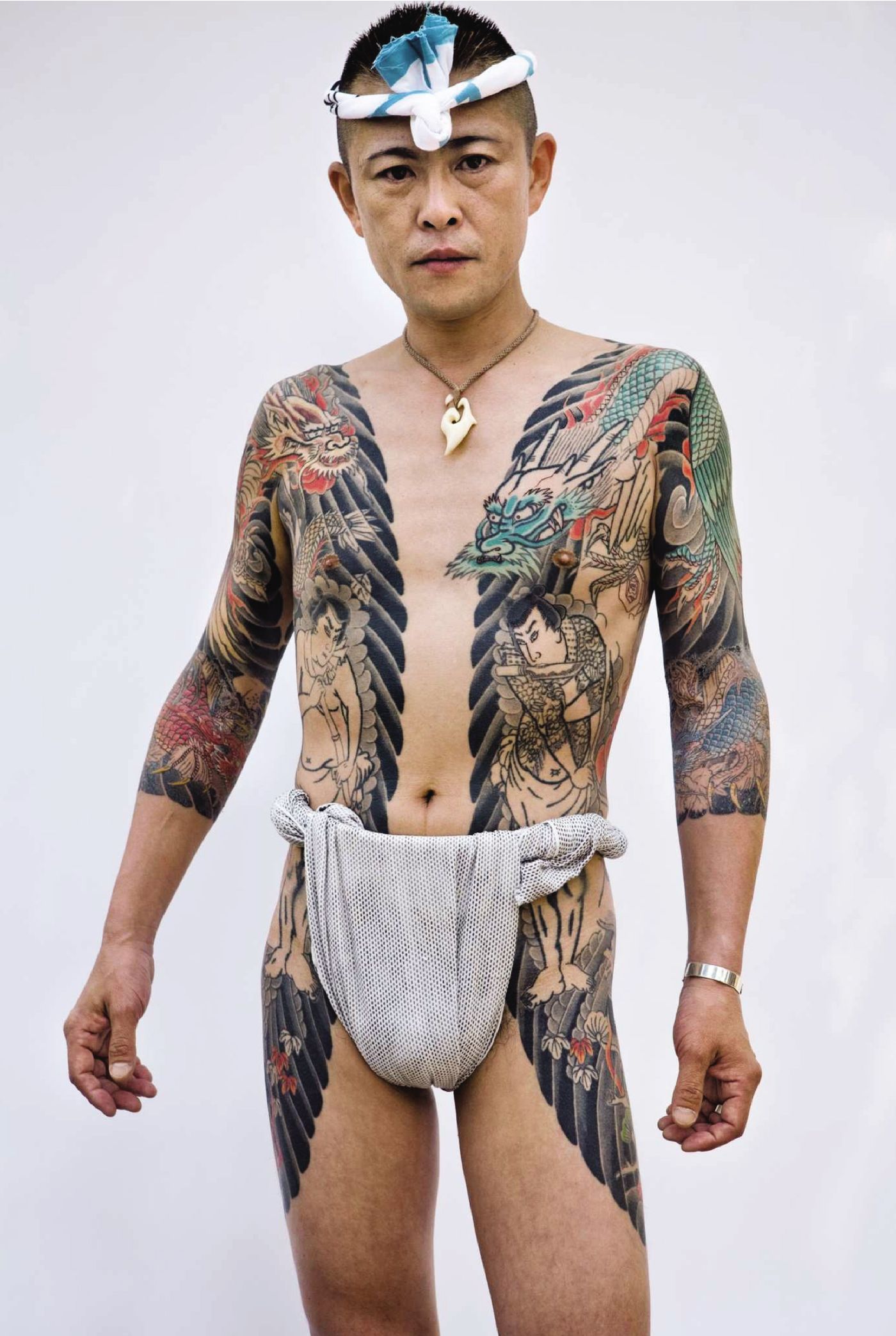

It was on his first trip that Bagot met Sensei (master) Horitoshi I. He had already decided that he would be the one to tattoo him. ''I loved his work and fortunately got on really well with him. I worked out that it would take about 8 years – and about 20,000 euro – to finish my tattoo, which is a dragon that covers my back. There was no doubt in my mind. As soon as I had the idea, I had to have it – it was an obsession.''

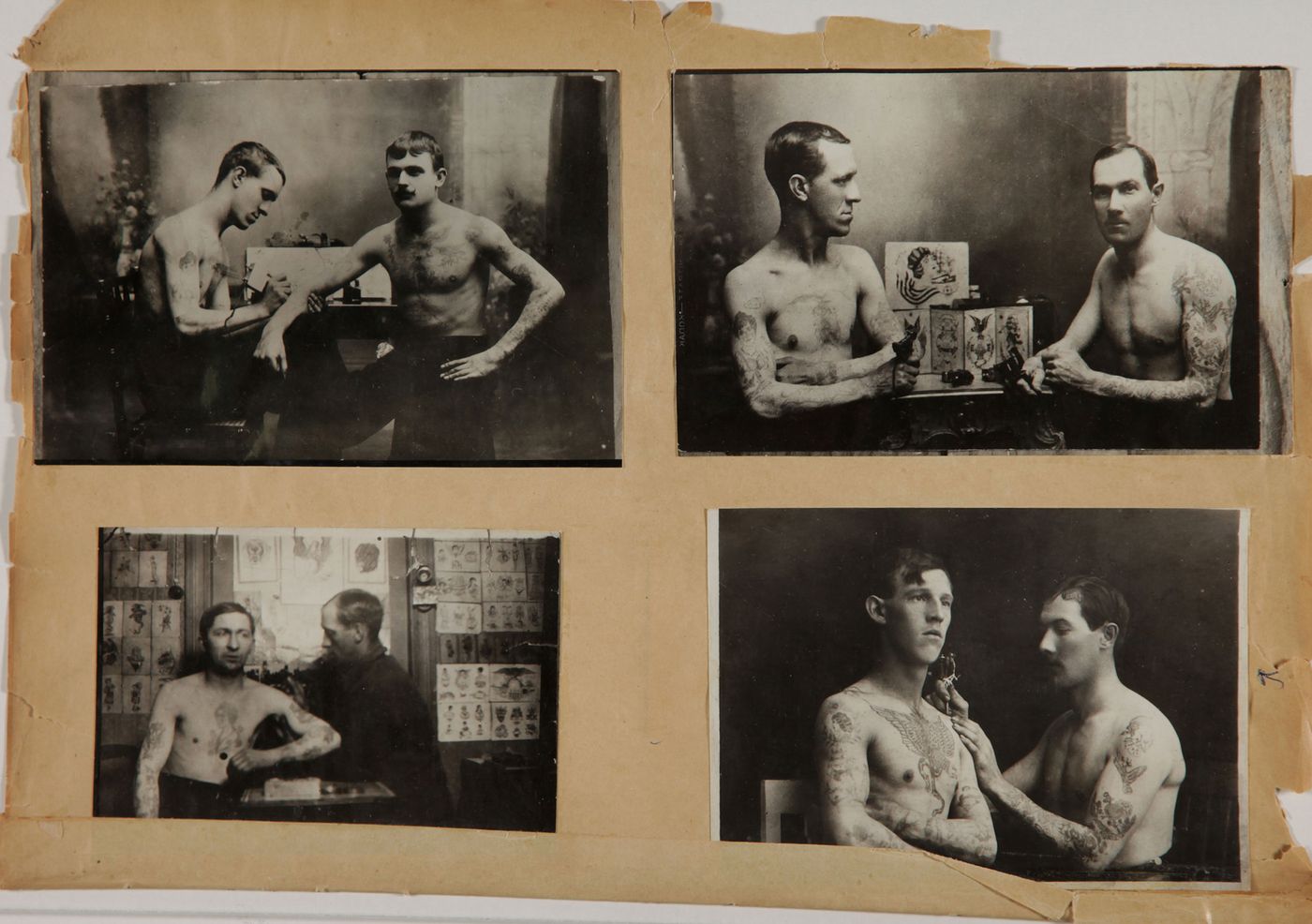

Images from the ‘Recueil Lacassagne’, 1920-1940 © Gdalessandro/ENSP.

Ever since, Bagot has travelled to Japan between one and three times a year, a total of 124 hours of work, to continue his tattoo with the Sensei which will be finished this year. ''I’m not sure if I’ll stop there. We’ll have to see. Because the beauty of traditional Japanese tattoo is that the Sensei envisions a continuation of the tattoo at every stage in case the client wants to come back and continue it. It can also be finished at any stage the client decides.''

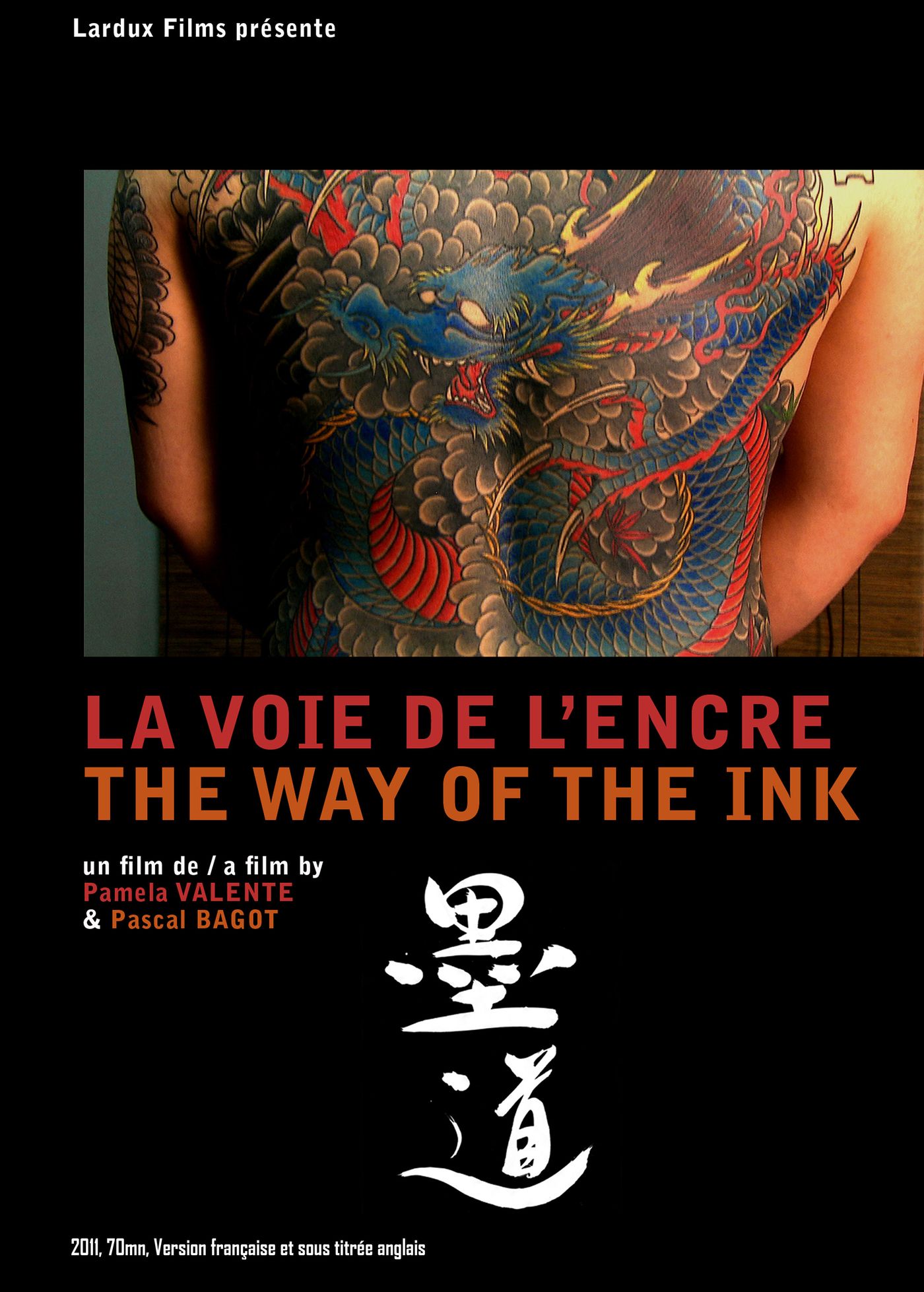

In 2010, Pascal Bagot went on to direct The Way of the Ink (La Voie de l’Encre), a behind-the-scenes documentary about Japanese tattoo art. ''I was completely flabbergasted by the magnitude of the work and culture behind traditional Japanese tattoo art. It was a real culture shock. For me, this documentary, along with the magazine articles I have written and the Tatoueurs, tatoués exhibition, are ways of shining light on this complex and extremely meticulous art form that is still very much dependent on secrecy and discretion – something that is basically almost impenetrable.''

Tryptic of Japanse prints: the dual. The prints represent two Kabuki theatre actors in a dual against a winter backdrop. Realised by Toyohara Kunichika (1835-1900). The actor on the right is Ichikawa Danjurô, in the rôle of Kumonryû Shishin, a mythical figure tattooed with nine dragons. The actor on the right is Ichikawa Sadanji in the role Kaoshyôrochishin, covered in a Kaidô flower tattoo representing the family of roses. Edo and beginning of Meiji periods, year 18 of the Meiji era, Japan © Musée du quai Branly, photo: Claude Germain.

Japanese tattoo, also called Irezumi, Horimono or Gaman, can cover the entire body, and is still heavily stigmatised as a result of its association with the tattoos worn by members of the Yakuza, or Japanese mafia. In fact, records of tribal Japanese tattoo go as far back as several thousand years B.C. and although the context of tattoo art has of course since changed, it still remains an expression of individuality, as Bagot explains: ''It wasn’t until the 19th century, during the cultural Edo period, that Japanese tattoo started to develop as an art. Before that, it was used primarily to mark prisoners and also developed in pleasure quarters of cities as a symbol of love between prostitutes and their clients.''

Extremely elaborate, both artistically and culturally, traditional Japanese tattoo also evolved with the popularity of Kabuki theatre and the very arduous and intricate work of Japanese print artists; over 70 prints will therefore be on a three-month rotation as part of the exhibition.

''Through Tatoueurs, Tatoués it was important for me to share the complexity of Japanese tattoo culture and how it has and is still evolving as an art form. Japanese tattoo art is still taboo in Japan, but if we want this art form to survive and if we want tattoo art to be more widely accepted as an art, it is important to document it and share its beauty. My personal hope is for the negative judgments associated with tattoos to be dispelled in Japan because it is simply magnificent in its complexity and so much more than just a Yakuza symbol.''